Loading...

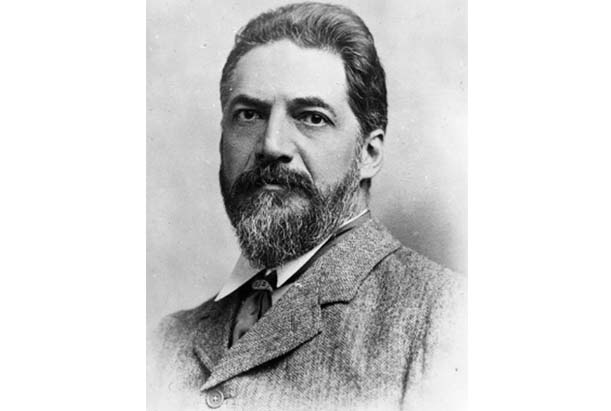

Petrie's Life

Scroll through the decades in the life story of the remarkable William Matthew Flinders Petrie, featuring archive images and quotes by him and those who knew him.

Drag anywhere to explore

Click/tap on an image for more details

-

1853 — 1862

1853

-

1853-1862 Summary

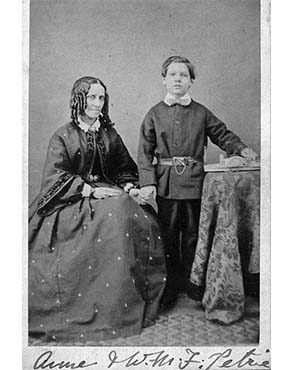

William Matthew Flinders Petrie was born 3 June 1853, the only child of Anne Flinders and William Petrie. Anne was the daughter of Captain Matthew Flinders, who was famous as an explorer of the coasts of Australia.

-

Petrie's early childhood

In his early years, Petrie was home schooled, but his health was not strong. Nonetheless, some of his lifelong interests, such as a fascination with weights and measures were already beginning to emerge.

Petrie's interest in history and archaeology became apparent at an early age. After a visit to Carisbrooke, Isle of Wight, Petrie was horrified at the archaeological techniques used.

“When I was eight, a little boy of ten used to come visit us….and he described the unearthing of a Roman villa in the Isle of Wight; I was horrified at hearing of the rough shovelling out of the contents, and protested that the earth ought to be pared away inch by inch, to see all that was in it and how it lay. … I was already in archaeology by nature.”

-

-

1863 — 1872

1863

-

1863-1872 Summary

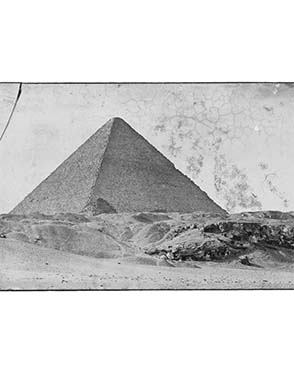

Petrie was first drawn to the pyramids by the theories of the time that speculated, amongst several ideas, that the ancient Egyptians built the pyramids with the understanding of Pi (3.14).

1873

-

Petrie's adolescence

Petrie was first drawn to the pyramids by the theories of the time which speculated, amongst several ideas, that the ancient Egyptians knew the value of PI and had built the pyramids to demonstrate their knowledge of it.

A new stir arose when one day I brought back from Smiths’s bookstall, in 1866, a volume by Piazzi Smyth, Our Inheritance in the Great Pyramid. The views, in conjunction with his old friendship for the author, strongly attracted my father, and for some years I was urged on in what seemed so enticing a field of coincidence. …it was this interest which led my father to encourage me to go out and do the survey of the Great Pyramid….

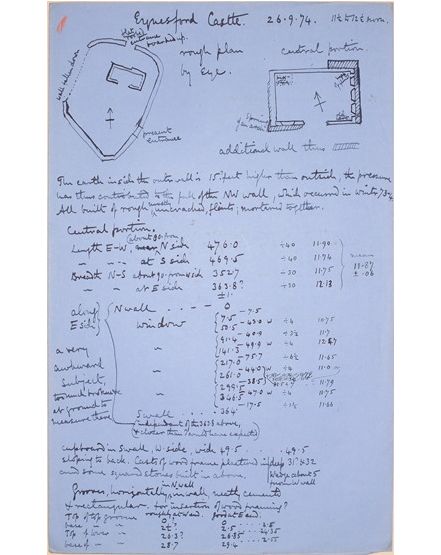

Another activity of his youth was surveying ancient monuments in southern England with his father.

I had a preliminary canter at accurate surveying with my father at Stonehenge in 1872….

-

-

1873 — 1882

1873

-

1873-1882 Summary

-

Petrie in his 20's

After years of planning, Petrie finally arrived in Egypt to survey the pyramids in December 1880. He was also interested in how they might have been built and looked for evidence of stone working technology. However, working in such a public tourist area presented challenges.

It was often most convenient to strip entirely for work, owing to the heat and absence of any current of air, in the interior. For outside work in the hot weather, vest and pants were suitable, and if pink they kept the tourist at bay, as the creature seemed to him too queer for inspection.

