Financial Engineering Will Not Stabilize an Unstable Eurozone

6 April 2018

A number of economists and officials have recently proposed different schemes aimed at using financial markets to impose the right amount of discipline in the euro area. Paul De Grauwe and Yuemei Ji argue that this would not eliminate the inherent instability of the sovereign bond markets in a monetary union.

One thing we have learned from the financial crisis is that financial markets cannot be trusted as a disciplining device. During the booming years prior to the crisis, euphoria dominated in financial markets leading consumers, banks, firms, and investors to be blind for risk (Kindleberger 1978, Minsky 1986). As a result, encouraged by equally euphoric rating agencies, they took up massive amounts of debt disregarding the risks they took on their balance sheets. This was the time financial markets considered Greek sovereign bonds to exhibit the same risk as German sovereign bonds. Financial markets were an engine of indiscipline.

When the crash came, financial markets panicked. Suddenly they detected risks everywhere forcing consumers, firms and governments into excessive austerity, thereby deepening the recession (De Grauwe and Ji 2013). Financial markets became engines of excessive discipline.

All this is not new. Those who are interested in economic history and read deceased economists (Kindleberger 1978, Minsky 1986) have known for some time that financial markets almost never apply the right amount of discipline (see also Lo 2012). During booms markets apply too little discipline, thereby amplifying the boom, and during recessions they impose too much discipline, thereby making the downturn worse.

It is therefore surprising that a number of economists and officials have recently proposed different schemes aiming at using financial markets to impose the right amount of discipline in the Eurozone. A group of French and German economists have proposed various schemes such as sovereign bankruptcy procedures and triggers that would force governments to issue different tranches of debt in the hope of garnering the disciplining powers of the markets (Bénassy-Quéré et al. 2018, Lane and Langfield 2018). The European Systemic Risk Board (2018) published a report containing a proposal to create a "safe asset" for the Eurozone that is based on a repackaging of the risks of sovereign bonds. The hope is that this financial engineering will stabilize an otherwise unstable system of sovereign bond markets in the Eurozone.

We discuss these two proposals and analyze whether the financial engineering that is implicit in these will help to stabilize the Eurozone. We will argue that financial engineering cannot stabilize a financial system that is fundamentally unstable.

Let us first describe the nature of the instability of the government bond markets in a monetary union (see De Grauwe 2011, and De Grauwe and Ji 2013). We then analyze whether these proposals will succeed in stabilizing government bond markets in the Eurozone.

The instability of the sovereign bond markets in the Eurozone can be described as follows. National governments in a monetary union issue debt in a currency that is not their own, but is equivalent to a foreign currency. As a result of this lack of control over the currency in which the bonds are issued, these governments cannot guarantee that the bondholders will always be paid out at maturity. This contrasts with governments of countries issuing their own currency. These governments can give a full guarantee to the bondholders because they know that the central bank stands ready to provide liquidity in times of crisis. All this leads to a situation in which government bond markets in a monetary union can be hit by self-fulfilling crises: investors distrusting the capacity (or willingness) of a government to continue to service its debt, sell the bonds thereby raising the yields and making it more difficult for that government to rollover its debt. A liquidity crisis erupts which results from a fear that the government will be hit by a liquidity crisis. This usually happens during recessions when budget deficits and government debts increase automatically. Investors will then single out those governments perceived to be most at risk, sell their bonds, and acquire bonds issued by governments perceived to be less risky. As a result, massive capital flows across the borders of the monetary union are set in motion destabilizing the whole system. This is exactly what happened during the sovereign debt crisis of 2010-12.

The instability of the government bond markets in a monetary union is aggravated by a possible doom loop between the banks and the sovereign. When banks are in trouble, the sovereign who is obliged to save the banks will also be hit by a liquidity and possibly a solvency crisis. This was the problem of Ireland. The reverse can also happen: a sovereign debt crisis leads domestic banks, holding large amounts of domestic sovereign bonds, into illiquidity and insolvency (the Greek problem). The doom loop amplifies a sovereign debt crisis. That does not mean though that sovereign debt crises and the ensuing destabilizing capital flows cannot erupt in the absence of a banking crisis.

Let us now turn to the two proposals mentioned earlier.

1. The French-German reform proposals

There is much of intellectual value in the French-German reform proposals with which we agree (e.g. the proposals of completing the banking union and of creating some fiscal space at the Eurozone level). Here we concentrate on two proposals that aim at enforcing market discipline by financial engineering.[1] The first one proposes to change the existing structural budget balance rule by an expenditure rule that, if exceeded, would force governments to issue junior debt. The second proposal wants to enforce sovereign debt default procedures on governments that have become insolvent. Let us discuss these consecutively.

