Scanning the brain to find answers

1 January 1970

Science never stands still. There's a constant stream of new discoveries and new questions - and dementia research is no exception. Dr Tim Shakespeare is an Alzheimer's Research UK Research Fellow at UCL. He's studying a condition called posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), a rare form of Alzheimer's disease which was only identified in the 1980s.

Posterior Cortical Atrophy (PCA)

"There's still a lot we don't know about PCA," he says. "We have lots of questions. We do know it's usually caused by the same changes in the brain that happen in Alzheimer's disease.

"But with typical Alzheimer's, the memory centres of the brain are affected, particularly structures called the hippocampi. PCA on the other hand affects the back of the brain, which deals with visual information from the eyes. So those who have it might initially have problems with seeing where and what things are, rather than their memory."

People with PCA tend to show symptoms earlier, in their 50s and 60s - but nobody knows why. It's also not known exactly how many people actually have it. As it's such a new condition, awareness is low, meaning that some people who actually have PCA might have been diagnosed with something else - or not have a diagnosis at all.

Dr Shakespeare and his team

Dr Shakespeare works in a team at UCL that is trying to find answers to these questions. Every year, volunteers with PCA come to UCL to take psychological tests and have their brains scanned. This means that researchers can see what's changed in their brains since the previous year.

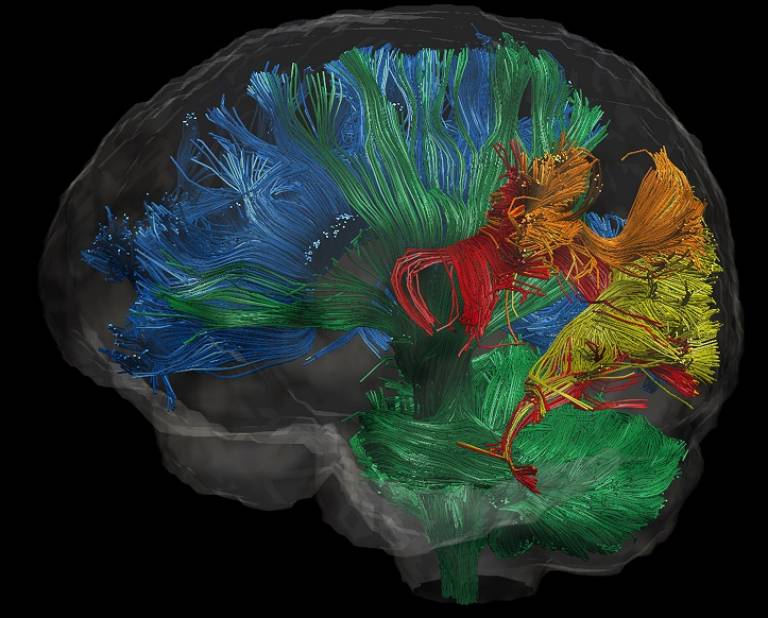

"Our outer layer of brain is the grey matter" he explains. "This layer contains the cell bodies of neurons - the brain cells which allow our brains to work. But between these cell bodies is white matter. This is what connects up our brain - the brain's cabling, if you like.

"New brain imaging techniques allow us to study these connections and see what they're doing - for example, if some parts of the brain aren't so well connected to others, or if the disease has changed the connections in any way. We're looking to see if these connections are related to the way the disease spreads through the brain over time."

The team at UCL is also leading a group of researchers from centres around the world looking for genes which might play a part in the disease. They are investigating whether a particular gene could make it more likely that a person will develop PCA, and visual symptoms, rather than the more common memory symptoms. Understanding this could give them clues as to why certain parts of the brain are vulnerable to the disease in some people but not others..

Armed with information from all these projects - along with the psychological tests which examine the symptoms in detail - Shakespeare and his fellow researchers can try to work out which changes in the brain affect which symptoms, and how much variation there is between individuals.

"Hopefully, we'll gain an understanding of exactly what's going on with

PCA," he says. "If we can say these particular changes in the brain

usually lead to these particular symptoms, and progress over a certain

length of time, that would mean we could give patients much better

answers to their questions about how the disease will affect them, so

that they can plan for the future."

More awareness of PCA and

other rarer forms of dementia would help researchers and patients

enormously. Better knowledge means more patients could get an accurate

diagnosis more quickly, while those who are already diagnosed would get

better treatment. That's why Shakespeare has designed an online course

in those rare forms.

"We run support groups for people with PCA,

and they were telling us that there is very little awareness of their

condition - they were always having to explain it," says Shakespeare.

"The course focuses on a different form of dementia each week. It

features people with dementia and their carers talking about the

condition, experts, new research, and explains the challenges are."

The

course "The Many Faces of Dementia" which launched in March 16, is

aimed at anyone with an interest in dementia. You don't have to have any

medical knowledge to take it. 10,000 people have registered for it so

far, including nurses at care homes and academics from other global

institutions

Others who have already signed up, says Shakespeare,

are people who are living with dementia themselves, their relatives,

and those who work with dementia patients, such as GPs and occupational

therapists.

And none of this would be possible without the

public's donations, which is why Shakespeare is excited about the

Dementia Research Institute, funded partly with donations from the

carrier bag tax.

"There's already a massive breadth of expertise

at UCL, from the people who work on molecules in the brain to those who

study how relationships are affected by dementia," he says. "Hopefully

the Institute will help us attract more really good researchers and

build on existing expertise so we can work faster towards the goals of

better treatments and better care.

Close

Close