NEURObotics…the future of thinking?

17 October 2006

An exhibition at the Science Museum, featuring the work of several UCL researchers, shows how medical technology could boost our brains, read our thoughts and give us mind control over machines.

'NEURObotics…the future of thinking?' is an interactive exhibition that aims to stimulate debate about the ethics of using new powerful technologies, such as functional Magnetic Resonance Imaging (fMRI), to improve our brains.

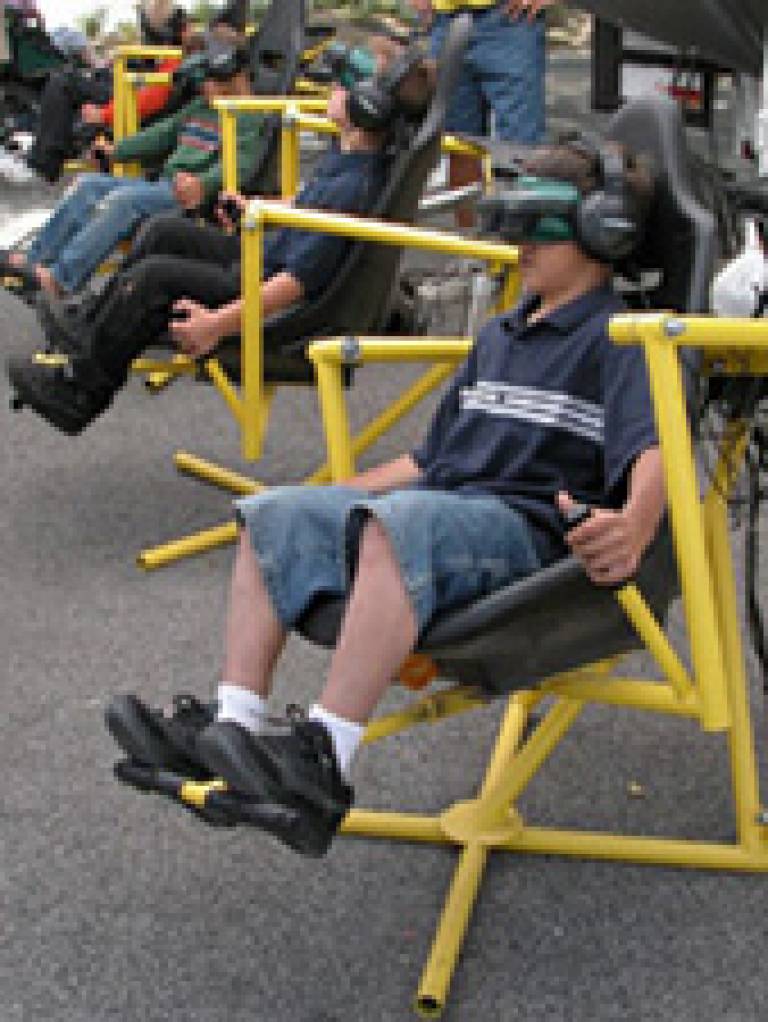

Dr David Swapp (UCL Computer Science) explains his virtual reality work, based in 'an immersive projection theatre' using 3D glasses that bring computer images projected on the walls and floor to life. His team envisages that brain-computer interfaces could replace the familiar joystick, allowing people to negotiate virtual worlds through their thoughts.

Dr Swapp is testing how realistic virtual reality can be by taking the pulse of people 'in' the virtual world to gauge their anxiety as different scenarios unfold. In addition to entertainment purposes, the technology is used by designers and architects to 'walk around' virtual new buildings before they have been built.

Professor Geraint Rees (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience) is showcasing his explorations of the difference between the conscious and unconscious mind.

Volunteers in his lab try to spot the differences in two near-identical pictures that flash before their eyes. By taking pictures of their brains processing the puzzle, Professor Rees maps the active areas of the brain while they search - and pinpoints when they consciously spot the difference. He also uses fMRI scans to distinguish which pictures volunteers can see, without having to ask them.

Professor John Rothwell (UCL Institute of Neurology) explained how stimulating the brain with a magnetic pulse (transcranial magnetic stimulation or TMS) can help stroke patients: "If you stimulate a part of the brain over and over again using TMS, you can change the connections between neurons - either strengthening or weakening them. This sort of thing happens naturally when you repeat a task over and over again to learn it - this is the basis of things like memory. TMS allows you to do it artificially."

He added: "Stroke patients may have damage to one pathway in their brain. If you can maximise an alternative pathway using TMS, you can help rehabilitate the patient."

Professor Vincent Walsh (UCL Institute of Cognitive Neuroscience) sounds a note of caution about claims that TMS could help to treat autism, but is more upbeat about its potential to alleviate depression. He believes that scientists and doctors often look for different success rates in their experiments, but if they can work together more closely, the outlook for TMS in depression may be more positive in the future.

'NEURObotics…the future of thinking?' is a free exhibition at the Science Museum, running until April 2007.

To find out more, use the links at the bottom of this article.

Image: Virtual reality games can be a group activity

Close

Close