The idea behind the proposal to force governments to issue junior debt if their expenditures exceed some threshold value is that this will subject governments to more market discipline. The reasoning is the following. When governments spend too much they are forced to finance the extra spending by issuing junior bonds. As a result, the buyers of these bonds will face more risk and demand a risk premium. Thus these governments will pay a higher interest rate which will enforce more discipline. The market will do its job of raining in the tendency of governments to spend too much.

All this sounds plausible. The evidence of past financial cycles of booms and busts, however, is that this disciplining mechanism typically fails. During booms, euphoria prevails and few investors perceive risks. As mentioned earlier, during the Eurozone boom years, investor saw no difference in risks between Greek and German sovereign bonds. It is likely that when euphoria prevails they will see no significant difference in risks between the different tranches of outstanding government bonds.

During the downturn exactly the opposite will happen. In fact the existence of junior bonds will work as wake-up call and set in motion panic reactions of flight. As a result, governments, which have issued junior bonds, are more likely to be hit by a self-fulfilling liquidity crisis forcing them into excessive discipline and austerity.

The reality is that financial markets are not well-equipped to enforce discipline on sovereigns. The introduction of some new financial instrument will not change that reality. (It should be noted that the French-German reforms proposals also includes a proposal to create a safe asset. Wee discuss this separately in section 2).

The second proposal of the French and German economists aims at instituting a formal sovereign debt restructuring procedure. As these economists argue, governments that are insolvent should be forced to restructure their debt. In other words the holders of these governments' bonds should be forced to accept losses. As a result, investors would realize that, without a possible bailout of the sovereign, their investments would be risky. This would lead them to ask for a risk premium, thereby introducing market discipline on the behavior of the sovereign.

Again, at first sight this sounds reasonable. The same criticism, however, applies here to the one we leveled against the forced issue of junior bonds. There is very little evidence that investors ask for risk premia during boom phases. That's when euphoria blinds them in not seeing risks properly. And during the bust phase the opposite occurs. That's when the knowledge of the existence of debt restructuring procedures will act as triggers that create fear and panic. As a result, the existence of a sovereign restructuring procedure may actually trigger crises more easily during the bust.

There is an additional problem with this proposal. This has to do with identifying when governments are insolvent. It is easy to say that an insolvent sovereign should be forced to restructure his debt. It is much more difficult, during crises moments, to distinguish between solvency and liquidity problems. This difficulty arose during the sovereign debt crisis of 2010-12. In the case of Greece it was relatively easy to conclude that the Greek government was insolvent. But what about countries like Ireland, Spain, and Portugal? These countries were gripped by massive sales of their sovereign bonds leading to a liquidity crunch that made it impossible to rollover their debt at normal market conditions. Quite a lot of economists concluded that these countries were insolvent and should restructure their debt. It turned out that this advice was wrong and that these countries were solvent but had become illiquid. Had they been forced to restructure their debt, economic recovery would have been much more difficult.

2. The safe asset proposal

The proposal to create a safe asset in the Eurozone which was made by the ESRB explicitly aims at eliminating the destabilizing capital flows across the borders of the monetary union and to stabilize the system. Will it do this? This is the question we now turn to.

In contrast with earlier proposals to create Eurobonds (see De Grauwe and Moesen 2009, and Delpla and von Weizsäcker 2010) which assume that participating governments are jointly liable for the service of the national debts, the "safe asset" proposal makes no assumption of joint liability. Instead, in this proposal national governments are individually liable for their own debt. There is no pooling of risks.

The "safe asset" is created when financial institutions (private or public) buy a portfolio of national government bonds (in the primary or in the secondary markets) and use this portfolio as a backing for their own issue of bonds, called "sovereign bond backed securities" (SBBS). The latter have the following characteristics. One tranche, the junior tranche, is risky. When losses are posted on the underlying portfolio of government bonds the junior tranche takes the hit.[2] The second tranche, the senior tranche, is safe. The proponents of these SBBSs take the view that a 30% junior tranche is large enough as a buffer to take potential losses on the underlying sovereign bonds so as to make the senior tranche (70%) risk free. Based on simulations of underlying risk patterns, the authors claim that their proposal will allow to more than double the size of safe assets in the Eurozone. In addition, they claim that the existence of SBBSs will replace the destabilizing capital flows across national borders in the Eurozone by a movement from the risky asset (the junior tranche) into the safe asset (the senior tranche), thereby eliminating the instability in the Eurozone.

