Phase I: 8th January – 7th June 2019

Phase II: 25th September 2019 - 13 December 2019

Edward Allington, 1988. © the artist’s estate. Photo: Sakata Eiichiro

Edward Allington, Snail from the Necropolis of Hope, 1983. © the artist’s estate. Photo: Mary Hinkley

Edward Allington, Euridike (1986), UCL Art Museum, 2012 © Edward Allington & Heini Schneebeli

Edward Allington and Jo Volley, No title (detail), 2017 © Jo Volley and the artist’s estate

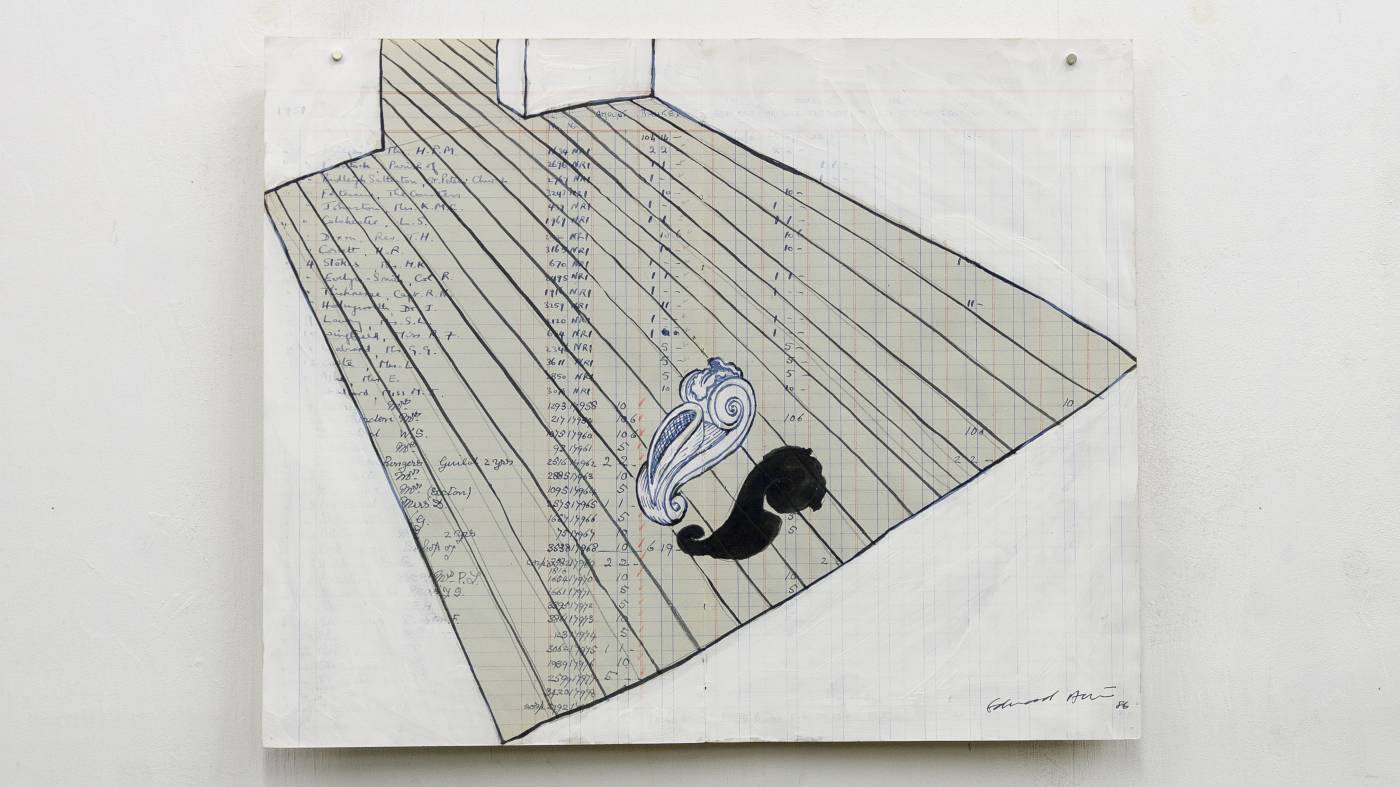

Edward Allington, Upright and Feeling Form, 1986 © the artist’s estate. Photo: Harry Allington-Wood

Edward Allington and Edward Woodman, Decorative Forms Over The World, Egypt (detail), 1991. © Edward Woodman and the artist’s estate. Photo: Edward Woodman

Edward Allington and Jo Volley, No title, 2017 © the artist’s estate and Jo Volley. Photo: Mary Hinkley

This celebration of British artist Edward Allington (1951-2017) at UCL Art Museum, launched UCL's Year of Sculpture 2019 earlier this year.

Sculptures, photographs, drawings, antique ledgers, motorbike parts and toy dinosaurs are part of the exhibition, exploring Allington’s concerns and ambitions for sculpture, as well as his composite persona as artist, writer, educator, collector and motorcyclist. The public programme has included interpretations through dance with a youth group from The Place and dance students from University of East London.

Find out more about Edward Allington and his work below.

UCL Art Museum wishes to thank Thalia and Harry Allington-Wood, Megan Piper, Jo Volley and Gary Woodley in realising Edward Allington: In pursuit of sculpture, curated by Dr Andrea Fredericksen and Dr Nina Pearlman.

