Loading...

From Egypt to the World

Today, it is strictly illegal to take ancient objects out of Egypt. In Petrie's time, the authorities in Egypt did allow excavators to bring back a proportion of the objects which were distributed to museums around the world. Here's the story of the objects.

Drag anywhere to explore

Click/tap on an image for more details

-

Arrival

The objects arrive in England

0

-

The objects arrive in England

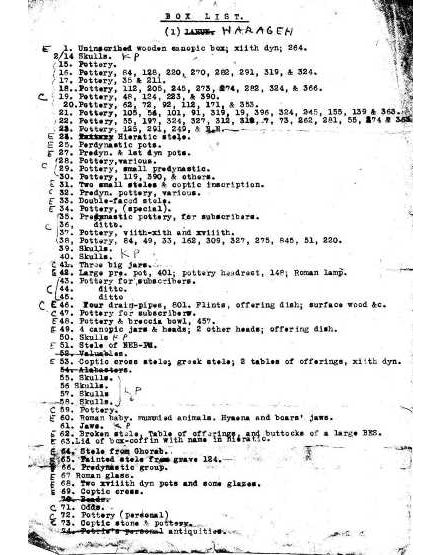

The boxes of ancient objects and field documentation might take some time to reach England. In 1883, for example, Petrie arrived back in London on 17 July but it was not until the end of August that the boxes of objects arrived. As the list of objects from the 1914 excavations at Harageh shows, the boxes of objects, often over 100 in total, would need to be unpacked. Care would be needed for the fragile objects like the cartonnage foot cover, so the process was slow. As Petrie wrote in 1891:

On June 15 I was back in London and took a small house for three months for unpacking and work at Bromley, near our own.

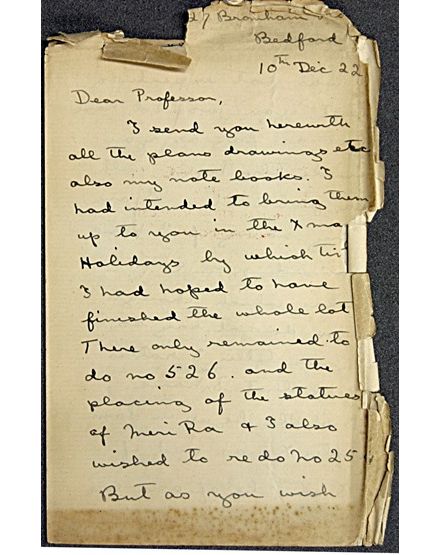

Team members were expected to work on their field notebooks after the season and give them to Petrie to help write up the final publication. In December 1922, H.G.C. Hynes, who worked with Petrie at Sedment wrote:

I send you herewith all the plans drawings etc also my note books. I had intended to bring them up to you in the Xmas Holidays by which time I had hope to have finished the whole lot….

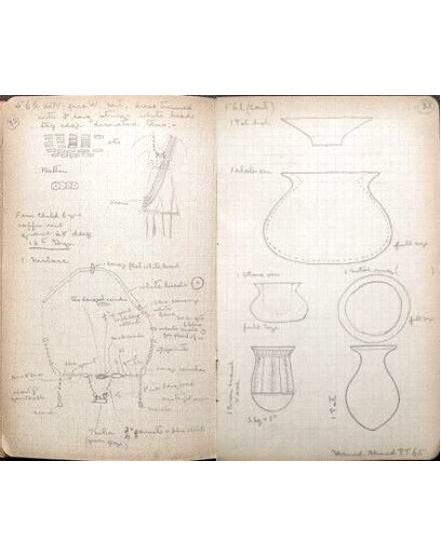

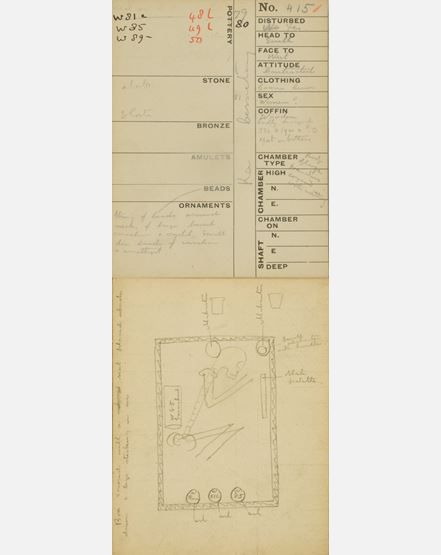

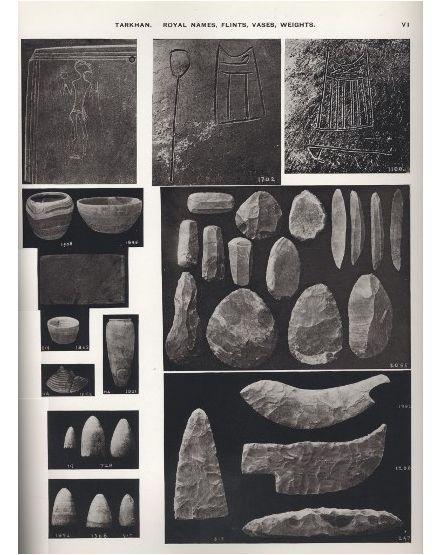

Other types of documentation were collated such as the printed cards Petrie began using to record burials at Tarkhan in 1912. These 'tomb cards' would have been filled out by team members during the dig and contained important information and sketches which helped in the preparation of the publication.