Petrie’s work disproved the radical ideas about how and why the pyramids had been built. However, he remained critical of those who maintained the old ideas in the face of the scientific evidence.

The fantastic theories, however, are still poured out, and the theorists still assert that the facts correspond to their requirements.

-

-

1883 — 1892

1883

-

1883-1892 Summary

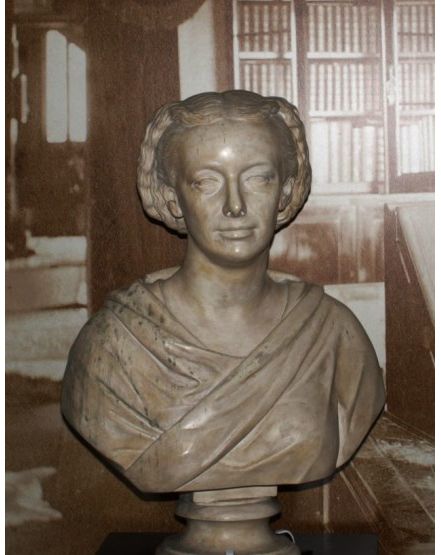

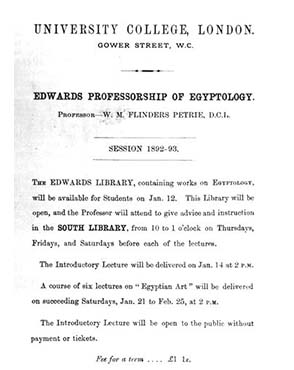

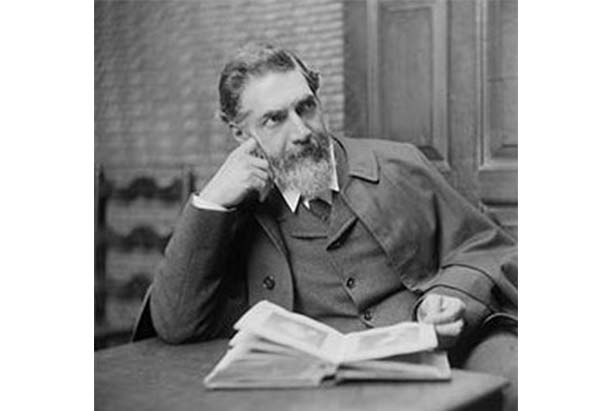

This was an important decade for Petrie. It began with his first formal excavations in Egypt, undertaken in the Delta and carried out through the newly-formed Egypt Exploration Fund, which also led to his close friendship with the Fund's founder, Amelia Edwards. His future changed dramatically at the end of the decade when the endowment left by Edwards, who died in 1892, led to Petrie's appointment as the first Professor of Egyptology at University College London.

-

Petrie in his 30s

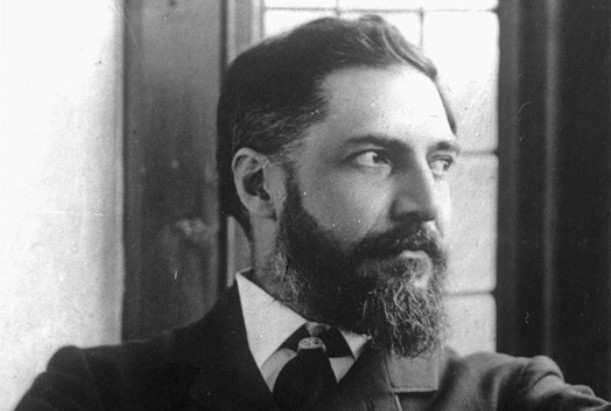

While in Egypt, Petrie learned that a new society had been formed to excavate in Egypt, the Egypt Exploration Fund. This was the brainchild of the novelist, Amelia Edwards, who was appalled by the destruction of monuments she saw whilst visiting there. Petrie was one of the first excavators for the fund and he and Edwards became fast friends.

The death of a major benefactor to the EEF led the Committee to choose between Petrie and their other excavator, Edouard Naville. The Committee chose Naville; Amelia Edwards was furious, and Petrie resigned, but found funding for a trip to Egypt in 1886 to record images of foreigners on the monuments. His supporters in this included General Pitt-Rivers and Francis Galton, who was interested in this as part of his research into race.

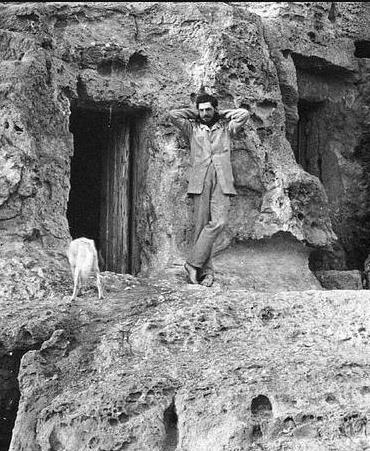

In 1891-2, Petrie explored Amarna, the ancient capital city of Akhenaten, and his queen, Nefertiti. With its well- preserved state buildings and settlement areas, the city was initially quite daunting to Petrie but his predictions for the potential of the site were certainly correct.

