Meet the Staff: Dr Phil Mannion

6 December 2021

Dr Philip Mannion, Lecturer in Palaeobiology: the fossil record has a critical role to play in our understanding and forecasting of the ongoing biodiversity and climatic crisis, as we sleepwalk into a sixth mass extinction.

I was a PhD student and postdoc in the department from 2006 to 2011, returning as a lecturer in 2019 after research fellowships in Berlin and at Imperial College London. Returning felt a little like coming home, although the department has undergone major renovations in that time, and I’m pretty certain that the position of my old desk is now one of the first-floor bathrooms…

I’m a palaeobiologist who retained my interest of prehistoric life into adulthood, stumbling into a PhD on the largest animals to ever walk on land, the sauropod dinosaurs. In a Sliding Doors moment, I came dangerously close to doing a PhD on fossil echinoids instead... My research on the giant sauropods includes their anatomy and evolutionary interrelationships and has taken me to every continent (other than Antarctica) to study their remains. This has led to me collaborating with researchers from across the world, including naming new sauropod species from Argentina, Australia, China, France, Portugal, Switzerland, Tanzania, and the UK. It has also led to me eating some fairly unusual things, with sea cucumbers and cow udders now firmly on my veto list when it comes to restaurant suggestions.

Caption: Vouivria damparisensis, a sauropod species I named from the Late Jurassic of France (artwork produced by Chase Stone).

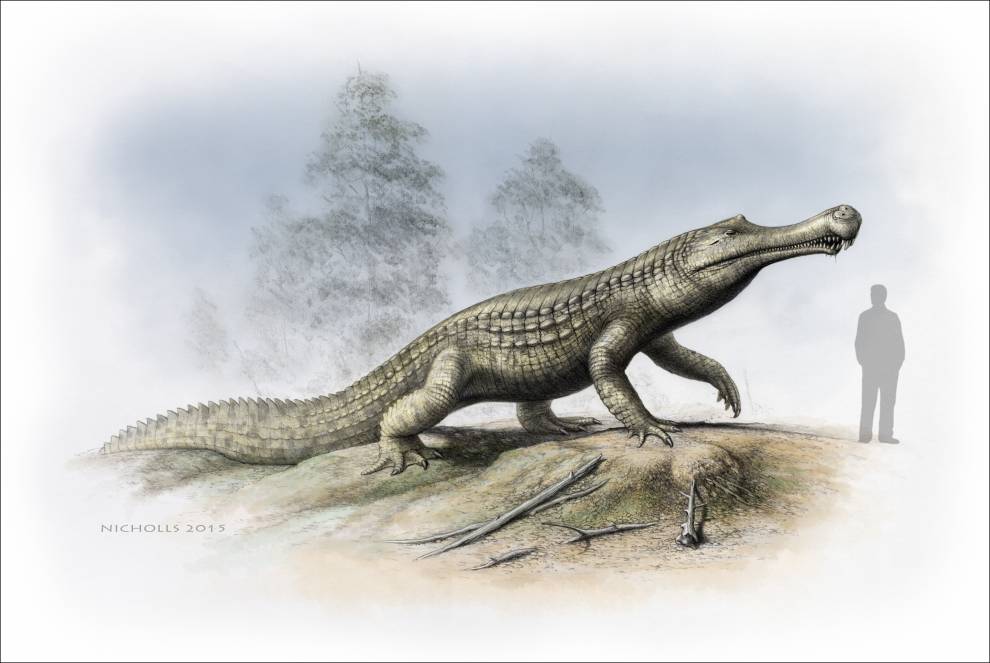

My research interests have expanded to include other groups, with increased focus on crocodiles and their extinct relatives. As with sauropods, this includes their anatomy and reconstructions of evolutionary relationships, but also attempts to understand how the crocodile group has dwindled to just 25 species today. The rich, past diversity of crocodiles reveals giant forms >9 m length, species capable of running, fully marine animals with flippers, and even herbivorous species. They also lived up in the Arctic, so almost nowhere on Earth was safe, although the small, herbivorous ones might have at least made good pets. This research on crocodiles has partly been driven by several excellent students, including a current PhD student in the department, Cecily Nicholl, and will be developed further with a newly started postdoc, James Hansford.

Caption: Sarcosuchus imperator, a 9-metre-long crocodile relative from the Early Cretaceous of north Africa (artwork © Bob Nicholls/Paleocreations.com)

“In parallel with my work on sauropods and crocodiles, my research seeks to understand how vertebrate biodiversity has fluctuated through time and space. This includes the role of mass extinctions, such as the K/Pg event that wiped out the non-avian dinosaurs. Much of this research focuses on time intervals characterized by stark climatic fluctuations, including warmer intervals that are potentially analogous to near-future scenarios, as well as transitions between warm-house and cold-house climate states.

Increasingly, my research aims to understand how these past climatic changes constrained the evolution and distribution of ancient biodiversity. This includes work led by another fantastic PhD student in the department, Miranta Kouvari. As part of this, we incorporate high-resolution climate model data and ecological modelling into analyses including fossil and present-day species data. This provides key information on past distributions of biodiversity that can also shed light on its future.

Although many people think palaeontology is entirely about naming new dinosaurs (and clearly, it is part of it!), it is also our only window into how organisms have responded to climate change, providing the only empirical evidence of ‘normal’ extinction rates and ‘pristine’ environments prior to human-driven disturbances. As such, the fossil record has a critical role to play in our understanding and forecasting of the ongoing biodiversity and climatic crisis, as we sleepwalk into a sixth mass extinction. With such cheerful thoughts to conclude on, Happy Holidays!

Links:

- Dr Phil Mannion's academic profile

- Asteroid impact, not volcanoes, made the Earth uninhabitable for dinosaurs.

Close

Close