These results were all tallied with the register-cards, and the cards were then dated and arranged in groups of each period apart.

As well as administrative tasks, Petrie also undertook further photography and drawing of objects and plans. In 1889, after a season at Gurob and Kahun, he wrote:

In England I was back by June 28, and there was the work of plotting out the plans, drawing objects….and writing up the account….

-

-

Publication

Spreading the word

0

-

Spreading the word

From the very beginning of his work in Egypt, Petrie was committed to publishing the work of the season. Museums and individual subscribers to Petrie's excavations received a copy of the latest volume on his work, which was also available for purchase. For Petrie, the most important part of the publication was the plates, with their drawings, plans and photographs.

…the main structure of a book on any descriptive science is its plates, and the text is to show the meaning and relation of the facts already expressed by form. The plates, therefore, are the first thing to prepare; and when they are complete it is time to put in words the conclusions which have been reached.

Despite the abundance of drawings and photographs in the publications, Petrie prided himself on the speed at which they were produced.

By March 16, 1900, we left, and were in London on the 24th. I pushed on with the sixty-seven plates as quickly as I could, and had them in the plate printers’ hands by April 18, wrote the text and passed the proof of index June 22. Thus seven months from beginning work the full publication of results was ready for the opening of the exhibition. When Dr. King came from the Museum to see the things, he remarked: ‘I suppose you will be publishing these some day.’ ‘The volume is before you,’ was the reply.

Petrie’s publications are often criticised today for lacking detail by modern standards. In his publication 'Methods and Aims in Archaeology', he commented that ‘To describe every grave separately in detail means a callous disregard of students and reader, as such a mass of undigested material cannot be used.’ On the other hand, his narrative nature of describing the work seems almost more like a blog, as this excerpt from Memphis I shows:

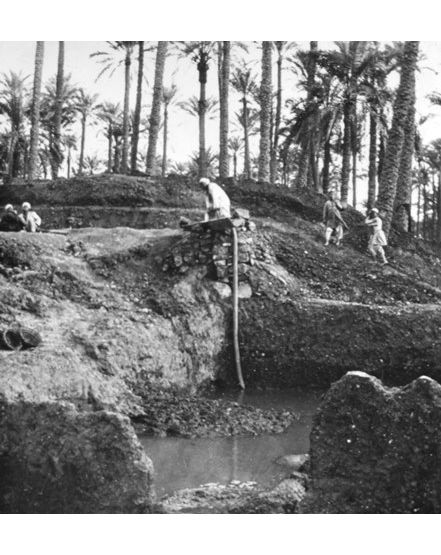

As we hope to be for many years on the site during the spring months (minor excavations elsewhere will occupy the winters), it was needful to build quarters raised well above the damp soil. Mr. Ward and Herr Schuler accordingly went there on Jan. 3 to begin building, and I followed on Jan. 26; before the middle of February our quarters were finished amid the rain, mud, and fogs which abound at that time of year. Our excavations started at the end of January, and went on till the first week of May.

Publicity about the excavations was important for generating subscriptions. Newspaper articles on the excavations were published both during and after the season. Although it seems incredible to us today, Petrie circulated his irreplaceable excavation notebooks around to colleagues and family, including to Amelia Edwards who used them for this purpose. Petrie was happy to have others promote his work, as this letter written to his friend Flaxman Spurrell in 1885 indicates.

…I am only too glad if anyone will relieve me of making anything public…Finding, no-one else will do, or scarcely anyone; publishing, many will do.

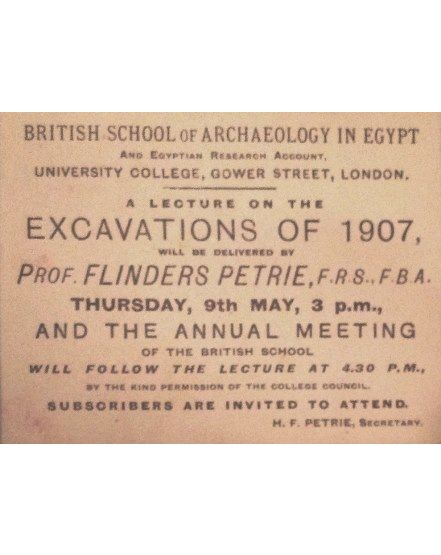

Annual meetings and reports gave subscribers a summary of the season’s work and the costs of the excavation. As Hilda Petrie made clear in the reports, efforts were made to show that the money was wisely spent.

…subscriptions or donations to the E.R.A. go direct to the excavations, as there are no expenses of office or secretary; the clerical work of correspondence and keeping the books is done by ourselves without cost to the Society.

Both Petrie and his wife Hilda were in demand for lectures to the public and professional organizations, as well as at conferences. The talks were illustrated with lantern slides and sometimes even actual objects. A widely dispersed network of local groups and honorary secretaries affiliated with the British School of Archaeology in Egypt also promoted Petrie's excavations and Egyptology in general. Petrie, however, was clear about his priorities.

