|

|

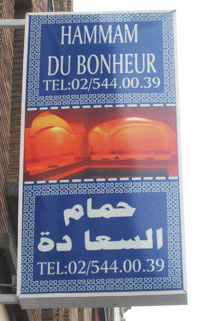

Language and educationIn view of the multilingual situation in Brussels, you would expect bilingual or multilingual education to be the order of the day. However, that is not the case because the >language laws of 1963 do not allow education in another language, unless foreign language education is concerned. There are exceptions such as international schools and the experiments of integration centre De Foyer. There are a number of schools that offer home language and culture classes, but their main aim is to ease the transition to monolingual Dutch or French education. Education in Brussels is either Dutch or French and is organised by the Flemish and French Communities respectively. language education policy There are two independent education systems in Brussels; the Flemish and the French Community one. Brussels inhabitants are free to choose between the two, so education is essentially monolingual. Nevertheless, most students graduate at the age of 18 (compulsory school age) with knowledge of two or three foreign languages. They tend to start with the other national language (Dutch or French) in the third year of primary school. A second foreign language, usually English, is initiated at the beginning of secondary school. Students can choose to learn a third foreign language in the last years of secondary school and here, the choice really depends on the school. Traditionally, German is the preferred choice, but Spanish, Italian or other languages are also possible. (see table >language skills). In this respect, Belgium is ahead of the >EU guidelines and Belgians like to see themselves as front runners in terms of foreign language education, even though this popular assumption has been refuted by research. There is a growing body of opinion that language education would be more effective if multilingual education were possible and would be offered from nursery school onwards. In multilingual education, the foreign language is used as an instruction language, which means that students receive tuition in that language for several subjects, e.g. history or geography. When asked, 80% of the population said to be in favour of multilingual education. Unfortunately, this is not possible by law, because of the >language laws of 1963, which do not allow tuition of general subjects in foreign languages. Especially on the Flemish side do people resist a change in the law. There is still a lingering fear of Frenchification, even though that is highly unlikely, given the current, relatively strong, position of the Dutch language. (>see turning point for the Dutch language). Flemish schoolsIn the past, Dutch speaking residents in Brussels would send their children to French medium schools, because knowing French was a prerequisite to building up a professional career. A lot has changed in the past thirty years. In the seventies, the Flemish government initially invested in child care and nursery education and as such, created a solid base for more Dutch medium primary and secondary schools. But the number of children that spoke exclusively Dutch at home reduced steadily. That is why policy makers decided to extend their target audience to the ‘minorities’. In the mean time, Dutch had gained strength economically and socially and the new policy was very successful. So even though only 10% of the Brussels population is Dutch speaking, 18% of all its school children attend Flemish schools. And it is not only children from minority backgrounds, but also an unexpected number of bilingual children and French speakers who, in the past, would invariably have gone to French schools. In fact, the success was so large that the number of monolingual Dutch children in Dutch medium nursery schools is now under 15%. This number does increase in primary and more so in secondary schools. In 2001, about half of the students in Flemish secondary schools were monolingual Dutch speakers, 11% only spoke French at home and another 9% used other languages (more than 50 in total). These results were not foreseen and did present a problem for the Flemish schools. After all, the core aim of establishing these schools was to strengthen the Flemish presence in Brussels, but this is hard to do when less than half of all pupils speak Dutch at home. The majority of Flemish schools react rather negatively and mainly attempt to preserve the Flemish character of the school. As a result, they focus on language acquisition and language tests upon enrolment and there is no or hardly any interest in the home languages of these pupils. A minority of schools subscribe to a different view and try to accommodate speakers of other languages with home language and culture classes. home language and culture classesOnderwijs in Eigen Taal en Cultuur (OETC) The Council of Europe agreed a guideline in 1976, which was aimed at accommodating children of immigrant workers better in the educational systems of their ‘guest countries’. Analogous to the trends in >immigration policy, the purpose of this guideline, was to facilitate the potential return of children to their home countries. That is why children of foreign descent were offered classes in their mother tongue. When it became clear in the mid eighties, that a return was not an option for the large majority of migrants, the policy was adjusted with a focus on the integration of >allochtonous pupils. From 1982 onwards, schools have the right to organise OETC/ELCO. In reality, most participating schools opt for a minimal form whereby a few language groups receive two to four hours of classes in home language and culture. Nonetheless, the legal basis for OETC/ELCO remains problematic due to the >language laws which means it cannot be further developed structurally as it cannot be part of the curriculum and there is no official registration or evaluation, nor can attainment targets be set. Because of the extra-legal status of OETC/ELCO, schools depend on tutors from abroad, who are paid by the country of origin as the Flemish or French Communities don’t have the right to hire or pay these teachers. As a consequence, the success of OETC/ELCO really depends on the enthusiasm and effort of a number of schools. This is not tenable in the long term, which is why this type of education has dwindled in the last decade and is currently nearly extinct. >Read an interview with a director of a Flemish school in Brussels. differences between Flemish and French policyThe general vision on >integration of the Flemish and French speaking Communities can also be traced in their respective treatment of allochtonous children in education. Flemish community OETC in Flemish schools in Brussels is organised by the Regional Integration Centre De Foyer (@www.foyer.be) [Multilingual website of the integration and service centre De Foyer], which has successfully been organising all sorts of projects around multiculturalism for 35 years. They started an experiment in bicultural primary schools in the eighties. This meant that 50% of all classes would be taught in another language (Arabic, Armenian, Italian, Spanish and Turkish). The share of the foreign language is reduced towards the end of primary school. 