It is an overwhelming site to deal with. Imagine setting about the ruins of Brighton, for that is about the size of the town: and then you can realise how one man must feel with such a huge lump of work….This place would need a lifetime of work to exhaust it properly…The palace of Khuenaten [Akhenaten] I have fixed for certain I think….to thoroughly exhaust this site will probably coat £200 or £300; but it is the most promising place for (1) pieces of the finest carving and glazed work of that age (2) valuable things hidden or lost (3) any historical objects such as papyri or clay tablets…

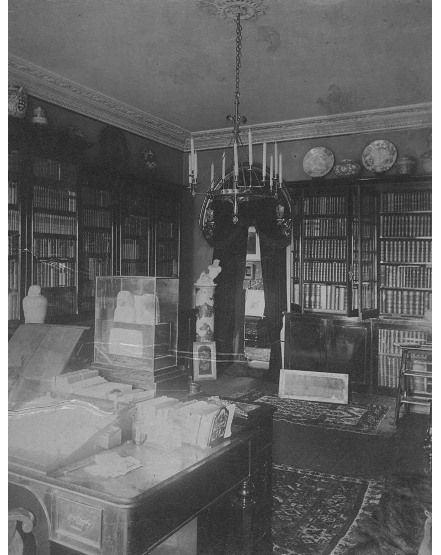

1892 was a momentous year for Petrie. While excavating at Amarna, he learned that Amelia Edwards had died. In her will, she had left an endowment for a Professorship of Egyptian Archaeology and Philology at UCL, intending Petrie as the recipient. She also bequeathed her library, photographs and collection of Egyptian antiquities to the college.

-

-

1893 — 1902

1893

-

1893-1902 Summary

As the new Professor of Egyptology, Petrie divided his time between UCL and Egypt. In the course of his many excavations during the period, Petrie made some of his most significant contributions to archaeology, with developments in recording, object typologies and dating. Petrie married Hilda Urlin, who became his co-worker in both England and Egypt.

-

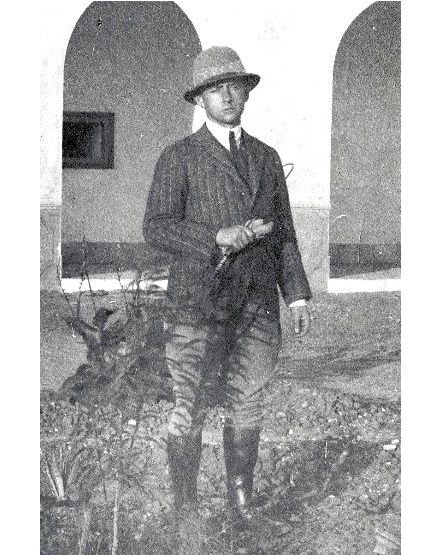

Petrie in his 40's

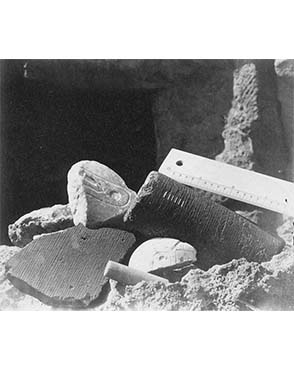

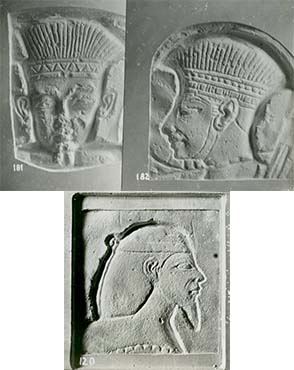

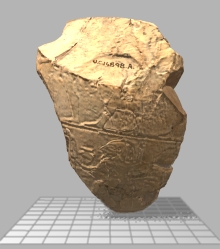

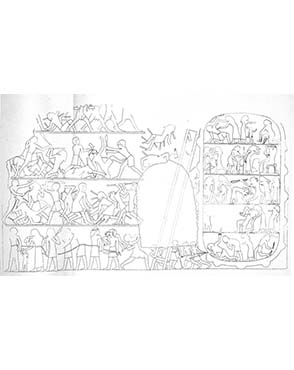

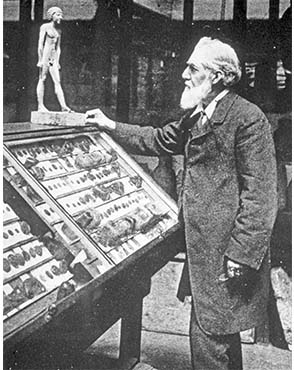

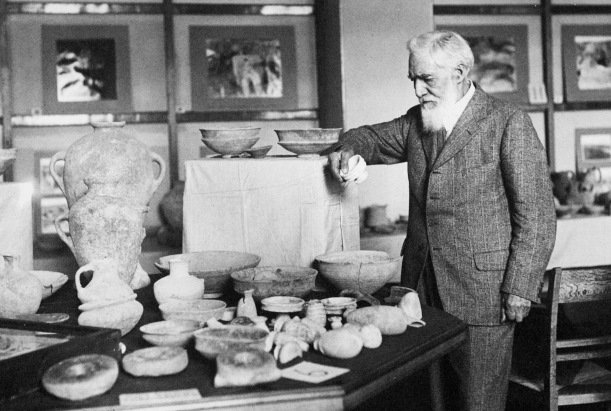

Petrie began unpacking Amelia Edwards’ ancient Egyptian collection, as well as his own, in the new Egyptology Department at UCL, its home until 1940. Students began to accompany Petrie to Egypt. One of these students was James Quibell, who worked at Hierakonpolis, where the mace head shown here was found.