How likely is it that these SBBSs will help to stabilize the Eurozone? Note that in the way we formulate the question we do not dispute that in normal times the creation of a safe asset may not increase the efficiency of the financial system in the Eurozone. It probably will do so by supplying a new type of asset that can provide for a better diversification of normal risks. The issue is whether the safe asset will be an instrument for dealing with systemic risks in times of crisis? Our answer is negative for the following reasons.

First, the creation of a safe asset does not eliminate the national government bond markets. This is recognized by the proponents of a safe asset (see ESRB 2018 and Brunnermeier et al. 2016). In fact these proponents have made the continuing existence of national sovereign bond markets a key component of their proposal. According to the ESRB "the SBBS issuance requires price formation in sovereign bond markets to continue to be efficient" (p.33). The markets for sovereign bonds must remain large enough so as to maintain their liquidity. That is also why the ESRB proposes to limit the total SBBS issuance to at most 33% of the total outstanding stock of sovereign bonds.

This constraint on the issue of SSBS implies that national sovereign bond markets will be "alive and kicking". As a result, the major problem that we identified earlier, i.e. the potential for destabilizing capital flows across the borders of the monetary union will still be present. However, since the markets of sovereign bonds will have shrunk the yields are likely to be more volatile during crisis periods.

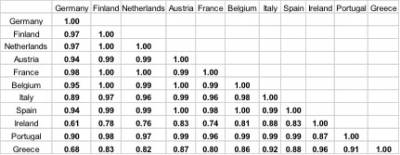

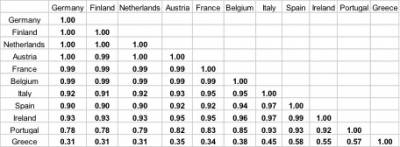

Second, we observe that during crises, the correlation pattern of yields changes dramatically. During normal times all yields are highly positively correlated. During crisis times, as investors are looking for safe havens, the yields in the safe assets tend to decline sharply and become negatively correlated with the high risk yields. This pattern was very pronounced during the sovereign debt crisis of 2010-12. In their simulations of the risks involved in SBBSs, Brunnermeier et al. (2016) do take into account the fact that risks can be correlated. However, this correlation pattern is fixed, while during crisis periods correlation patterns change dramatically. We show this feature in Table 1. We find that during the sovereign debt crisis of 2010-12, the government bond yields of the periphery countries under stress were highly positively correlated. At the same time these yields were negatively correlated with the yields of the core (safe) countries like (Germany, Finland, France, Netherlands).

The implication is that during crises it is very unlikely that the senior tranche in the SBBS can maintain its status of safe asset. It will consist of bonds investors dump and "safe-haven" bonds. The senior tranche will continue to depend on the cash flow generated by bonds that panicking investors deem to be extremely risky. The perception that this senior tranche is equally safe as the safe-haven sovereign bonds (e.g. German bonds) is very unlikely when markets are in panic mode. As a result, it is also likely that investors will flee the senior tranches of the SBBS to invest in the "real thing", i.e. super safe sovereign national bonds.

A third problem is related to the previous one. During normal times, the safe asset will have been used in the pricing of derivatives and other financial instruments and it will be an important part of the repo market providing liquidity in that market. As a result, a large part of the financial markets in the Eurozone will depend on the perceived safety and liquidity of the SBBS construction. When during crisis periods, the safety of that construction is put into doubt (as we argued in the previous section), liquidity will tend to disappear and the whole financial sector of the Eurozone will be at risk. In the end we may have more rather than less financial stability in the Eurozone.

There is an historical analogy here. During the boom years CDOs were created backed by different types of securities, e.g. mortgages. At the time, many people were enthusiastic about this and believed that CDOs would make the financial markets more efficient by a better spreading of risks. Ultimately, it was believed, this would lead to more financial stability. The SBBS proposed by the ESRB has the same CDO structure as the previous ones. It would be surprising that financial engineering, which in the past failed dismally in stabilizing financial markets, would do so in the future.

Conclusion

We have argued that various recent proposals aimed at stabilizing the Eurozone by financial engineering do not eliminate the inherent instability of the sovereign bond markets in a monetary union. During crises this instability becomes systemic and no amount of financial engineering can stabilize an otherwise unstable system.

