Archaeology Turns Political to Benefit a Trio of Middle East Strongmen

15 October 2021

When it comes to the Middle East and its cultural heritage, the media is rife with reports of looting, illegal trafficking of artifacts, and on a more positive note, restitution, such as the return from the U.S. to Iraq in September 2021 of the 3,500-year-old Gilgamesh Tablet, with inscriptions in Sumerian. Going back 10 years to the Arab Spring and eight years before that to the invasion of Iraq, much of the region has experienced terrible loss not only on a human scale, but also of its archaeological heritage. The culmination of both came in 2015 with the brutal murder of the 82-year-old archaeologist Khaled al-Asaad — who had been in charge of the Syrian UNESCO World Heritage site of Palmyra for 40 years — and the destruction of part of the 2,000-year-old site by the Islamic State group.

“A Nation Stays Alive When Its Culture Stays Alive,” is the motto engraved in stone outside the National Museum of Afghanistan in Kabul. But in this simple sentence lies all the complexity of just how a nation sees itself.

Three countries — Iraq, Syria and Libya — have an extraordinary heritage of ancient archaeological sites, many of them now endangered, and had in common long-standing dictators, (although in the case of Syria, of course, the Assad regime continues), all of whom used their cultural heritage in various ways to define how they saw their nation.

That dictators draw inspiration from ancient history to shape their nations is nothing new — Mussolini looked back to the Roman empire, while Hitler and the Nazi party developed their mythical, ancient “Aryan” race. The last shah of Iran, Mohammad Reza Pahlavi, threw one of the most lavish parties in history at Persepolis in 1971 during national celebrations to illustrate the grandeur of the 2,500-year-old Persian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in the sixth century B.C.

Saddam Hussein, Hafez al-Assad and Moammar Gadhafi all came to power in the late 1960s and ’70s and governed respectively for 24, 29 and 42 years. They were all inspired by Pan-Arabism but developed their individual takes on it.

Both Saddam and Assad recognized the value of their countries’ archaeological heritage and adapted it to suit their interpretations of what they thought the Baath Socialist Party should be. They also both came from minorities — Saddam a Sunni Muslim in a country that was majority Shiite and Assad an Alawite in a mostly Sunni Muslim country. They both saw it necessary to unify people of different beliefs and used the landscape and a past encapsulated in archaeological sites.

In an essay in the Journal of Social Archaeology from 2008, Iranian archaeologist Kamyar Abdi quotes Saddam in a speech to Iraqi archaeologists shortly after he took power: “The Department of Antiquities is your responsibility and particularly the experts among you. It safeguards the antiquities which are the dearest relics the Iraqis have, and which show the world that our country which is today witnessing unusual revival is the [offspring] of the previous civilizations that have greatly contributed to mankind and set great landmarks for the whole mankind.”

In the years after the Baath party came to power, writes Abdi, the budget for the Department of Antiquities increased by 80% and the number of excavations mushroomed, as did the renovation and reconstruction of historical sites.

“Honestly speaking, it was better then than it is now,” said Iraqi archaeologist Haidar Almamori in an interview with New Lines Magazine, speaking from Babylon. Almamori is from the ancient city of Babylon and teaches at the University of Babylon. He also works as field director in the ancient city of Dilbat.

In Syria, too, Assad’s promotion of archaeology was, as the late journalist Patrick Seale described it, part of his exercise in nation building. Stéphane Valter, a French political scientist who specializes in Arab culture and civilization, studied Assad’s relationship to Syria’s archaeology in his 2002 book, “La construction nationale syrienne” (“The Syrian national construction”). He writes that because of the fragility of a social cohesion in Syria due to its varied ethnic and religious communities, it was important for Assad to establish a territorial and historical identity in which all minorities could find a legitimate place. The archaeological richness of Syria doubtless helped build a national identity based on a culture that was promoted as authentically Syrian.

Gadhafi’s relationship to Libya’s cultural heritage was quite different and a reflection of his “unstable personality,” according to Mohamed Ali Fakroun, who spoke from Tripoli. Fakroun had just finished his studies in 1986 when he began working in Libya’s Department of Antiquities. He recalls being at the inauguration of the National Museum of Tripoli in 1988 (where he eventually became one of its directors), when Gadhafi stopped by.