Petrie was notorious for the lengths he would go to in order to avoid meeting visitors. A young student, Arthur Weigall later recounted how he visited the museum and, while viewing the displays, first encountered Petrie. Weigall was to become Petrie’s assistant in the museum in 1902.

I made a quick movement round the case, and there behind it I found the Professor. He was on his hands and knees, and was just crawling stealthily away towards a dark corner wherein some sacking and other packing materials were heaped. I stood quite still; and to my surprise, I saw him reach out his arm for a piece of the sacking, and attempt to toss it over his hindquarters, just as an elephant throws dust or straw over its back with its trunk.

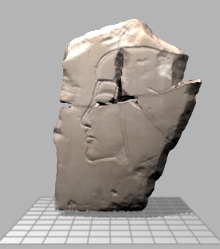

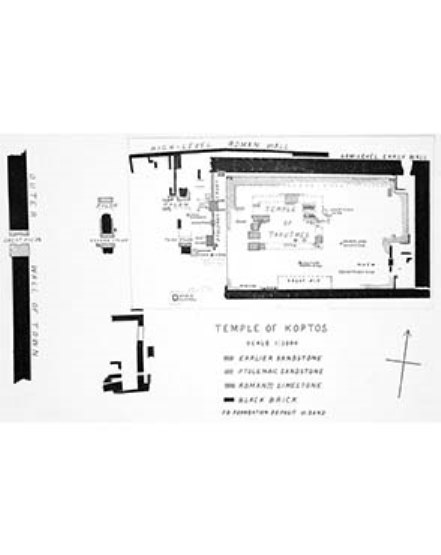

Petrie’s interest in the foundations of Egyptian civilization led him to the site of Koptos, with its multi-period temple dedicated to the god, Min. Over the years, Petrie trained dozens of archaeologists, including Howard Carter, who went on to discover the tomb of Tutankhamun and T.E. Lawrence. His students later described themselves as ‘Petrie’s Pups.’

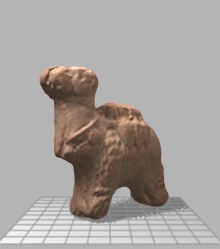

This head of the god Min-Amun may have come from Petrie's excavations at Koptos.

At Naqada, Petrie made a significant error, mistakenly attributing the early predynastic graves there to a ‘New Race’ entering Egypt after the Sixth Dynasty. He was forced subsequently to revise his dating.

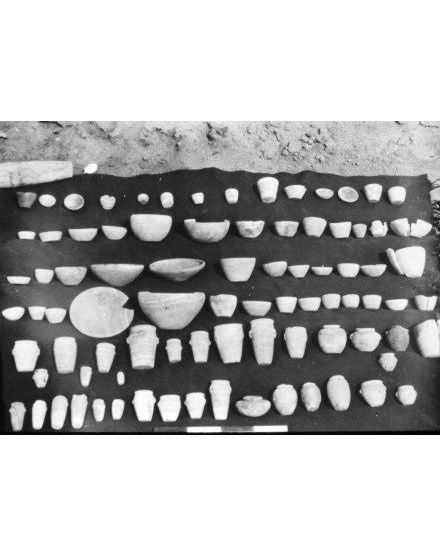

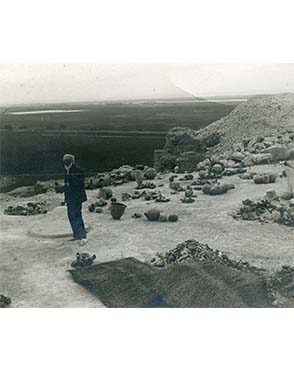

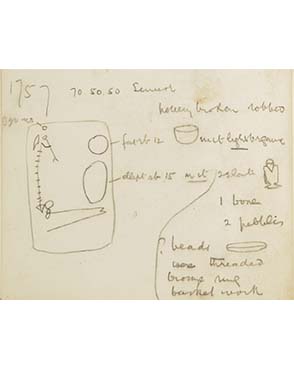

At the site of Naqada, Petrie tried to keep track of the excavations, writing in the final publication that "….nothing was recorded as exact in position unless I saw it unmoved, or with the cast of its bed in the earth….". The large amounts of material recovered also required Petrie to devise ground-breaking systematic methods of excavation and recording, particularly of pottery.

