Emmanuel Macron: The Audacity of Humility and the Hope of Moderation

15 May 2017

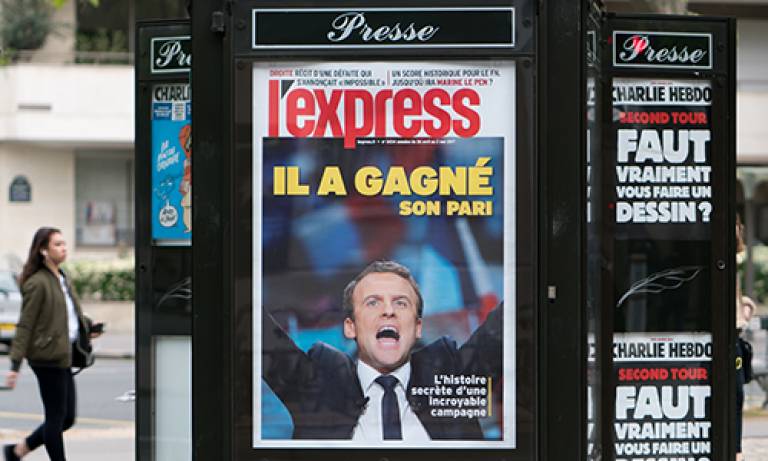

The election of Emmanuel Macron heralds the advent of humility and moderation as cardinal political values in French democracy, argues Aline-Florence Manent.

The most bizarre presidential campaign in French history has now finally come to a close. We should, of course, welcome the election of Emmanuel Macron as a beacon of hope for the future of liberal democracy in France, in Europe, and elsewhere in the world. But we shouldn't be too quick to conclude that Marine Le Pen's defeat signals a clear change of tide in the global populist ascendency. If anything, this election has demonstrated that even in the country of Voltaire and Montesquieu, in a nation that proudly asserts the legacy of the Enlightenment and the French Revolution, and considers itself to be the birthplace of universal human rights, democracy remains ever so precarious.

There are serious challenges ahead for President-elect Emmanuel Macron. The first one will be to eke out a coherent parliamentary majority after the June legislative elections. It is unlikely that his En Marche! movement will win a majority of seats in the National Assembly. He will thus have to be able to count on an alliance with centre-right and centre-left deputies invested by the traditional parties (Les Républicains, LR, on the right and the Parti Socialiste, PS, on the left) in order to form a majority and pass legislation. This will, however, depend on whether the LR and PS will want to work with the new President, and not resort to vindictiveness and punish him for their own inability to gain the trust of enough French voters (and make it into the second round of the presidential election).

But there are other challenges that Macron will have to tackle if he wants his presidency to mark a thorough renewal of French political culture and not just a cosmetic facelift. After the initial sighs of relief at Marine Le Pen's defeat, we should neither turn into complacency nor a moral indictment of Front National voters. We, as a society, should address the root-cause of what makes populism so appealing to so many today, across traditional socio-economic and demographic divides. We need to address the legitimate economic grievances of a large swath of the population that feels let down by the establishment, that has grown (rightly) intolerant of an economic system that creates wealth but fails to increase opportunities for work for many, and where the redistributive efforts of the welfare state are found wanting.

The fate of our liberal democracies, however, is not determined solely by economic factors. The Front National vote (like the Trump or Brexit vote) cannot be explained away by class-analysis alone. In fact, such explanations would not only be wrong but also insulting to the many voters who might be economically aggrieved and yet who remain staunch defenders of so-called progressive values.

If we are to durably dispel the menace of populism in France, as elsewhere, we need to revive voters' commitment to liberal democracy as a political and ethical project worth defending. Compensating for the vicissitudes of globalization and working towards a fairer redistribution of wealth will be crucial. But implementing such policies will be an uphill battle for President Macron, especially absent a clear parliamentary majority. Moreover, it will take time before the effects of such policies will become visible (this is one of the reasons why some analysts like Jacques Attali suggest France return to a non-renewable 7-year presidential term).

Other strategies might provide a more immediate impetus for translating inchoate hope into a genuine democratic renewal. We need to pre-emptively address the institutional cynicism that has made it possible for an unapologetically xenophobic and racist party to come so close to the gates of power.

It is worrisome that many self-proclaimed progressives such as Jean-Luc Mélenchon and his acolytes were prepared to play Russian roulette with the French Republic for the sake of the purity of their moral principles. The vilification of finance capitalism (and, by the same token, the many respectable men and women who make a living in this sector) as intrinsically malevolent and morally abject should be denounced for what it is: an aggressive dogmatism. No, being a banker is not "as bad as being a fascist." There aren't just multiple degrees of separation between the two. They are simply not on the same metric system: one is an occupation, the other is a creed. Working in an industry that has morally objectionable business ethics (which should be addressed) is not on par with supporting xenophobic, racist and illiberal political ideologies out of personal conviction.