Out of sight out of mind, and I never expect to bulk so much in the public mind when silent in Egypt as when playing showman in London. But I am not working for that end. So far as my own credit is concerned I look mostly to the production of a series of volumes, each of which shall be incapable of being altogether superseded, and which will remain for decades to come – perhaps centuries .

-

-

Exhibition

Objects on display

0

-

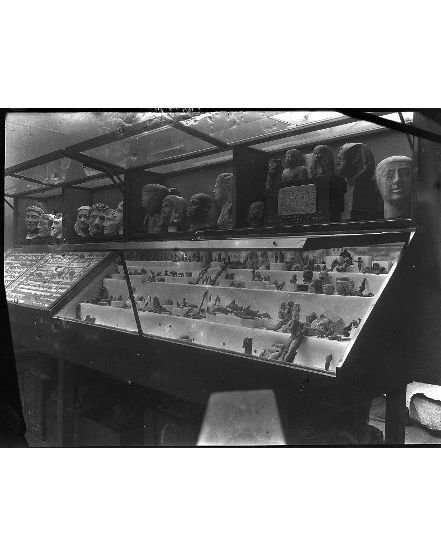

The objects on display

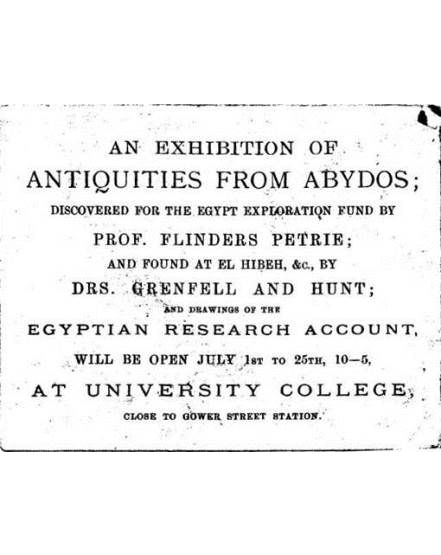

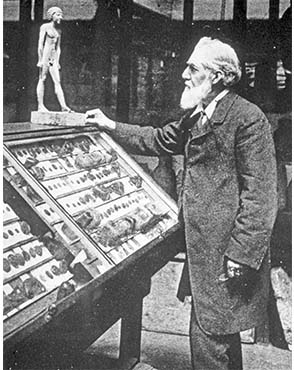

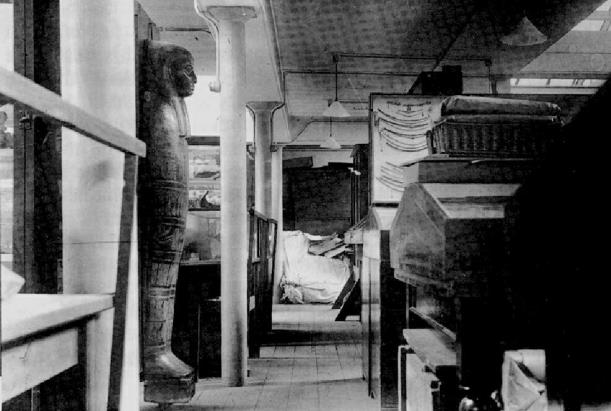

Petrie organized an annual exhibition in London of the objects brought back from that year's excavations. The exhibitions, like the one pictured here showing mummies excavated at Hawara, were good publicity for the excavations and offered a chance to raise funds. Importantly, museums and institutions who had sponsored the excavations also had an opportunity to review the finds and make suggestions for their collections. Petrie wrote about how the exhibitions started:

I had written to Poole [Honorary Secretary of the Egypt Exploration Fund] saying that a room should be obtained for exhibition; but all that was done was to agree on a shed at the back of a dealer’s garden. This was utterly impossible, so I went to the Royal Archaeological Institute, then in Oxford Mansions, and go the loan of their room. This led to my continuing to exhibit in that building until I was housed at University College.

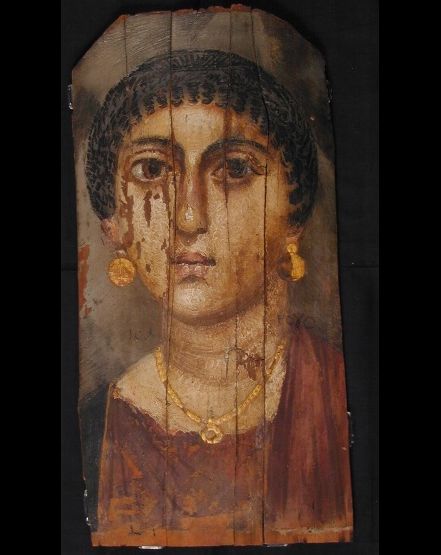

Preparation of the displays was time consuming. For damaged or fragile objects, conservation work might have to be carried out before the exhibition. There was also a question of how best to display the objects, such as the beautiful painted mummy portraits. Petrie recounted his work to display the portraits for the 1888 exhibition of finds from Hawara at the Egyptian Hall:

I had written to my father to get forty plain broad oak frames suitable for the portraits. In a fortnight I managed with Spurrell and Riley to get all unpacked, and to mount and hang the portraits. With three colours of card at hand, I laid each portrait on the cards to see which harmonized best, and then quickly ripped out a mount with a penknife and framed it, little thinking that those mounts would be retained for over forty years at the National Gallery.