Gadhafi’s view of Libya’s heritage was selective, but like the other dictators, it aligned with the message he wanted to transmit.

“Libya links east to west, and north to south, and there are examples of all the cultures that were around us,” said Fakroun.

But Gadhafi largely favored Islamic archaeology, in keeping with his Pan-Arab ideological preference at the time (vis-a-vis Pan-Africanism, which he embraced in later years), and after that, prehistory because it was far enough into the past to be relatively uncontested. In contrast, British archaeologist Graeme Barker, who spent many years in Libya, explained that “the country’s fabulous Greek and Roman archaeology represented to him simply the precursor of the hated Italian colonization of the 20th century.”

On the day of the inauguration, when Gadhafi saw that the museum staff had named some of the rooms “Greek” or “Roman,” his face fell, said Fakroun, “and he made us change the names to ‘Greek colonization’ or ‘Byzantine colonization.’ ”

“We couldn’t talk about our Amazigh heritage. Or objects that were Tuareg, we had to say they were Arab. We wanted to be scientific, but we couldn’t, because the only ethnicity that existed for him was Arab,” said Fakroun.

In their essay, “Political Ruptures and the Cultural Heritage of Iraq,” forthcoming in Routledge’s “Handbook on Sustainable Heritage,” cultural advisers Rene Teijgeler and Mehiyar Kathem write that the Baath regime in Iraq sought to “connect modern-day Iraq with its glorious Mesopotamian past, leaving aside any possible Sunni-Shia division or ethnic divide. Instead, it stressed that Iraq was one nation unified in a shared Mesopotamian-inspired culture.”

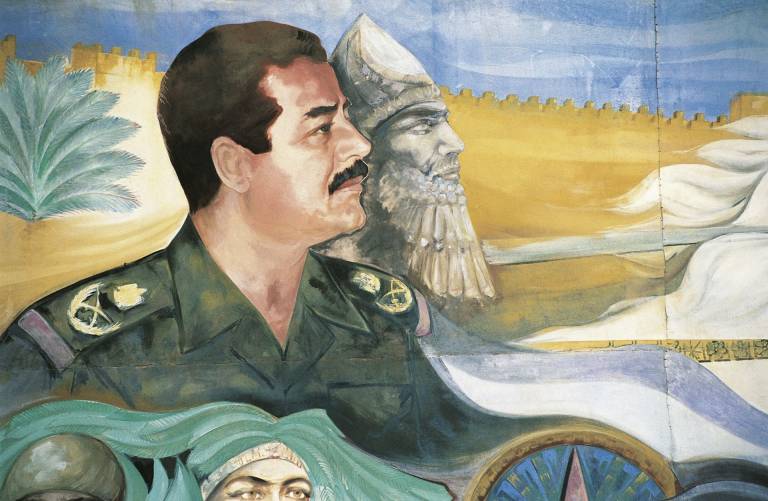

Saddam’s obsession with the Babylonian ruler and warrior Nebuchadnezzar II has been well documented. During his reign, Iraq was flooded with propaganda posters, murals and sculpted reliefs in the style of ancient artworks, all depicting Saddam superposed with Mesopotamian rulers or symbols. Ancient Babylon, therefore, became the focus of Saddam’s infatuation and an instrument to symbolize the ethnic unity of Iraqis. In the 1980s, Saddam chose to renovate Babylon, where Nebuchadnezzar’s Ishtar Gate in glazed yellow and blue bricks was first built. The original was removed in the early 20th century by German archaeologists and reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum in Berlin.

Saddam rebuilt the site shoddily, most professionals agree, and built a palace for himself on top of it. He used new materials and inscribed his name on the bricks, as Nebuchadnezzar had done over 2,000 years before him. Moreover, said Almamori, “he dug three or four lakes, which damaged and removed part of the Persian cemetery near the northern lake. Many layers of different civilizations were removed. He constructed artificial mounds and built his palace on one of them. Archaeologists with high positions were afraid to say anything.”

That said, Almamori suggests that what Saddam did wasn’t so strange when you consider that he copied what the ancient kings did by rebuilding their temples: “When Nebuchadnezzar II took over from his father, Nabopolassar, he ruled from the same palace which he rebuilt. The Baath party related to this — we have a long history, a strong civilization, that needs a strong army. Nationalists in other countries think the same way.”