7 out of 12 of the original schools that participated in the project, are still running it, in Spanish, Italian and Turkish. Legally, De Foyer has received an exception in order to do this. There are very few secondary schools that continue with any form of OETC. Only national languages of >allochtonous minorities are eligible for OETC. This way, the Flemish policy makers want to prevent French from ‘creeping into’ their schools. This fear for Frenchification is in sharp contrast with the authorities’ enthusiasm for ‘diversity’. A genuine attempt is made to present a multi-ethnic and tolerant image, an image that fits the Flemish global economic policy; an open, diverse and prosperous region.  In any case, this enthusiasm on the part of the authorities is not always shared by people in the educational field or the population at large. A rather persistent attitude prevails, which could possibly be explained by the historical Flemish struggle for emancipation from the French speakers. On the other hand, there is some sympathy for the emancipation of minorities, paradoxically enough as a consequence of that same history. For that reason, the integration model proposed by the Flemish government is a ‘fitting in model’, which means: social-economical integration with preservation of culture of origin. More recently, schools that offer OETC classes or extra Dutch lessons will also have to organise ‘intercultural education’ for their >autochthonous pupils. They can decide for themselves whether this will be a separate subject or part of other subjects, which is not unusual for that matter, as educational practise in Belgium is fairly free. The government sets guidelines and attainment targets, but the schools decide how to implement those individually.French CommunityThe implementation of ELCO in the French Community is rather slow and when it is finally introduced, it is mainly because of fear of a reprimand from the European end. The reason is that the whole idea does not fit their philosophy. Initially, the focus of their policy was to reduce the socio-economic disadvantage of migrant children. ELCO fits that picture nicely and the French Community enters into an agreement with Spain, Italy, Portugal and later also, Morocco. Just as in Flanders, there is very little structural support for the foreign teachers. Enthusiasm diminishes and at the end of the eighties, the focus shifts from home language education to intercultural education, so that autochthonous pupils too will receive classes about the culture of >allochtonous pupils. The purpose is to facilitate integration by means of mutual understanding. In the end, what is hoped for is that by means of this co-operation, badly performing migrant children will more easily acquire the French language and culture and improve their school results. To pay attention to their ethnic and cultural background would be frowned upon in the philosophy of French policy, because it is considered private. Their aim is always to create a cohesive and relatively homogeneous society and as a consequence, diversity is considered a threat. According to this idea, assimilation of the majority French language and culture is paramount. cracks in the monolingual front? Home language and culture education is on shaky legs because of the >language laws of 1963. At the same time, the increasing demand for multicultural and bicultural education is halted by this legislation too. This situation is not tenable in the long term, even more so because of evolutions on European level and certainly in a city like Brussels. In both Flemish and French speaking education, there is now a form of bicultural education and it would only be logical that ‘other languages’ would receive a place in the curriculum too. The original idea behind OETC/ELCO was to maintain home languages for when migrant children would have to go ‘back’ home. Reality has proven to be different and the various groups in society evolve and diversify all the time. So it would make a lot more sense to teach all pupils about this diversity and how to deal with it. Particularly in the multilingual and multicultural environment that Brussels presents, it should really be possible to offer education in a variety of languages and not only the national ones, but also other frequently used languages. quote from Piet van de Craen, professor at VUBThe advantages of multilingual education are countless. First of all, multilingual education leads to a better knowledge of the second national language and later on, to a better knowledge of other foreign languages. For bilingualism has now become outdated: European citizens should become multilingual. Secondly, multilingual education leads to a better understanding of the subject matter on offer, as it stimulates curiosity and learning ability. Thirdly, multilingual education leads to a more open personality and more tolerance. Fourthly, multilingual education leads to a better development of the brain. Young brains that are stimulated early, will develop faster and more efficiently than others. Finally, multilingual education meets a large social demand that is currently present. source: www.manifestobru.be As far as bilingual education is concerned, a few steps in that direction have been made. Since 1995, it is possible in the French Community to offer part of the classes in Dutch. Even though the language laws are violated here, no questions are asked. There are three such schools in Brussels and 39 in Wallonia. Since 2001, there are a few Flemish schools in Brussels that have decided to offer other subjects in French, during the normal hours of French as a foreign language. This way, they have nicely sidestepped the language regulations, because they are doing it during the dedicated time for French. Moreover, since 2004, the Flemish government has decided to meet the demand to offer foreign languages from an earlier age. Primary schools are now allowed to give ‘language initiation’ in another language. That language would have to be French in the first place, but other languages can be offered later on. You could say that the latter is definitely a step in the direction of the recognition of multilingual education, but –anno 2006- the language laws remain unchanged. Without a doubt to be continued. |