Work on the exhibition did not always run as smoothly as planned. This letter dated to 5 July records a visit to Petrie’s 1909 exhibition of objects from Memphis by a Danish Egyptologist, Valdemar Schmidt, on behalf of the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek Museum in Copenhagen:

The Petrie exhibition opened at 10 am. I arrived punctually. He had been at it for five days, still has a ‘bad cold’, but recovering. He was busy affixing the labels.

Petrie relied on his friend, Riley, for help with the exhibitions. Petrie's first interest in coins was inspired by his visits to Riley's shop as a child. Riley’s help with the exhibitions continued until he passed away after the Naqada season in 1895, when objects like this comb were on display.

…when I began exhibiting antiquities in London he became my door-keeper and was my right hand in all the work. He revelled in the new discoveries, and used to show people round, enthusiastically.

Petrie noted that the annual exhibitions cost him £60-80 for rent and door-keeping, so he charged one shilling for entrance. Cards were printed announcing the exhibition. These were given to friends, colleagues and sponsors announcing the event. A letter to Petrie’s colleague, Francis Llewellyn Griffith, written in 1898 by the aunt of Griffith’s first wife, describes her visit to the exhibition.

Many thanks for the Petrie card….I made use of mine one day and made straight for the rooms, which with the help of a Beadle I at last reached….

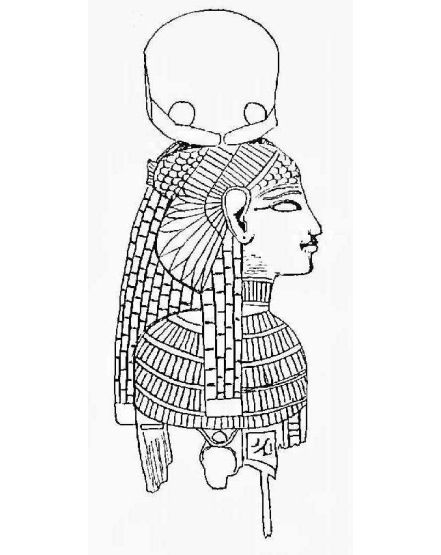

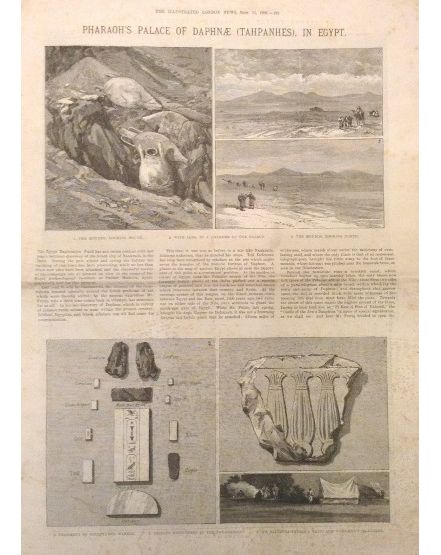

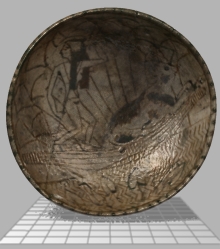

Publicity for the exhibitions was also important and the exhibitions often featured in publications such as the Illustrated London News. The ILN article on the exhibition held at Oxford Mansions from Sept 15-Oct 11 in 1890 illustrated drawings of objects from Gurob and Lahun, including the two shown here. The bowl was described in the article.

The glazed pottery of the Egyptians was sometimes painted with figure-subjects, though hitherto such have been rarely met with. Some examples, which were found broken, have been here repaired with good result. The bowl (8) with a girl poling a boat, in which is a calf, is a well-drawn subject.

As well as objects, there was at least one occasion when a model of the monuments were constructed for the exhibition. Just as with the setting up of the displays, students were drafted in to help, as Petrie noted regarding the 1906 exhibition of the season which included excavations in Sinai.

I had a model of the hill of Onias and temple site, also of the Hyksos fort, for the exhibition. At this, Duncan helped, and a new student Ernest Mackay, who was twenty years later to dig up the oldest civilisation of India.

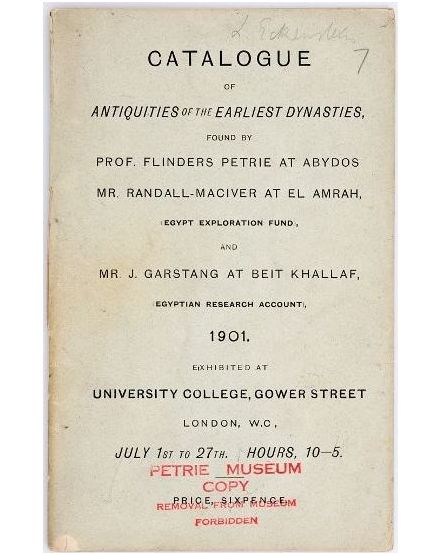

Catalogues were printed and handed out to representatives of the subscribing museums who used them to check off objects of particular interest. These would help Petrie in deciding the final distribution of objects. Objects like amulets and pottery were sometimes not specified in the requests but were often amongst the objects distributed.

