Families and Food in Hard Times: European comparative research

The unequal distribution of entitlement and access to food is increasingly a feature of wealthy western societies, arising in the context of global crises and governmental policy.

1 June 2021

As Families and Food in Hard Times: European Comparative Research testifies, such crises most affect those with least resources. In this book we focus on the aftermath of the 2008 financial crisis and its effects on the food practices of children aged 11-15 years and their parents in low-income families.

Funded by the European Research Council, the research was carried out in the UK, Portugal and Norway. Using a mix of methods, including secondary analysis of large-scale datasets and qualitative research with 133 low-income families living in or near the capital cities of the three countries, we examined parents’ and children’s experiences of food poverty within the material realities of their households, localities and nation states.

Findings

In the UK and Portugal, poverty and food poverty are a result of low pay and low social security benefits, compounded by governments’ austerity measures that hit the poorest families hardest. Although Norway was less affected by the financial crisis and its benefits are more generous than those of the UK and Portugal, entitlement is firmly tied to employment in a high skills economy. Given the skills of migrants in Norway are often poorly matched to labour market demands, migrants are at much greater risk of poverty than other groups.

Our analysis of the EU Statistics on Income and Living Conditions survey found that low-income lone parents were more likely to experience food poverty than those families headed by couples and that, in the UK, the gap was widest by far. Comparing families’ food expenditure to national budget standards in the quantitative and qualitative research, we found that almost all low-income families were spending less on food than is customary for the average family of a similar type and size.

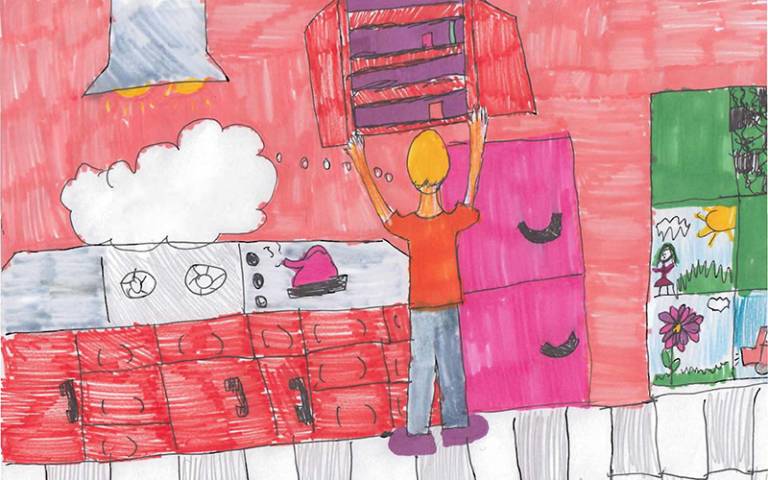

The fridge contents in the home of ‘Angela’, a lone mother with two teenage children living in a British coastal town, the day before she received her Jobseekers Allowance. She typically has between £20-£70 per week to spend on food.

Our qualitative research found that mothers, almost always the ‘food managers’, fed their families on highly constrained budgets. Some went to food banks, but all shopped around in different supermarkets and locations in search of bargains. Because most relied on public transport, this was expensive as well as time-consuming. Many lacked the money to bulk buy food and so lived hand to mouth. Those who could afford it used freezers as a cheap way of managing limited food resources. In Norway, most migrant families reported making monthly trips to Sweden to access affordable food. Many mothers cooked from basic ingredients and bulked out meals with cheap carbohydrate foods. Some lacked basic cooking facilities, like working ovens or electricity.

Mothers everywhere sought to protect their children from the worst direct effects of food poverty by cutting back on their own food intake and were often reluctant to admit their children were going without adequate food. Still, children in about one quarter of the families in each country mentioned going without enough to eat at times. A majority reported fruit or vegetable consumption below the national average. For their part, children moderated their needs and helped their parents by cooking or hunting for bargains. But they also mentioned difficulties in concentrating at school, being excluded from social activities and feeling different from their peers. Particularly in the highly unequal and consumerised UK, children mentioned being embarrassed by poverty and frustrated about the injustices of social inequality.

In all three countries, maintaining dignity and avoiding shame deterred mothers seeking help. In Norway, seeking discretionary support from the municipality was a norm for low-income families, although it typically involved a lot of red tape. In Portugal, families relied on family and friends, both routinely and in crises. In term time, their children participated in a three-course school lunch that was subsidised by the state, a provision that mitigated some of the food shortages at home.

In the UK, families more often turned to friends or were referred to formal support such as debt counsellors. Unlike in Portugal, many children did not qualify for free school meals (FSMs), which are means-tested and exclude most children whose parents are in low-paid work. Even if eligible, some children said the allowance did not stretch to a decent meal. Furthermore, children whose parents’ migration status meant they had No Recourse to Public Funds were not entitled to FSMs and went hungry, unless schools met the cost from discretionary funds. School holidays when there were no school lunches were times of worry and food shortage for families in the UK and Portugal. In Norway, where there are no school meals, the situation was reversed, with parents struggling to afford the customary packed lunch during term time.

Recommendations

In spite of the efforts of charities, in-kind food ‘solutions’ only conserve the status quo. The wider causes of poverty must be addressed. As the Archbishop of Canterbury, Justin Welby, put it, people are not ‘a ragbag of different physical needs to be met by a patchwork of largely volunteer organisations’, but ‘distinct human beings of infinite value’.

We recommend three immediate steps for governments:

- The International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) includes the Right to Food: ‘when every man, woman or child, alone or in community with others have physical and economic access at all times to adequate food or the means for its procurement’. While the UK, Portugal and Norway have ratified the ICESCR, they need to demonstrate how their national laws respect, reflect and enforce its obligations.

- Governments should use budget standards research to ensure both wages and benefits enable families to afford diets that meet their needs for health and social participation.

- Healthy school meals should be a universal resource like education and provided free at the point of delivery for all children in compulsory schooling.

Close

Close