Secondly, it might be time to rekindle our historical memory. It is remarkable that older generations were the ones who voted in significant proportions for Emmanuel Macron. This may not be as surprising as it first appears. Sure enough their vote might testify to the conservatism of an older electorate (despite its cultural conservatism, Marine Le Pen's proposals, such as a 'Frexit' were far more radical than what Macron proposed). But this is also a generation who has experienced Europeanization as a peace-project, a generation whose fathers and grand-fathers fought and died for the ideals that too many today seem prepared to casually gamble away. As Samuel Moyn writes, "history is worth consulting when it rhymes."

France should also recall the ways in which democracies most frequently die. As the example of Weimar Germany has shown, they are most often endangered from inside, when forces inimical to the values implicit in liberal democracy-tolerance, pluralism, inclusivity, and solidarity-use the institutional channels of the democratic system to come to power and hollow them out in the name of "true democracy." The ascendency of illiberal forces within democracies is often helped by the inability of committed democrats to put aside their political quibbles to defend the Republic. Mélenchon's refusal to symbolically join forces with Emmanuel Macron against the far-right is chilling when one recalls that an alliance between German Socialists and Communists could have prevented Hitler's accession to power in 1933.

There are other lessons to be learned from Germany in France today. Germany's path towards a stable and vibrant liberal democracy was a belaboured one. It had many components, one of which was a long and arduous process of working through its past. An honest reckoning with France's own not so glorious past is long-overdue. There are many disquieting lessons to be learned from the darker sides in France's history: from the violence of the French Revolution to the rampant anti-Semitism crystallized in the Dreyfus Affair or the atrocities committed by French colonialism in the name of its "civilizing mission." When Emmanuel Macron suggested that France committed "crimes and acts of barbarism" in its colonization of Algeria that would be considered as "crime against humanity" today, his remarks were met with a degree of acrimony and public outrage usually reserved for acts of high treason. At the time, Macron apologized, although he did so without completely disavowing his remarks. Now the campaign is over and PR considerations can, hopefully, recede to the background, it would be a salutary and powerful symbolic gesture for Macron to fully own-up to his Algiers speech. This will be met with outrage by some. They will shout loudly and stomp their feet. Let them. In due course, wrestling with France's fraught history might encourage a more charitable outlook towards immigrants, refugees, and minorities, and render even latent xenophobic and racist prejudices unacceptable. It will also be a powerful symbolic gesture towards reconciling a disillusioned youth with the Republic.

If exclusionary discourses that form the bread and butter of populism flourish in an age of complexity and ambiguity, the greatest task at hand for intellectuals and commentators will be to invent a crisp, intelligible, and emotionally resonant narrative in defence of the openness of liberal democracy. A narrative that dispels the temptation to resort to facile and unilluminating Manichaeism. A narrative that does not condemn us to choose which of the three founding principles of the French Republic should take precedence over the other. A narrative that finally makes it clear that our democracy can and should, "at the same time" (Macron's signature phrase), strive to remain faithful to the ideals of liberty, equality, and solidarity.

It is a precarious equilibrium to strike, one that necessarily always remains open to revision and readjustment. It cannot easily be enshrined in a miraculous blueprint or a catalogue of magic reforms. More than a set of policies, it is first and foremost an ethos, an attitude of humility. If democracy remains a daily plebiscite, as Ernest Renan famously asserted, one ought to accept that it is a trial-and-error process, and not a matter of finding the perfect redeemer.

By becoming the youngest president in the history of French democracy, Macron has already made the pages of history books. He is poised to fundamentally reshape French democracy. For this, he must first and foremost stay true to the humble attitude that became his most distinguishing feature in this campaign. His enlightened pragmatism is truly audacious. He should embrace the audacity of humility and the hope that moderation bears for French politics in a more fulsome manner. Until he does so, it will be all too easy for his opponents to deride him as timid, hesitant, confused, or vapid. The values that animate Macron's political project are intrinsic to postwar liberal democracy: humility and responsibility, an appreciation for complexity, rejecting both certainties and uncertainties, embracing pluralism, tolerance, openness, and Europeanization.

Macron will certainly fall short of all the hope that is placed in him. The question is, will French voters emulate his characteristic humility in 2022. One can only hope that they will keep in mind the words of Albert Camus:

"Who after all this can expect from him pre-packaged solutions and high morals? Truth is mysterious, elusive, always to be conquered. Liberty is dangerous, as hard to live with as it is elating. We must march toward these two goals, painfully but resolutely, certain in advance of our failings on so long a road."

Image of Emmanuel Macron (C) Lorie Shaull (CC BY 2.0).

- Aline-Florence Manent is a historian of political thought and a research fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, University College London. She writes about the history and theory of democracy in twentieth century Europe and tweets about contemporary politics at alineflorencemt.

Close

Close