I am herewith enclosing marked catalogue as requested, and trust the choice of objects I have made will meet with your favourable consideration when the time comes for distributing them.

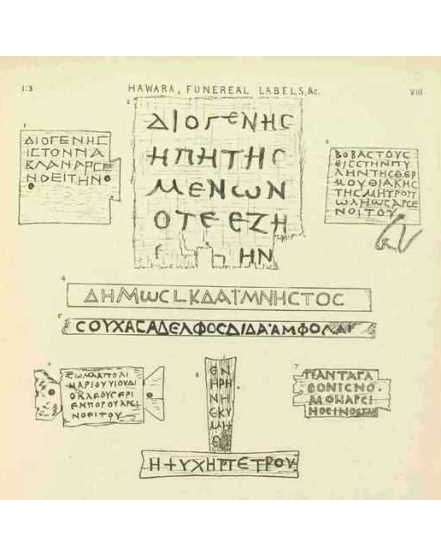

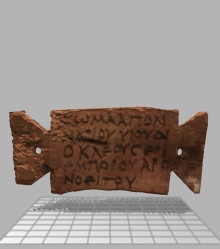

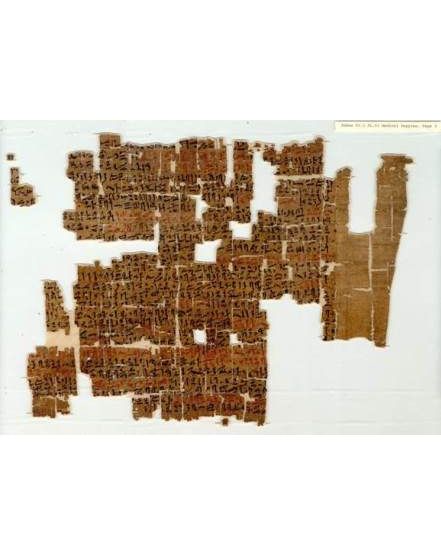

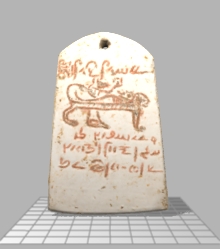

Objects were sometimes also displayed at other exhibitions, or ‘conversazione’, held by learned societies, often scientific organizations, such as the Museum of the Royal College of Surgeons. From the objects from the 1890 excavations at Lahun and Gurob, which included the name tag shown here, the Royal Society chose to display the famous medical papyri from Lahun, also illustrated.

The conversazione of the Royal Society, held on Wednesday evening, was very largely attended by eminent men of science, and by many of the leaders of the medical profession, as well as by a distinguished array of guests of social, literary and political distinction….The exhibits were numerous and exceedingly interesting.

This name tag was from Petrie's excavations at Hawara.

See full object record

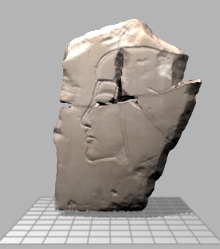

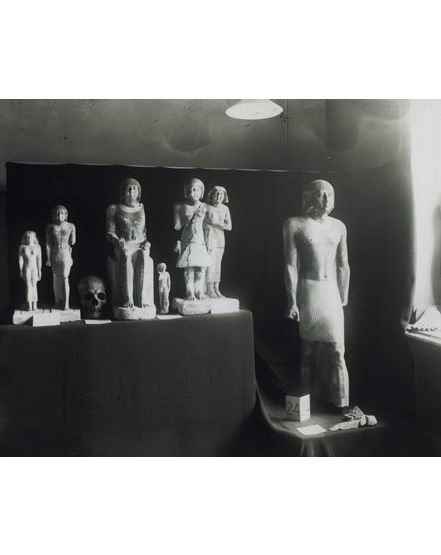

In 1897, Petrie's exhibition of finds from the Old Kingdom cemetery at Deshasheh coincided with a ‘conversazione’ held at UCL. This offered a chance for demonstrations and displays across the departments. As the photograph shows, the exhibition that year included the impressive statue of Nenkheftka (now in the British Museum).

All the museums, theatres, lecture rooms and libraries, as well as the Flaxman Gallery and Slade School were thrown open, and in many of the laboratories interesting demonstrations of recent advances in applied science were attended by large numbers of guests…from Egypt also came the antiquities exhibited by Professor Flinders Petrie.

-

-

Distribution

Object distribution

0

-

Distributing objects

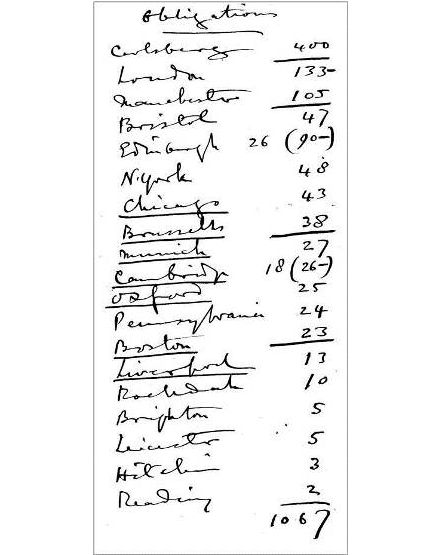

In Petrie's time, with permission from the authorities in Egypt, museums and supporting institutions would receive objects that matched the contributions they had made to the excavations. This list shows the contributors to the excavations of 1910 along with the amounts given. The list reflects the international distribution of objects which included museums in Copenhagen in Denmark, Pennsylvania in the US, and Brighton and Hitchin in the UK.

