Vasculitis means ‘inflammation of the blood vessels’.

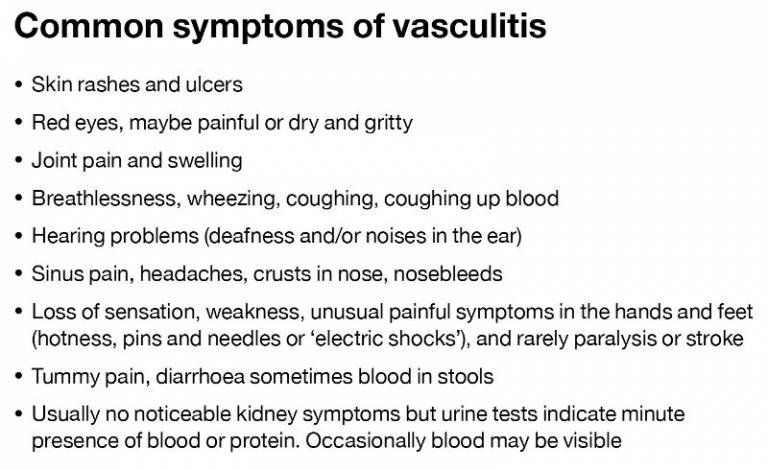

It leads to a varitety of conditions which can affect any organ. Most commonly kidneys, lungs, skin and joints are affected.

Vasculitis is an autoimmune disease, which means your immune system (which normally serves to protect us from infections and cancers) attacks the blood vessels by mistake. Individual vasculitis cases are rare, but taken together they affect thousands of patients in the UK. Currently there are no cures for vasculitis, but the diseases can be controlled.

Vasculitis may be secondary to provoking factors, most commonly an infection (e.g. hepatitis), or certain drugs (recreational or prescribed). Or it may be primary form for autoimmune diseases caused by a faulty immune system.

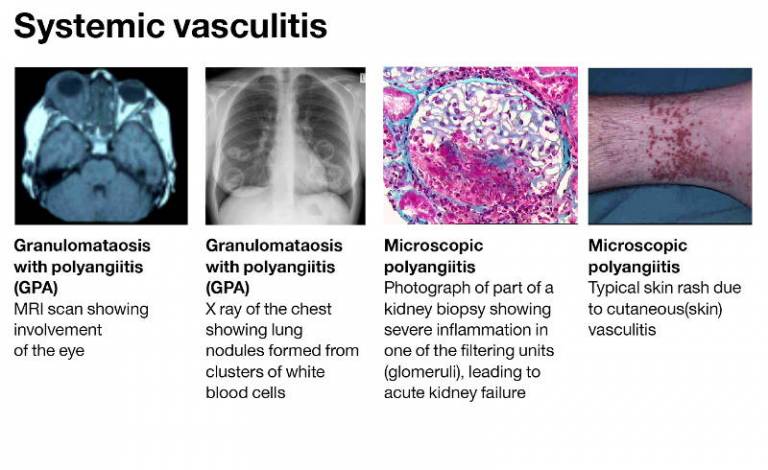

Systemic vasculitis diseases affect many organs. They have periods of activity and remission. The diseases can cause significant harm, both acutely when they first manifest themselves and long term in the form of chronic organ damage.

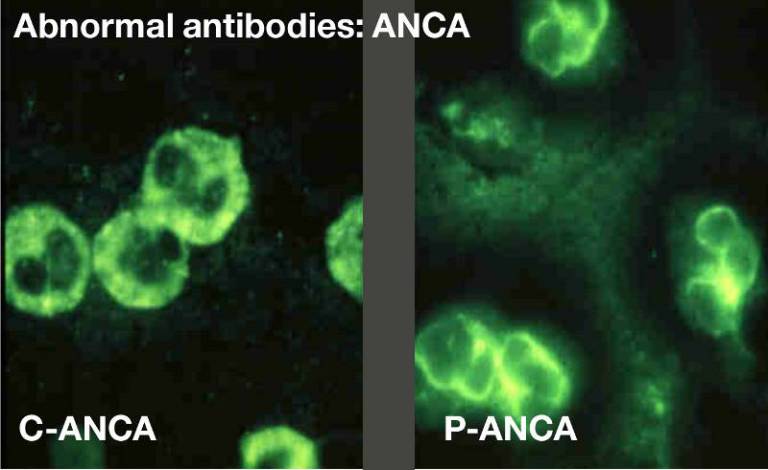

Systemic vasculitis may be associated with abnormal antibodies, such as ANCA. Levels of these antibodies are measured by blood tests which help decide on treatment decisions. The image shows different types of ANCA, called p-ANCA (or MPO-ANCA) an c-ANCA (or PR3-ANCA), identified by their staining pattern. Different ANCA types are associated with different disease patterns.

Treatment for vasculitis generally involves long term drugs called immunosuppressants, which are tailored to each individual's needs. Understanding how best to manage and improve these drug treatments is what vasculitis experts spend their time working on.

Genetic risk factors have been identified for many vasculitic syndromes, but a second factor is usually required to provoke the disease, often in the form of an infection. Rarely, vasculitis can run in families.

Future directions: improving the way we use our current medicines for treatment; individualising the way we treat patients; predicting who is more or less likely to relapse so that treatment can be tailored to them; and developing new ways of switching off the disease on a more permanent basis.

Close

Close