'Making sense of the cause of Crohn's - a new look at an old disease' - a review.

A team of scientists led by Professor Tony Segal of University College London has discovered the fundamental cause of Crohn's disease, a devastating, long-term bowel disorder that affects at least 115,000 of people in Britain and costs the NHS about £1 billion a year in treatment alone.

For decades, scientists have puzzled over why some people develop a chronic inflammation of the intestines for which there is no cure and that can lead to seriously debilitating symptoms with life-changing consequences for sufferers.

The inflammation caused by Crohn's disease can occur in any part of the alimentary tract, but most often in the walls of the intestines, such as the lower part of the small intestine (ileum) where it meets the large intestine (colon).

The first signs of the disease can appear in people at any age, but most commonly in their late teens and early twenties. The commonest symptoms include persistent diarrhoea, abdominal pain and cramping, extreme tiredness, weight loss and blood or mucus in the stools.

In some patients, Crohn's disease can also lead to systemic symptoms such as fever, nausea, pains in the joints, eye irritation, swollen skin and mouth ulcers. In the worst cases, Crohn's results in intestinal blockages and fistulas that require surgical intervention.

Although it is possible to treat the symptoms of Crohn's with drugs and in some cases surgery, there is no known cure. Even if patients feel better after therapy or an operation, they frequently relapse, making it difficult or impossible for many of them to continue leading normal lives.

The precise cause of Crohn's has been a mystery, although for many years it has been linked with certain risk factors such as a western lifestyle, smoking, migrating to foreign countries, gastrointestinal infections and genetic inheritance. Until now, no-one has been able to explain exactly what happens when the intestines appear to erupt spontaneously into a chronic inflammation that can persist, off and on, for the rest of a person's life.

Professor Segal's research has, however, shown that rather than being a disease caused by the over-activity of the body's immune system - the widely accepted view of Crohn's - it is actually the reverse, at least in its earliest stages.

His counter-intuitive findings suggest that Crohn's is actually caused by the failure of the "innate" part of the immune system. This is the part of the immune defences that protect the body against gastrointestinal infections in the critical first few hours [or days?] when harmful bacteria or viruses penetrate the gut wall during gastrointestinal infections.

It is this failure of innate immunity that causes long-term changes in the "adaptive" immune system, resulting in the chronic inflammation of the gut wall that is so typical of Crohn's disease. The adaptive immune response involves the long-term release of the messenger molecules and antibodies that are the hallmark of this chronic, inflammatory disease.

The discovery, which is the culmination of more than 40 years work, could now lead to a new understanding of why certain people are prone to developing Crohn's disease. It may also open the way for a gene therapy approach that might actually lead to a much-needed cure for the root cause of the disease rather than treatments that merely tackle the symptoms, Professor Segal said.

"We have found that the cause of Crohn's is a failure of the innate part of the immune system which is responsible for protecting the body immediately it comes under attack," Professor Segal said.

"This is counter-intuitive to how Crohn's disease is normally viewed and treated. Until now, it has been seen as an inflammatory disease caused by an over-active immune system.

"On the contrary, we have found the reverse. So rather than suppressing the immune system, which is how current drugs work, we should be thinking of stimulating it - or at least that bit of it that we now know to be deficient," he said.

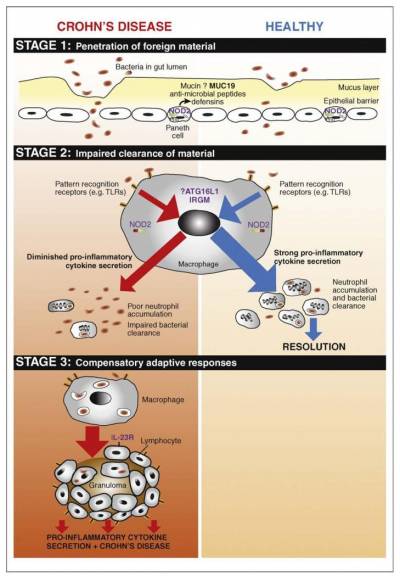

Professor Segal has proposed that Crohn's disease develops as part of a three-stage process:

From: Sewell GW1, Marks DJ, Segal AWCurr Opin Immunol. 2009 Oct;21(5):506-13.

- Bacteria present in the intestine penetrate the gut wall during a gastro-intestinal infection brought on for example by food poisoning. This attack on the gut wall can potentially cause an internal leakage of faecal matter through the protective layers of the gut wall.

- The innate immune system launches an attack. This is led by macrophage cells secreting cytokine messenger molecules to stimulate or "recruit" another kind of white blood cell, the neutrophils, which are supposed to engulf and clear away the invading bacteria.

However, in people predisposed to Crohn's disease, stage 2 does not work effectively. The macrophages don't release the cytokines needed to stimulate the neutrophils; the neutrophils fail to accumulate in sufficient numbers; and the bacteria and faecal matter persist in the gut wall causing a long-term, persistent "adaptive" immune response - Crohn's disease.

"In many respects, Crohn's disease is a disease of the macrophages. Genes can predispose people and a gastrointestinal infection can act as the trigger for Crohn's. But there are several other environmental factors - such as smoking or moving to another country - that can raise people's risk of developing the condition," Professor Segal explained.

"However, the real cause of Crohn's is a failure of the innate immune system, specifically the ability of macrophage cells to recruit neutrophils when the gut wall is breached by invading pathogens. This impairment results in the persistent presence of faecal matter in the gut wall, causing granulomas or collections of immune cells that result in long-term, chronic inflammation," he said.

Genetic studies, including those on two extended families from the community of Ashkenazi Jews where Crohn's disease is three or four times more common than the general population, have revealed that certain genes may be responsible for an inherited predisposition to the disorder.

Professor Segal believes that a revolutionary gene-editing technique known as Crispr-Cas9 could in future be used to repair a patient's defective macrophage genes by gene therapy. This could be done by taking the macrophages from a patient's bone marrow, gene-editing them in the laboratory and then injecting them back into the patient.

"Advances in gene editing with Crispr-Cas9 technology make the corrective treatment of Crohn's disease a real possibility in the relatively near future," Professor Segal said.

"Once a primary causal mutation has been identified, and validated in animal models, bone marrow could be extracted, edited and reinfused into a conditioned patient in much the same way as it is applied during the gene therapy to treat primary immune-deficiencies," he explained.

A major review of the causes of Crohn's disease by Professor Segal is published in 17 October 2016 issue of F1000Research.

Further Reading:

Ref: F1000 Research; "Making sense of the cause of Crohn's - a new look at an old disease" https://f1000research.com/articles/5-2510/v1

Close

Close