I would suggest the Ny Carlsberg Foundation signs up for…£400 for Petrie. It will anyhow be the biggest contribution.

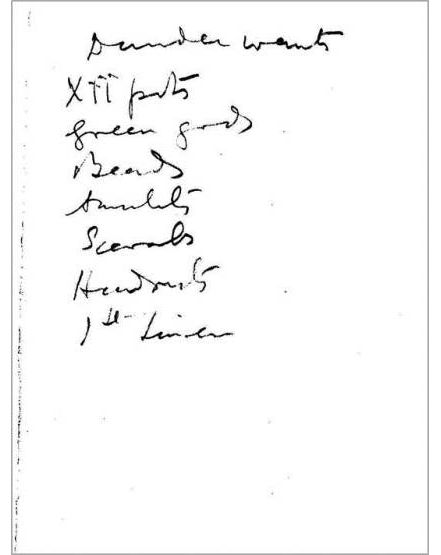

There was no guarantee that museums would receive their requested objects, although efforts were made to try to match requests as this list of objects wanted by Dundee indicates.

Dundee wants XII pots Green gods Beads Amulets Scarabs Headrests 1st Linen

Sometimes there were negotiations over the objects as this excerpt from a letter sent by one museum to Petrie indicates. The decorated bowl mentioned is perhaps one like the one shown here.

Have just returned from Holland hence delay in replying to your letter of 29th July. Having already several of the alabaster vases of the types you have we shall prefer to have the Blue glazed Bowl with figures + the basalt head or bust about 6” high of the XXVI dynasty.

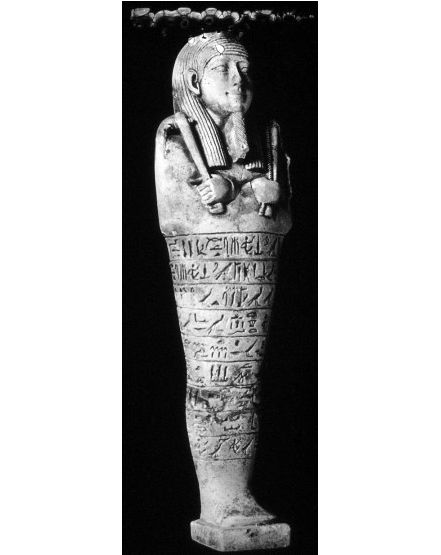

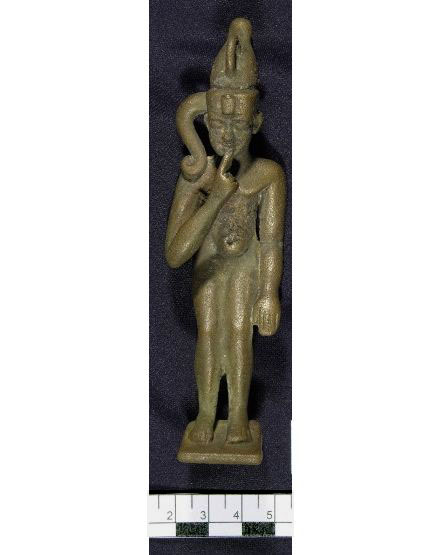

Objects were packed and shipped to the museums by post, rail or sea as necessary. Fragile objects, such as the figure shown here, would need careful attention. Included in the package was a list and information about the objects.

I beg to acknowledge the safe arrival of 4 cases and 1 small one. Please accept my thanks for the specimens, which have all been chequed by the list, and have arrived in good condition….

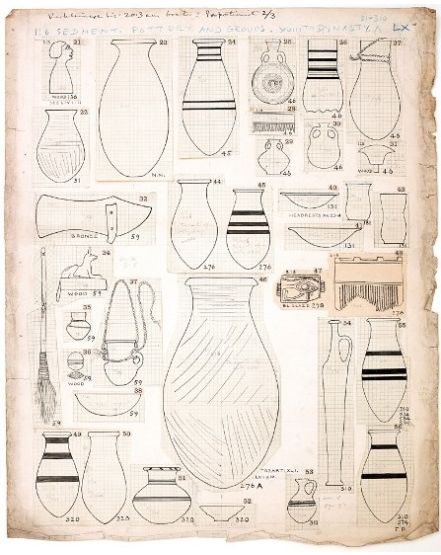

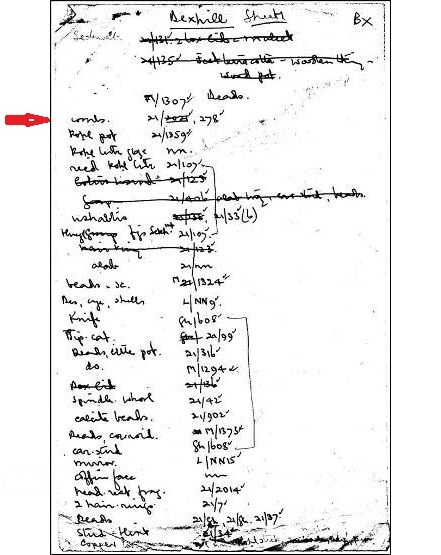

This sheet lists the objects from the excavations at Sedment and Gurob that were sent to Bexhill Museum in 1921. Brief descriptions of the objects are given on the left, and details of the tombs or contexts where they had been found are given on the right. The list also shows that changes were made. Page 1 of the list shows the comb was noted. The cartonnage mask was listed on the second page. The list included a number of objects:

combs kohl pot ....reed kohl stick....ushabtis.....knife....tip-cat.....spindle whorl....calcite beads....Beads, cowroid....ear-stud...mirror....coffin face.....head rest frag....2 hair rings....

True

List of objects given to Bexhill Museum in the 1921 distribution. From the Petrie Museum archive.

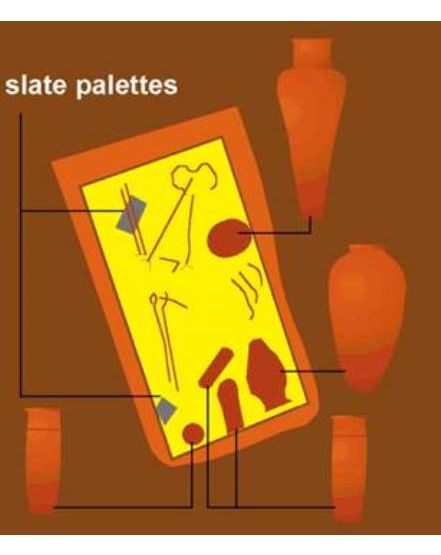

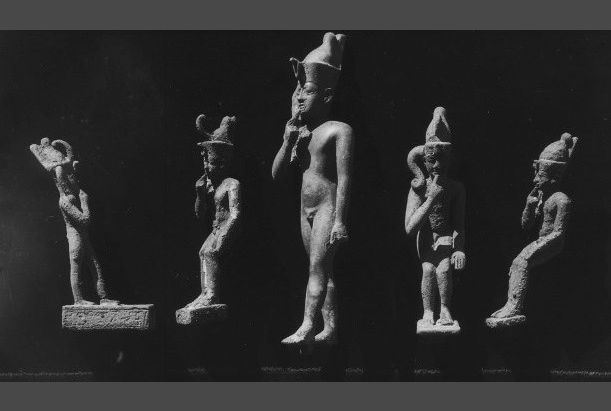

In contrast, Petrie claimed to have tried to keep groups of objects together, focusing on those he thought most important. Notably, the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford was able to build up a significant collection of objects from early Egypt, similar to those in the Petrie Museum shown here, after the British Museum refused statues of Min from Koptos on the grounds that they were ‘unhistoric’.

…those figures being there led next year to the offer of the whole of the great type collection of the prehistoric Egyptian civilisation from Naqada going also to Oxford, and making that the standard place for the early Egyptian art. That in turn led to the Hierakonpolis sculptures following there.

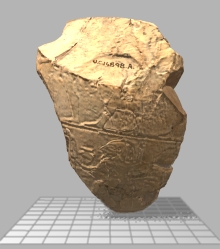

As a result of the distribution system, objects from the same site and, surprisingly, sometimes even the same burial were distributed to different museums. Objects ended up as far away as Japan, South Africa and America. This palette came from a burial which contained another palette and five pottery vessels. The whereabouts of the other objects, if they did leave Egypt, is not known. The shabti funerary figures are both part of groups split between several museums.

It has been a bitter sight to me, everything being so split up in England that no really representative collection of my results could be kept together.

Although the distribution of ancient objects was permitted by authorities in Egypt in Petrie’s time, today it is understood that objects should stay in their country of origin and it is strictly illegal to take objects out of Egypt. We must be very grateful for the objects currently in museum collections and safeguard them carefully.

To raid the whole of past ages, and put all that we think effective into museums, is only to ensure that such things will perish in course of time. A museum is only a temporary place. There is not one storehouse in the world that has lasted a couple of thousand years.

