In and Out of Focus: An Academic in the Sights of the Securitate 1965 to 1989

2 December 2015

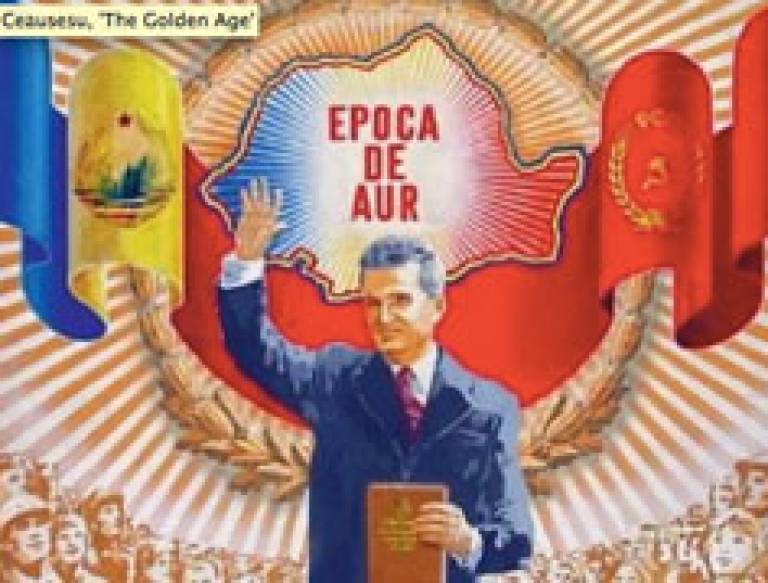

26 years after the the Romanian Revolution of December 1989, Dennis Deletant, Emeritus Professor of Romanian Studies, reminisces on his work under the Ceaușescu regime.

An inescapable feature of life in Romania under Nicolae Ceaușescu was the ubiquity of the Securitate or the security police, known officially for much of the period as the Department of State Security (Departamentul Securității Statului) of the Ministry of Internal Affairs. I realized as much from my first contact with the country in 1965 and was not surprised to discover after the downfall of Ceaușescu that my professional and personal involvement with Romania, which encompassed the entire duration of his rule, from 1965 until 1989, should attract the Securitate 's attention. My professional association with the country was cemented by my appointment as Assistant Lecturer in Romanian language and literature at SSEES on 1 October 1969, after having completed a nine-month British Council bursary in Bucharest during which time I gathered material for my PhD, a textual and linguistic study of a 17th century Romanian manuscript.

In January 2006, a revision in Romania of the Law on Access to the Archive of the Securitate enabled non-Romanian citizens to apply to consult their personal files. I did so in the following month. Six volumes were produced, three containing paper copies of materials compiled by various sections of the directorate of internal security, and a further three microfilmed by the current intelligence service from original reports drawn up by the foreign intelligence units of the Securitate and photocopied by the CNSAS, the National Council for the Study of the Securitate Archive. They total some 1500 pages and cover the years 1965 to 1989. I was given the accolade of being “an agent of British intelligence” since I was on the staff of SSEES, characterized in my file as “an agency of British espionage”.

As with other machines of political oppression the Securitate's most potent weapon was fear, and the depth of its inculcation into the Romanian population provided the principal reason for its success. Fear induces compliance and is therefore a tremendous labour-saving device. The Securitate’s numbers were far smaller than popular myth would have us believe. Records indicate that in 1950, that is two years after its creation, the number of personnel of all ranks totalled almost 5,000. In December 1989 this number had risen to 15,312. By adding the security troops command (Comandamentul Trupelor de Securitate), which numbered 23,370 officers, men and women, the total staff of the DSS at the time of the 1989 revolution was 38,682. The population of Romania stood at 23 million. By comparison, in East Germany the personnel of the Stasi numbered 91,000 in 1989.

That first contact with Romania was my attendance in 1965 at a summer school in the mountain resort of Sinaia, some 100 miles to the north of the capital, Bucharest. One Sunday I was allowed to venture out from the complex in which we foreign students were quartered. In the town I was immediately intrigued by the fact that people of all ages stared at my clothes and, in particular, at my shoes. The latter, I learned, were the conclusive hallmark of a Westerner, since Romanian items of clothing were uniform Standard de Stat or “state-standard product.” Only on one occasion did a trio of young Romanian students summon up the courage to ask me where I was from. On hearing I was British they invited me for a “coffee.” I was led to a log cabin in the surrounding forest from where, as we approached, I caught the strains of “Norwegian Wood” by The Beatles. Inside, it was crammed with teenagers in animated conversation against the background of music from a jukebox. Successive songs were from an album by the same band, and my friends eagerly asked me to augment their fragmentary understanding of the lyrics. This I did, adding translations where necessary in my faltering Romanian. Eventually, feeling that they were in my debt, I enquired why no ordinary Romanians came up to the summer school complex. They laughed, looked around and invited me to walk with them. ‘’You see,” they said, “we live in a socialist country, and here the state maps out your life for you from birth. You are assigned a school, you are assigned a job and you are assigned a place to live. Conformity is the rule; you do what you are told and meeting foreigners is off-limits. If your expectations are low and you don’t step out of line, then you will be satisfied. And to make sure that you don’t step out of line, they have the Securitate.”

During the late 1980s I often spoke out on BBC Radio against Ceausescu’s gross abuses of human rights. Yet, to my surprise, I was given a visa in September 1988 to re-enter the country. My observations of that visit were encapsulated in an article in The Times, under the byline “From a Special Correspondent,” which appeared on Oct. 8, 1988. Two months later, I was informed that I had been declared persona non grata. I prepared myself for a long interval of exile from my second home, only to be caught completely off guard by the sequence of events in Timișoara and Bucharest that led to Ceausescu’s overthrow on 22 December. I was even able to claim a presence in Romania in 1989 for, thanks to BBC Television and especially to its chief foreign affairs correspondent John Simpson, I returned to Bucharest on 29 December and indulged myself in the idea of a Romania without the Securitate. Today, it is corruption that corrodes democracy in Romania, and the younger generations, with the help of the EU and the US, are leading the fight against it.

Dennis Deletant is Emeritus Professor of Romanian Studies at SSEES, UCL and Ion Rațiu Professor of Romanian Studies in the Center for Eurasian, Russian and East European Studies, Georgetown University, Washington DC. On 27 November 2015 he gave a lecture on his experiences in UCL’s Gustav Tuck Theatre as part of the series of lectures, seminars, and events celebrating the Centenary of the UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies.

Note: The views expressed in this post are those of the author, and not of the UCL European Institute, nor of UCL.

Close

Close