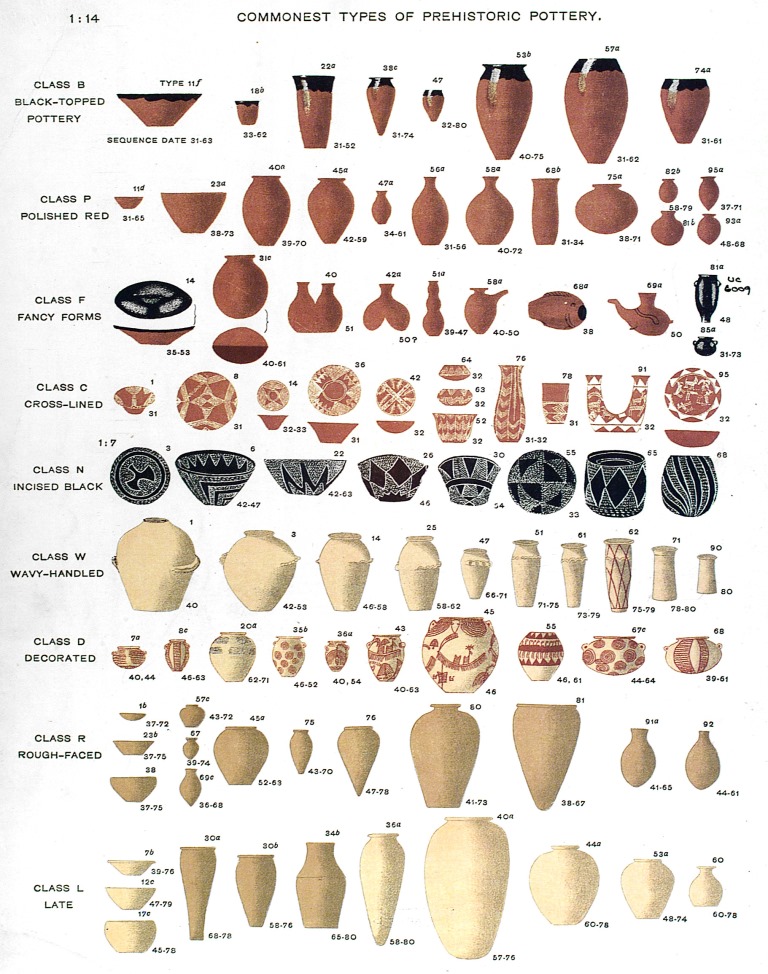

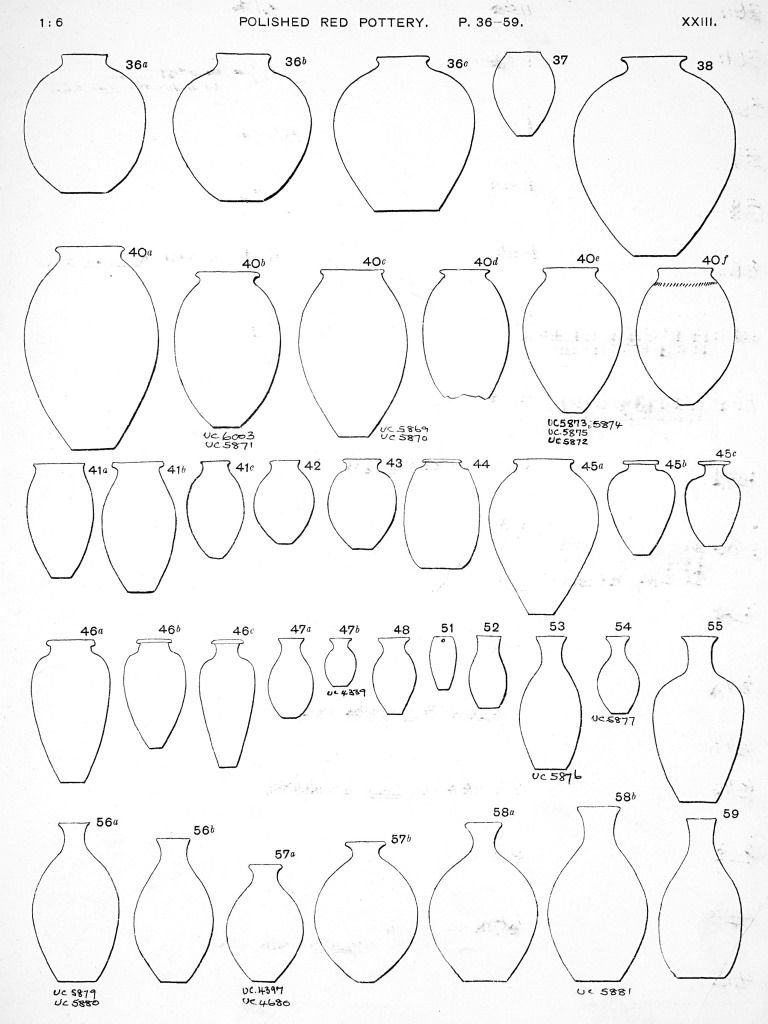

The drawings of the pottery constituted a corpus of the forms, arranged in a consecutive order of shapes. Thus was begun, from sheer necessity, the corpus system of denoting forms of all kinds of objects, and hence registering discoveries by corpus numbers – a system which revolutionises all archaeological work, and gives brief definitions in place of repeated drawings or long-winded descriptions.

