Promoting LGBT rights at home and abroad: the role of the EU

6 December 2013

While Europe has emerged as a world-leader in terms of the protection of LGBT rights, standards differ markedly from one EU Member State to another. As the EU still has much to do to promote LGBT rights internally, how can it effectively criticise states beyond its borders?

Dr Richard Mole

In June 2011, United Nations Secretary-General Ban Ki-moon announced that ‘acts of violence committed against individuals because of their sexual orientation and gender identity’ was ‘an attack on the universal values that the United Nations and I have sworn to defend and uphold’. With these words respect for LGBT rights was promoted by the United Nations as a universal value. However, this is a view that is far from being universally accepted.

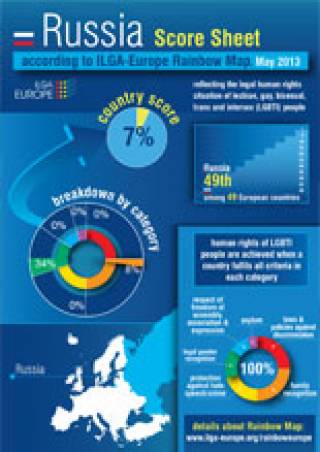

In terms of the respect for and protection of LGBT rights, Europe has emerged as a world-leader. Since the inclusion of sexual orientation in the EU equalities agenda through Article 13 of the Amsterdam Treaty, there has been increased pressure at the European level for existing members and accession states to promote the equal rights of their LGBT citizens. Despite similar top-down pressure, however, the legal situation for LGBT people in the EU differs markedly from member-state to member-state in terms of the type and the extent of the rights accorded or indeed whether rights have been accorded at all, as is clear from ILGA-Europe’s Rainbow Map.

As we can see from this year’s Rainbow Map, the situation in Europe is very mixed and complex. Even among EU member-states, we can see considerable variation between the UK on 77% and Bulgaria and Italy on 18% and 19%, respectively. The map also demonstrates that the myth of the Eastern half of Europe being less progressive than the West in terms of respect for LGBT rights is untrue in many cases. Hungary and Croatia outperform Austria, Switzerland, Finland and Ireland, while the legal situation for LGBT individuals in the Czech Republic, Slovenia and Albania is judged to be better than in Italy and Greece. The EU therefore has much work to do to promote LGBT rights among its own members, which, one might argue, undermines its legitimacy in criticising states beyond its borders.

The ban on ‘homosexual propaganda’ must be understood as part of Putin’s on-going at-tempt to entrench Russian traditional values in the face of the spread of Western liberal ideas, which he blames for corrupting the nation’s youth and fomenting opposition to his rule. The ban offers further evidence of the socially conservative ideology Putin has espoused since returning to the Russian presidency in 2012 as well as the close relationship between the Kremlin and the Orthodox Church, the political support of which was instrumental in Putin’s re-election.

While the threat of prosecution and violence should not be underestimated, a more dam-aging consequence of the law for the situation of LGBT individuals in Russia is the association of homosexuality with criminality. The ability of activists to convince the general population that LGBT individuals deserve equal rights is seriously undermined if the latter are constructed as criminals. The law thus seeks to silence anyone attempting to counter political discourse in which homosexuals are depicted as social deviants, paedophiles or mentally ill, and to grant homophobes an exclusive voice and legitimate moral leadership in public debates about sexuality.

While the law has provoked international outrage and calls for a boycott of the Sochi Olympics, international pressure is so far having little impact on Russia. In June, for the first time in its history, a Council of Europe conference of ministers ended without a declaration being adopted, due to Russia's opposition to an item referring to the requirement to combat discrimination and the violation of rights of LGBT youth. Moreover, the Russian authorities still refuse to allow a Pride parade to go ahead in Moscow, despite the judgement against them by the European Court of Human Rights. Given Russian intransigence, it is unclear what the EU can do to convince Moscow of the need to protect its LGBT citizens.

- Dr Richard Mole, UCL School of Slavonic and East European Studies

- Related event: The 2013 Sakharov Debate, Promoting LGBT rights at home and abroad: the role of the EU, 6 December 2013, Europe House.

- Download the ILGA-Europe Rainbow Map 2013 (4MB, PDF) and the ILGA-Europe Russia Score Sheet 2013 (2MB, PDF).

Close

Close