Immaterial Architecture

23 November 2006

Professor Jonathan Hill's (UCL Bartlett) new book 'Immaterial Architecture' explores the history of the immaterial in architecture.

Arguing that the immaterial is as important as the material, Hill makes his case by exploring not only architectural production but the means of architectural production, and how the profession has evolved and developed through the years.

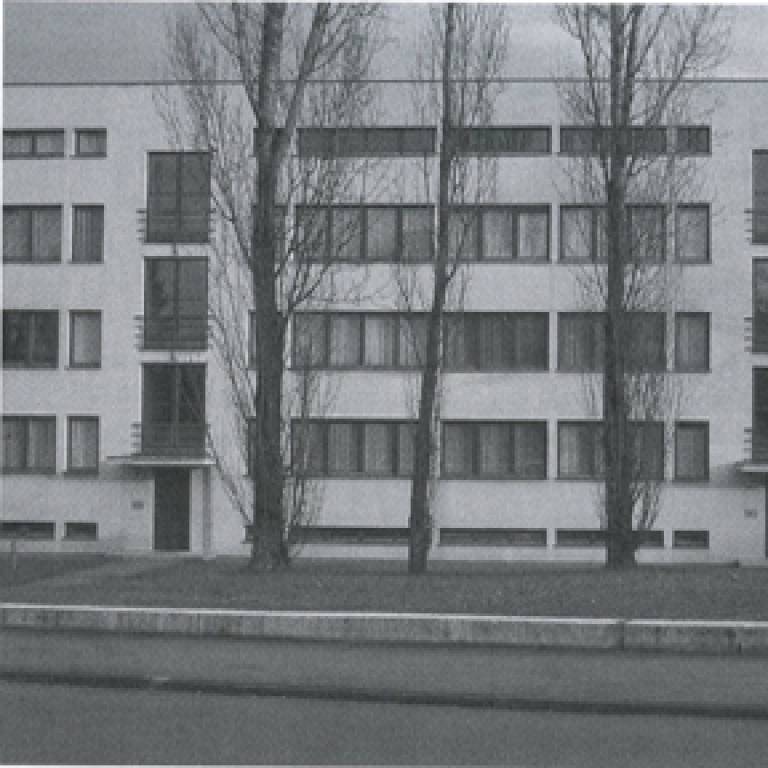

Arguing that the immaterial is as important as the material, Hill makes his case by exploring not only architectural production but the means of architectural production, and how the profession has evolved and developed through the years. Ever since Vitruvius wrote about the primitive hut in 25BC, architectural historians have viewed the house as the origin and archetype of architecture. This premise informs the first chapter of the book, which discusses whether or not the concept of home must necessarily be the embodiment of the material in architecture. Using examples from seventeenth-century domestic architecture and the modernism of Le Corbusier and Mies van der Rohe, Hill deconstructs the concepts of domesticity and functionalism with regard to the material and immaterial.

Hill is interested in the role of the architect and the pressures inherent in a profession which, by its very nature, tends to conceptualise buildings rather than build them, or rather, works in the immaterial rather than the material: "Sometimes a building is not the best means to explore architectural ideas. Consequently, architects, especially famous ones, tend to talk, write and draw a lot as well as build", explains Hill.

Hill traces this back to the fifteenth century, when the role of architect became recognised as a profession in itself: "From the fifteenth century to the twenty-first century the architect has made drawings, models and texts, not buildings." He continues: "As architects draw buildings and do not physically build them, the work of an architect is always at a remove from the actual process of building."

But what does immaterial architecture mean, and can we separate the immaterial from the material? "The user decides whether architecture is immaterial. But the architect, or any other architectural producer creates material conditions in which that decision can be made. In conclusion, Immaterial Architecture advocates an architecture that fuses the immaterial and the material, and considers its consequences, challenging preconceptions about architecture, its practice, purpose, matter and use."

Ultimately, Hill is interested in a hybrid: "My concern is not the immaterial alone or the immaterial in opposition to the material. Instead I advocate an architecture that embraces the immaterial and the material." To find out more about the book and Hill's research, use the links at the bottom of this article.

Image: Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, Weissenhof Siedlung, Stuttgart, 1927. Front elevation. Photograph, Jonathan Hill

Close

Close