True

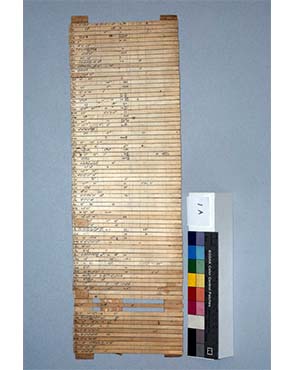

Examples of pottery types found at Naqada and Ballas. Petrie, Naqada and Ballas: 1895, pl. XXIII.

True

Petrie's notebook record for Grave 1757 at Naqada. Copyright Petrie Museum of Egyptian Archaeology.

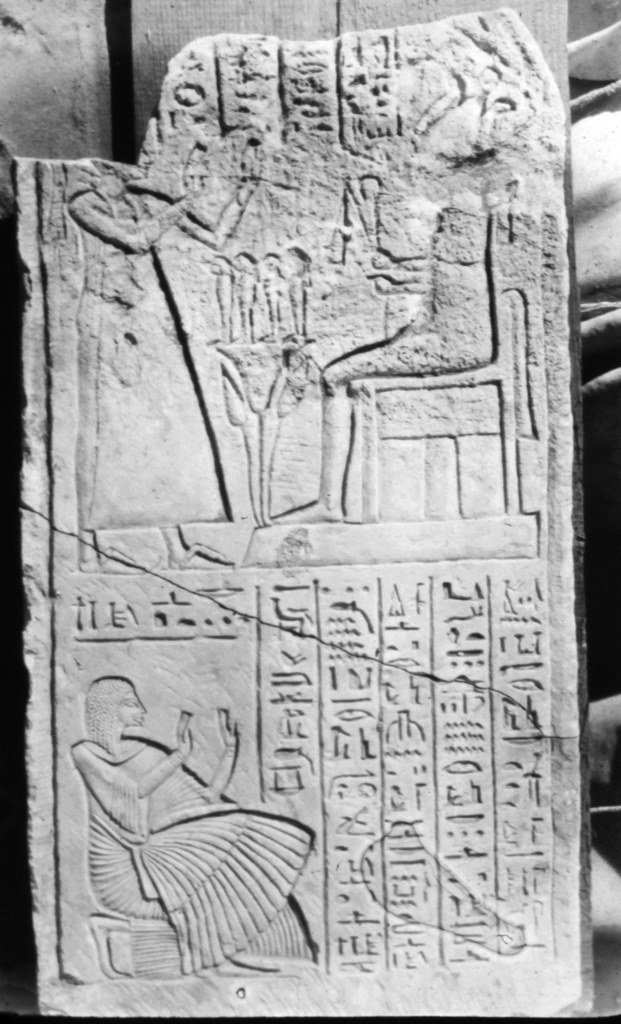

In the winter of 1895, Petrie began work at several temples in Thebes, deputizing Quibell to work at the Ramesseum. At the temple of Merenptah, Petrie discovered a stela which is still today the earliest known written reference to Israel.

“… For inscriptions, Spiegelberg was at hand, looking over all new material. He lay there copying for an afternoon, and came out saying, ‘there are names of various Syrian towns, and one which I do not know, Isirar.’ ‘Why, that is Israel,’ said I. ‘So it is, and won’t the reverends be pleased,’ was his reply.”

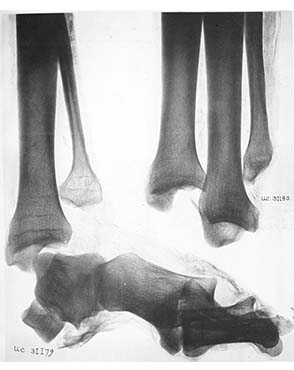

In 1896, Petrie turned his attention to the site of Deshasheh where he discovered decorated tombs.. Of particular interest were burials with examples of dismembered, defleshed bones which Petrie had X-rayed at UCL. These are the first examples of the use of X-rays in archaeology.

…no one has ever yet recorded fully any cemetery of the pyramid age; and all that I am doing is the only information that we possess about such burials. All that has been hitherto done has been more plundering to get show specimens.

Petrie met Hilda Urlin when she visited his annual exhibition and was immediately taken with her. After she eventually accepted his proposal she became a diligent and essential work partner and wife.

…it was entirely due to my wife that the resources of the British School were raised, to enable work to be carried on by me and our students; much of the facsimile drawing and plans were hers, and latterly the chief management, and paying, of hundreds of workmen.

This eye amulet was found on a mummy excavated at Dendereh.

Arguably Petrie’s greatest contribution was his development of Sequence Dating, the arrangement of predynastic pottery types into a chronological order which could then help date any undisturbed context in which that pottery was foundPetrie distinguished nine categories of pottery and, taking the frequency of their occurrence as an indication of chronological progression.

-

-

1903 — 1912

1903

-

1903-1912 Summary

Although enticed back to working for the Egypt Exploration Fund, Petrie again fell out with the management and set up his own British School of Archaeology in Egypt. This and the previous decade, mark Petrie's most active period in Egypt, not only for his own excavations but also for those he initiated for his students.

-

Petrie in his 50's

During 1905-6, Petrie set up his British School of Archaeology in Egypt, based at UCL. He organised a committee to manage the new School, which would fund his work.