-

-

The Petrie Collection

0

-

The Petrie Museum

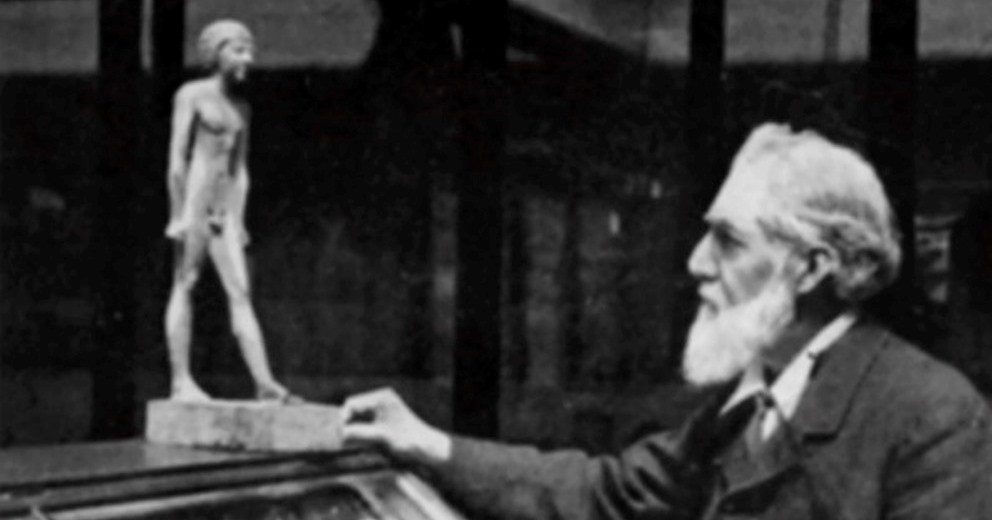

The Petrie Museum began with the collection of Amelia Edwards

The collection now at University College was first started by Miss Amelia B. Edwards on her visit to Egypt in 1874. When her intention took form to bequeath a foundation for Egyptology in London, she obtained many specimens for that purpose from the work carried on in Egypt, nearly all from my excavations….

This Petrie supplemented with objects from his excavations and also with objects he had purchased.

Meanwhile since 1881 I had been purchasing objects in Egypt, and keep a share of what was found in my private excavations.

Petrie seems to have called the museum simply 'The Egyptian Museum, University College'. For him, the museum had different aims to most other museums and the objects often reflect those priorities. For that reason, objects that were for example broken or damaged could also be of great importance.

The purpose of this collection differs from that of the National and County collections. It is not intended to attract and interest general visitors, but is for study and teaching purposes. The branches of the subject, and the nature of the specimens, have been selected with this in view. It is therefore supplementary to the other and greater collections, giving in certain lines much more details than is shown elsewhere.

From the time Petrie became professor, objects were used in teaching. He emphasized the importance of studying all aspects of ancient Egypt, including history, language, religion, materials, industries and art. On the study of art, Petrie commented:

Not only should the details of the various periods be clearly separated, but also the various schools or local centres of art, the products of any one of which have a strong likeness throughout varying ages….To clear up these local schools, the material must be our main guide….

Petrie also stressed the value of creating typologies of objects so students could study their changes over time. One example of this would be Petrie’s work on the funerary shabti figures, called by him ushabtis.

The funerary figures or ushabtis have been occasionally published, but not comparative series of them is arranged, to show their historical changes. We need a systematic catalogue of all the ushabtis known, such a corpus would throw great light on them.

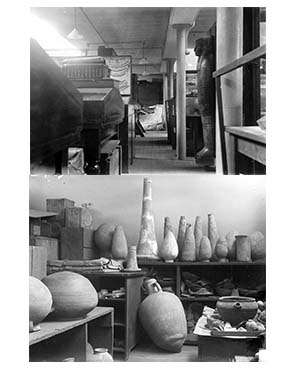

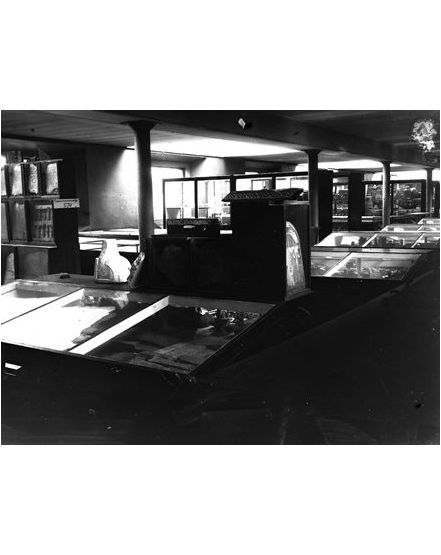

Display cases contained many objects but, as Petrie wrote, ‘The first consideration was the amount and direction of the lighting'. The display of plaster mummy head covers included the example shown here.

The room containing it occupies the top floor of one wing of University College, 120 feet long and 50 feet wide. About a fifth of this space is occupied by the Egyptian library, workroom and stores, and spaces too dark for exhibition. The remainder is filled with glass cases as closely as may be.

Petrie offered to sell his collection to the university and, after several years of frustrating uncertainty, the collection was finally purchased by UCL in 1913. The flyer produced for the fundraising appeal described the collection as ‘the best teaching Collection in this country’. The first donor was the noted chemist, archaeologist and benefactor Sir Robert Mond, who contributed £1,000. Some of Mond’s objects subsequently came into the Petrie Museum collection in the 1950’s.

At last things moved, and some contributions were given, mainly from Robert Mond…

In 1915, World War I disrupted Petrie's excavations. With no objects for the annual exhibition, Petrie decided to open the museum to the public for a month and published a handbook to the collection. This was the historic first time this important collection was made publicly accessible.

The War made an entire break of all my work in Egypt for five years….those dreary years, short of food and coal (we never had any butter, and could not use a fireless study) and in the perpetual uncertainty of the future. The College collection arrangement had to be completed, and by June 1915 I was able to make it a public exhibition with a handbook.

-

Click or drag the timeline to move faster

-

Arrival

-

Publication

-

Exhibition

-

Distribution

-

The Petrie Collection