The proposals made by the French and German economists (Bénassy-Quéré et al. 2018)) have clearly been inspired by concerns about moral hazard. These concerns are very intense among German economists and have left their mark on the reform proposals of the French-German group of economists. Moral hazard means that agents consciously take too much risk because they expect others to bail them out. It is very unlikely, however, that the sovereign debt crisis had much to do with moral hazard. It stretches the imagination to believe that the Greek, Irish, Portuguese or Spanish governments decided to allow their debt levels to increase in the expectation that they would be bailed out by the governments of Northern Eurozone countries. Our hypothesis that the sovereign debt crisis erupted as a result of a boom that led private and public agents to disregard risk makes more sense. But even if moral hazard was a cause of the crisis, those who took on too much risk will have learned that the punishment for being bailed out by Northern Eurozone governments is severe. It should by now be clear that no government would wish to be bailed out by these governments.

Stabilization by financial engineering will not work. Real stabilization of the Eurozone goes through two mechanisms. The first one is the willingness of the ECB to provide liquidity in the sovereign bond markets of the Eurozone during times of crisis. The ECB has set up its OMT-program to do this. However, OMT is loaded with austerity conditions, which will be counterproductive when used during recessions (which is when crises generally occur). That is why a second mechanism is necessary. This consists in creating Eurobonds that are based on joint liability of the participating national governments. Without such joint liability it will not be possible to create a common sovereign bond market. The creation of such a common bond market is the conditio sine qua non for long-term stability the Eurozone.

The political willingness to go in this direction, however, is non-existent today. There is no willingness to provide a common insurance mechanism that would put taxpayers in one country at risk of having to transfer money to other countries. Under those conditions the sovereign bond markets in the Eurozone will continue to be prone to instability.

The danger of financial engineering proposals is that they create a fiction allowing policymakers to believe that they can achieve the objective of stability by some technical wizardry without having to pay the price of a further transfer of sovereignty.

References

Benassy-Quéré, A., et al. (2018), Reconciling risk sharing with market discipline: A constructive approach to euro area reform, CEPR Policy Insight, no. 91,

Brunnermeier, M. Langfield, S., Pagano, M., Reis, R., Van Nieuwerburgh, S., Vayanos, D., (2016), ESBies: Safety in the tranches, ESRB Working Paper Series, no. 21.

De Grauwe, P., The Governance of a Fragile Eurozone, CEPS Working Documents, Economic Policy, May 2011

De Grauwe, P., and Moesen, W. (2009) 'Gains for All: A Proposal for a Common Eurobond', Intereconomics, May/June.

De Grauwe, P., and Ji, Y., (2013), Self-fulfilling Crises in the Eurozone: An Empirical Test, Journal of International Money and Finance, Volume 34, April, Pages 15-36

Delpla, J., and von Weizsäcker, J., (2010), the Blue Bond Proposal, Bruegel Policy Brief, May.

European Systemic Risk Board (ESRB), (2018), Sovereign bond-backed securities: a feasibility study; January.

Kindleberger, C. P. (1978). Manias, Panics and Crashes: A History of Financial Crises, Wiley.

Lane, Ph., and Langfeld, S., (2018), The feasibility of sovereing bond backed secutities in the euro area

Messori, and Micossi, S., (2018), Counterproductive Proposals on Euro Area Reforms by French and German Economists, Centre for European Policy Studies,

Minsky, H. (1986). Stabilizing an Unstable Economy. Yale University Press

Tabellini, G. (2017), "Reforming the eurozone: Structuring vs Restructuring Sovereign Debts", Voxeu.org, 23 November.

Table 1. Correlation of yields before crisis (2000M1-2009M12)

Table 2. Correlation of yields during crisis (2010M1-2012M09)

Table 3. Correlation of yields after crisis (2012M10-2017M12)

Source: European Central Bank and authors' own calculation

Note: The yields are yields on 10-year government bonds

[1] For a more general criticism of the French-German reform proposals, see Messori and Micossi (2018).

[2] In the ESRB(2018) proposal this tranche is split further into two tranches, a junior tranche proper with the highest risk (10%) and a mezzanine tranche (20%) which takes the losses after the junior tranche has been depleted.

- Paul De Grauwe is John Paulson Chair in European Political Economy, London School of Economics, and a former member of the Belgian parliament.

- Yuemei Ji is a Lecturer in Economics at UCL's School of Slavonic and East European Studies and a Fellow of the European Institute. She did her undergraduate studies in Economics at Fudan University Shanghai and obtained her PhD in economics from the University of Leuven in 2011. Prior to joining UCL, she was a post-doc researcher at the University of Leuven and then was a lecturer at Brunel University. She has been a visiting fellow at various institutions such as the European Institute at LSE and the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS) in Brussels.

Close

Close