The first excavations under Petrie's new British School of Archaeology in Egypt were back in the Delta, looking for Biblical connections, in particular relating to the Exodus.

Petrie also revisited some of the sites he had explored in the past, including Giza and Hawara.

In the Hawara cemetery we soon found more portraits, and altogether equally the output of twenty-four years before.

In 1911, Petrie began the first of two seasons on another early site, Tarkhan. At these excavations he first used formal printed index cards for recording the burials, although he continued to use notebooks as well.

-

-

1913 — 1922

1913

-

1913-1922 Summary

The catastrophic events of World War I caused a lull in Petrie’s excavations. This gave Petrie a chance to work on his publications, allowing him to produce a new journal, Ancient Egypt, to raise awareness of his work in Egypt. With a new family to support, Petrie arranged the sale of his collection, which he had used for teaching, to UCL and the museum subsequently opened to the public.

-

Petrie in his 60's

In 1907, Petrie offered to sell his collection to the university without profit, but it was not until 1913 that the funds were raised and the purchase finalised. Petrie hoped that this would mean that the collection could be properly displayed.

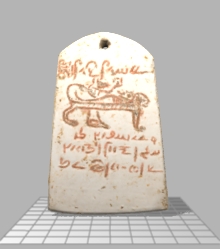

When World War I broke out, Petrie was unable to travel to Egypt to excavate. Instead, he turned his attention to writing up typologies of different classes of objects. These included publications on amulets (like the one shown here), scarabs, predynastic pottery and palettes, and tools and weapons. The typologies were based on excavated objects as well as examples Petrie had purchased. As early as his first trip to Egypt, he had been busy collecting objects to fill gaps in the excavated examples, as described in this account written by Howard Carter in 1891.

…there I met for the first time the famous archaeologist, Mr. W.M. Flinders Petrie, who was occupying his spare time by visiting native antiquity merchants in search of rare specimens to add to his collection of historical scarab-shaped seals – of which there is no better judge.

Petrie had an ambitious approach to his typologies, wanting to publish illustrated volumes that would list objects along with their dates and counterparts in other collections.

….my object has been to publish catalogue volumes, not only illustrating the series in each subject, but discussing the dates and links with other collections, so as to frame a library of Egyptian archaeology.

When the cessation in excavations due to the war meant that there was no annual exhibition of finds, Petrie opened the museum to the public for the first time. In the years immediately after the war, Petrie and his team returned to Egypt.

-

-

1923 — 1932

1923

-

1923-1932 Summary

Following restrictions to the entitlement of excavators to take artefacts out of Egypt which threatened his financial support from museums, Petrie decided to stop excavation in Egypt and turn his attention to Palestine.

-

Petrie in his 70's

On 25 July 1923, Petrie was knighted ‘for services to Egypt’ with no mention of his archaeological achievements. Petrie’s diary entry was succinct:'10.30 Buckingham Palace. Knighted. Back by 12.'

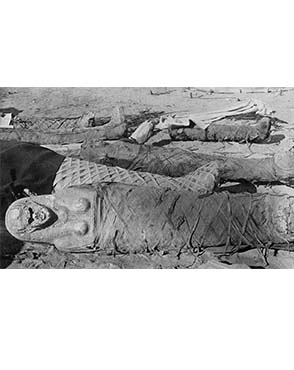

In 1923, Petrie underwent his last excavation in Egypt at Qau and Hemamieh, .He was particularly interested in the early predynastic burials at the site.

Petrie tried to link the sites he excavated in Palestine to places mentioned in the Bible, sometimes based on the names of the site. Tell Jemmeh, which he excavated in 1926-1927, he linked to Gerar, mentioned in Genesis.

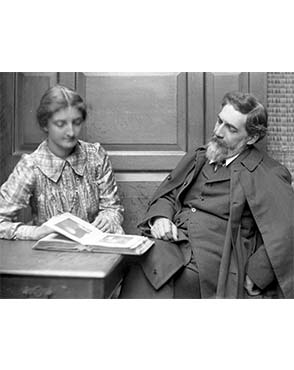

Back in England, Petrie continued some teaching but only on a limited scale. Petrie's biographer, Margaret Drower (1911-2012) recounted being one of Petrie's last students

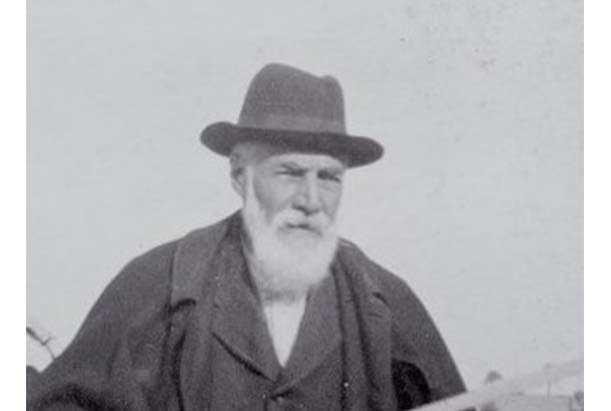

I have a memory of twinkling eyes, an unexpectedly high, light voice, bushy eyebrows and a patriarchal white beard.