In Syria, Valter describes how the Baath party in the 1970s founded a committee to rewrite history with a secular vision, with Islam simply as one expression of the Arab civilization. In this sense, the Umayyad period of history was useful to the party because of its multiethnic nature. The Umayyad Mosque in Damascus was one of the best symbols for the party, writes Valter, because of its specifically Syrian cultural traits — first an Aramean and then a Roman temple, then a church and finally a mosque. The mosque figured on Syria’s most valuable banknote at the time, behind an image of Assad. Banknotes included images of Aleppo’s Citadel, the Roman amphitheater of Bosra and Queen Zenobia of Palmyra, and clearly showed the regime’s wish to conflate ethnocultural Arab references with nationalist pride and a pinch of Islam, Valter writes. For Syria’s ancient sites, it was the same. They needed to be approved by the regime, their stories following Assad’s form of secular Arab nationalism.

Ali Othman, a Syrian archaeologist and heritage curator now based in Paris, explained there was a foreign policy element to the archaeological sites in Syria as well. Although the party’s historians had the upper hand in rewriting history, and the heads of the antiquities departments of the various sites were with the Baath party, the excavation of sites was most often left to foreign archaeologists, from France, Poland or Japan, for example. Othman added that the regime used its archaeological heritage “as diplomatic keys. Assad resolved his diplomatic issues with Europe and the U.S. by using culture as a bargaining point.”

According to Othman, the foreign archaeological community understood the politico-cultural stakes and played along because they loved working on the sites in Syria. Othman said that when he was a civil servant working for the Directorate of Antiquities, he was always afraid to visit the Palmyra site because he couldn’t get way from the fact that there was a terrible prison, Tadmor, just nearby. “Archaeologists acted as if the prison wasn’t there,” he said. Othman added that one of the most important ancient sites for Assad was Ugarit, near the Mediterranean city of Latakia. With five layers of cultures going back to the Neolithic period, not only is it famous for its clay tablets with an alphabet in cuneiform script, but Ugarit is also just north of Qardaha, where Assad was born and is buried.

Unlike in Saddam’s Iraq or Assad’s Syria, in Gadhafi’s Libya, the Department of Antiquities suffered from constant underfunding. “Our budget was next to nothing,” recalled Fakroun. “Once they forgot about the Department of Antiquities when they were drawing up the country’s budget. We had no salary for six months. We’re talking about a country with tons of money from petrol, and they gave us pennies. And we have five World Heritage sites.

“Like dictators everywhere, Gadhafi thought the country didn’t exist before him. We were lucky to have been educated before he came to power because all history lessons about ancient Libya were removed,” said Fakroun.

Fakroun remembers presenting a paper about a Christian mosaic at a conference on North Africa held in Paris. On his return, he was summoned to the security branch. “They showed me my paper and accused me of not mentioning the Jamahiriya [Libyan republic]. I told them I was talking about the fifth century.”

“In many ways,” said Barker, “the Department of Antiquities did an amazing job of heritage protection with these sites despite what could sometimes be called ‘malign neglect’ by the Gadhafi regime.”

A few years before Gadhafi’s downfall in 2011, his son Saif al-Islam had unveiled a $3 billion plan to renovate the country’s archaeological sites and develop ecotourism, but the project never got off the ground.

Over the past decades, outstanding archaeological sites in all three countries suffered looting, vandalism, neglect, or at the hands of the Islamic State or, in the case of Ancient Babylon, from U.S. and Polish troops building their military base on top of the ruins in 2003. A number of organizations are doing their best to help, such as the Heritage for Peace foundation, which works to protect cultural heritage in Syria and countries in conflict; the World Monuments Fund and the Nahrein Network in Iraq; or the French archaeological mission in Libya and the Society for Libyan Studies in the U.K.

The politicization of archaeology and its enlistment toward self-serving ends by nationalism and dictatorships is not lost on contemporary archaeologists.

Iraqi art historian and archaeologist Zainab Bahrani recently spoke on the podcast Afikra about why cultural heritage is valuable. In the episode, she makes a point of not referencing identity “because I’m very much against ethnonationalist identity and relationships to antiquities in that way.” Sure, architectural heritage anchors a place in history. But, she adds, “people become tied to historical architecture, people’s sense of self becomes tied to it, and you can see how, conversely, it can be used as a way of wiping out the memory of people.”

Close

Close