Systemic sclerosis breakthrough

20 September 2007

Links:

ucl.ac.uk/rheumatology-and-connective-tissue-diseases" target="_self">UCL Centre for Rheumatology & Connective Tissue Disease

ucl.ac.uk/rheumatology-and-connective-tissue-diseases" target="_self">UCL Centre for Rheumatology & Connective Tissue Disease

An international team of scientists and medics from the UK, Italy and Mexico, led by Professor David Abraham (UCL Centre for Rheumatology & Connective Tissue Disease), in close collaboration with the genetics group at the Brompton Hospital and Imperial College, led by Professors Ron du Bois and Ken Welsh, has identified the role of a genetic variant in the development of systemic sclerosis, a severely debilitating and life-threatening disease.

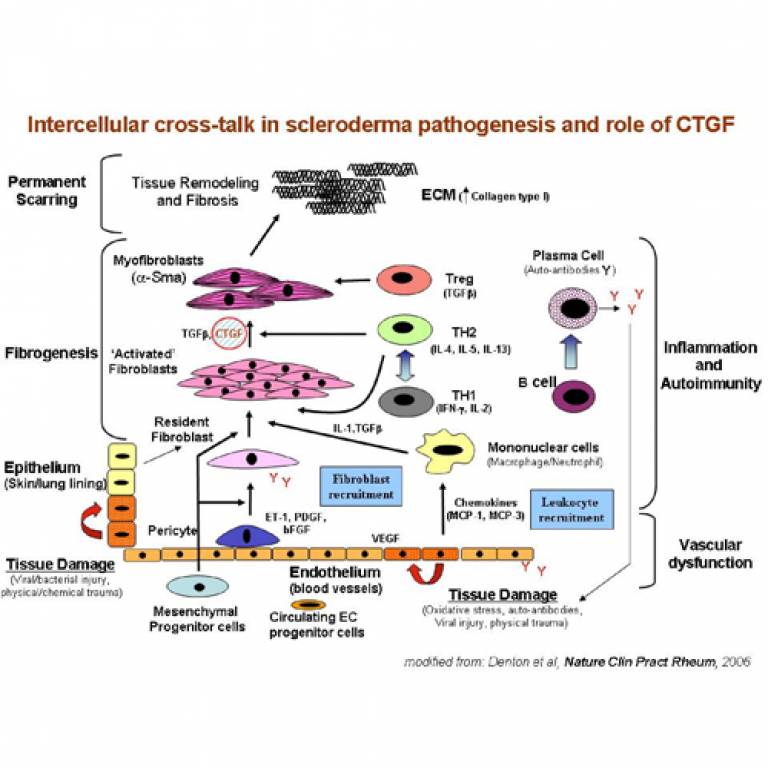

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) - also known as scleroderma - is an autoimmune rheumatic connective-tissue disease, which causes inflammation, fibrosis and hardening of the skin and internal tissues. It leads to stiffness, discomfort and often disfigurement as well as disabilities such as reduced joint and hand movement. In many patients, this process takes place within the major internal organs and tissues, including the heart, lungs, blood vessels and kidneys, leading to scarring and loss of normal function.

Despite collective worldwide research efforts in recent years, the cause of the disease has proven to be elusive, but is believed to be very complex combination of multiple genetic and environmental factors.

Professor Abraham's team focused on the connective tissue growth factor (CTGF), a protein that is already known to be involved in the process of wound healing and scarring. High levels of CTGF are found in patients with SSc.

The study, published in the 20 September 2007 issue of 'The New England Journal of Medicine', demonstrates for the first time that the presence of a genetic variant in CTGF is highly common in patients with SSc. It is even more common in certain sub-groups of patients with the disease who have lung fibrosis - the formation of scar-like tissue within the lungs - and those patients with a particular autoantibody in their blood - a protein produced by the immune system that is directed against the bodies own tissues.

Professor Abraham explained: "The discovery means that individuals with this gene variant are at much greater risk of developing SSc, particularly affecting the lungs. However, other factors - both genetic and environmental - are needed in combination with this for the disease to occur."

The findings also produce strong evidence of how this particular gene variant functions in relation to SSc. "The genetic variant is located with the promoter region of the CTGF gene, the regulatory region that controls the gene expression," said Professor Abraham. "The variant associated with SSc has lost the ability to bind a protein called Sp3, that influences the production of CTGF. This results in much higher levels of this scar-inducing factor being produced. It is believed that these higher levels of CTGF, under certain circumstances, contribute to the development of fibrosis in the connective tissue of SSc patients."

Professor Abraham concluded: "Our findings are consistent with reports of high levels of CTGF in a number of common human diseases characterised by excessive scarring and fibrosis, including liver cirrhosis, renal diseases associated with diabetes, heart and cardiovascular diseases and atherosclerosis. This study represents an important step forward in understanding the mechanisms underlying SSc and may also have implications for other fibrotic diseases."

The project was supported by the Arthritis Research Campaign, the Raynaud's and Scleroderma Association, the British Heart Foundation, the Asmarley Trust, the Scleroderma Society and the Weldon Foundation.

To find out more, use the links at the top of this article

Image: Diagram showing how injury or inflammation of endothelial cells can lead to production of collagen by fibroblasts. This can lead to systemic sclerosis (SSc) when the immune response is out of control

|

UCL Context Professor Abraham is Head of Laboratory at the UCL Centre for Rheumatology & Connective Tissue Disease. The centre focuses on connective tissue diseases, a spectrum of disorders with subsets that can be distinguished both clinically and serologically. The diseases generally evolve over a number of years, leading in the most severe forms to organ failure and death. It is estimated that around 80 million people in Europe, the United States and Japan are affected by these diseases. |

Close

Close