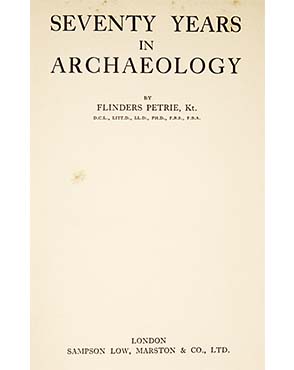

In 1931 Petrie published his autobiography, hoping that the book would interest others to archaeology. Petrie did not intend to discuss his private life, however he recounted his frustration in 1889 in dealings with Grébaut, the head of the antiquities service. Petrie was kept waiting for two days to see Grébaut, who was then distracted through the process. It was during that season at Hawara that the tomb of Horwedja was found.

...It was a fearful swoop to lose all the finest things, but I doubted if I should get better results by haggling over a quantity of other boxes, and losing some days more in this wretched unbusinesslike way.

-

-

1933 — 1942

1933

-

1933-1942 Summary

In these final years, Petrie retired as professor and he and Hilda left England and moved to Palestine. One success in this period was the subsequent housing of his Palestinian collection at UCLDespite numerous setbacks, he was determined to continue excavations but the outbreak of World War II brought any chance of this to a close. Petrie then focussed on finishing publications although ill health eventually left him too weak to continue. He died in Jerusalem in July 1942.

-

Petrie in his 80's

In autumn 1932, Petrie had announced his intention to retire from UCL in 1933 and, at 80 years old, he returned to dig at ‘Ajjul. Petrie’s last days in England were surprisingly bland, his diary entry simply read: “Clearing. Vict 14.0 Paris 22.0”

In 1935, Petrie’s catalogue of funerary shabti figures appeared. This drew on the impressive 650 examples in the museum collection. The publication also included useful information on the provenance of some of the figures.

Of recent years a large number of figures have been found at Thebes, which are evidently from a family cemetery…Scattered ones have come through dealers to the British Museum, and at Thebes I bought about forty.

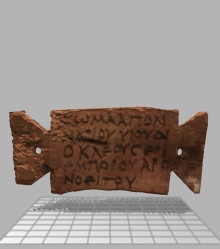

Next of Petrie’s catalogues of the museum collection to appear was a double volume in 1937, ‘The Funerary Furniture of Egypt and Stone and Metal Vases’. In the first part, he catalogued some 653 objects in the collection, which included the wooden name tags shown here.

In Roman times the mummies were often sent to be buried at some distance, and it was needful to identify them amid a boatload. For this purpose a small wooden label was tied on, stating usually the name and parentage, and sometimes the age and the place of residence.

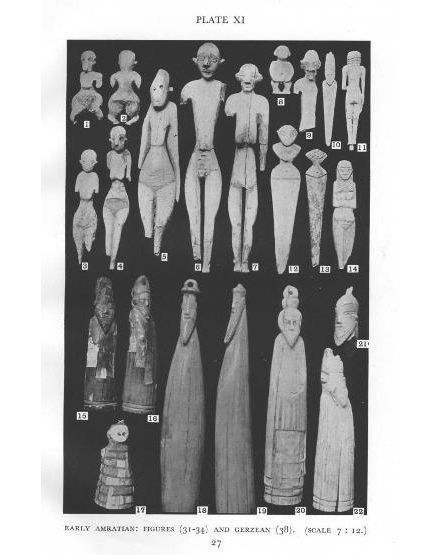

Without excavations going ahead, Petrie continued to focus on his publications. He mentions the volume ‘Making of Egypt’, in which he turned back to discussions of early Egypt. One plate featured the ivory figure shown here.

I am still getting on with finishing up books which are in hand. 'The Architecture' and 'Making of Egypt' are done, the 'Science of Egypt' is at the printers, 'Gaza V' is nearly ready, only Mammy is finishing some drawings. Two or three books are nearly ready. So I am pretty well clearing the decks before the old ship goes down.

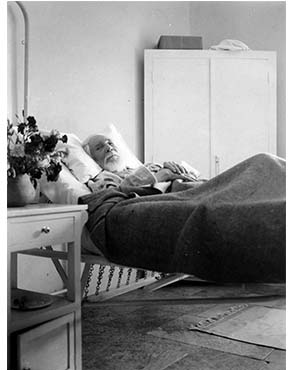

In October 1940, a serious bout of malaria left Petrie hospitalised. He remained in hospital until his death, 28 July 1942. Mortimer Wheeler, who happened to be in Egypt, heard that Petrie was gravely ill and drove to Jerusalem to see him.

His mind was running even faster than was its wont, as though it had a great distance still to cover before the approaching end. In the course of ten minutes it ranged without pause over a wide variety of matters, from the copper implements of Mesopotamia to the lethal incidence of malarial mosquito at Gaza.

Let there be no regrets, now that this life is past, For earth, and friends, and work have all been sweet to me – And labour garnered safe has laid the ages clear That all may plainly see what none had thought before.

-

Click or drag the timeline to move faster

-

1853

-

1863

-

1873

-

1883

-

1893

-

1903

-

1913

-

1923

-

1933