This is part of UCL Art Collections’ commitment to interdisciplinary research-based and exhibitions-led collaborations. For more information or expressions of interest to collaborate contact museums@ucl.ac.uk

See more of Edward Allington at the Henry Moore Institute:

Exhibition: Edward Allington: Things Unsaid 25 Oct – 19 January, focusing on the artist’s larger sculpture works.

Conference: Sense – Perception: Sculpture, Drawing and Influence of Classicism, Henry Moore Studios and Gardens, 12 October 2019, Henry Moore Institute 29 November 2019

- Edward Allington: In pursuit of sculpture - exhibition

Edward Allington: In pursuit of sculpture presents a selection of the acclaimed sculptor’s smaller works, cohabiting with the university's historical collections in a traditional Print Room setting.

Allington was fascinated by the classical worlds of Greece and Rome, particularly the hold they have on our imagination and how they continue to shape our physical environment. His preoccupation with timely questions about authenticity, origins and truth evolved from his practice as a sculptor, researcher, writer and teacher. He was not nostalgic, but rather recognised in classical sculpture radical qualities that fuelled his practice. He noted that sculpture was based on principles and processes of reproduction – such as casting, and that often our encounter with it is through souvenirs or heavily restored artefacts in museums. Most classical sculptures are themselves copies – Roman copies in stone of Greek sculptures in bronze that are lost and only known to us through descriptions by Greek scholars.

In Allington’s words ‘I realised that in culture itself it is impossible to prove that one level is more important than any other. As an artist it would be irresponsible to omit what I began to see as the larger part of culture. I had to learn and understand not only ‘high’ art but also ‘low’ art.’ As such a preoccupation with kitsch infused Allington’s work in the 1980s where the Dionysian energies of exuberance, opulence and excess were at play in his ‘cornucopia’ sculptures. Snail from the Necropolis of Hope (1983) shown in the exhibition represents this body of work in which plentiful plastic fruits, insects, frogs or vases spill out of decorative shells or horn-like forms.

While paintings generally have a wall as their backdrop – wherever that wall may be, the backdrop for sculpture changes. A recurring theme for Allington was sculpture’s capacity to subvert its surroundings and for sculpture’s capacity to change as a result of its placing. He maintained that everywhere there is a space in which sculptures cohabit and interact with other things and that most sculptures are made with ideal settings in mind yet are more likely to exist in storage, a home, an institution or a photograph. This led him to explore the union of site-sculpture-photography through a longstanding collaboration with Edward Woodman. This included Decorative Forms Over the World, a series that was ongoing since the mid-1980s and is featured in the exhibition. Allington and Woodman travelled with an illusionistic drawing – a scroll based on an architectural corbel – and photographed it in different locations and situations. More recently, Heini Schneebeli photographed Allington’s small bronzes which he placed amidst collections in the museums of UCL.

Edward Allington, We are time (1985), photographed in UCL Art Museum, 2012 by Heini Schneebeli © Heini Schneebeli & the artist's estate

Allington was equally interested in the power of memory and addressed the states of materiality and illusion with playfulness and humour. This is evident in his drawings, which were an integral part of his practice, as well as in Three Japanese Measuring Devices (2016) where three small sculptures are concealed within an antique ledger becoming invisible when the ledger is closed, or Suitcase: Lost World (2010) where a plentiful stream of plastic dinosaurs spills out of a suitcase. These works prompt reflection on the significance of the visible and physical presence of the object, as opposed to our memory of it.

Edward Allington, Three Japanese Measuring Devices, 2016, antique ledger book, ledger paper, ink, emulsion, MDF and bronze, photo: Sam Roberts © the artist’s estate

- Antique ledgers were among the many objects Allington collected, alongside plastic replicas of classical architecture, motorbike models and actual motorbike parts, selections of which feature in the exhibition. All of these collectables became infused with sculpture and embodied alternating status as disposable copy, sculpture fragment, or drawing surface. Sheets from the ledgers that carried tracings of everyday life became the surfaces upon which Allington inscribed architectural spaces. Into these imaginary spaces he introduced oblique projections of sculptural forms that fused natural, architectural and mechanical orders, ultimately forging what became his signature style.

Edward Allington and Jo Volley, no title, scanned drawing scaled up and printed on vinyl, installed UCL courtyard, 2017, photo: Mary Hinkley©the artist’s estate and Jo Volley

The exhibition is book-ended by one of Allington’s earliest works as a student of ceramics and his final public work in the UK: a collaboration with artist and fellow Slade Professor, Jo Volley. Their drawing has been scaled-up to be 7.5m high to wrap around a pop-up structure in the courtyard of UCL. The work features classical columns, as well as drawing and building instruments, which are overlaid on a chart depicting the growth of UCL in its first 100 years. Inscribed with the UCL motto Cuncti adsint meritaeque expectent praemia palmae (Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward) the piece reflects upon the university’s development.

To read more about Edward Allington - sculpture and photography visit our blog.

[1] ‘Edward Allington interviewed by Stuart Morgan 1983’ in Edward Allington:: In pursuit of savage luxury, Midland Group Nottingham, 1984, p.26.

- About the artist

Edward Allington on his 1970 Harley Davidson XR750 TT, The Sammy Miller Museum, UK, 2014 © the artist’s estate

Edward Allington (1951-2017) was born in Cumbria. He studied at Lancaster College of Art (1968-1971), Central School of Art and Design (1971-1974) and at the Royal College of Art (1983-1984). Associated with New British Sculpture, Allington’s work was included in the group exhibition ‘Objects and Sculpture’ at the Institute of Contemporary Arts in 1981 and ‘The Sculpture Show’ at The Hayward Gallery in 1983, and he exhibited widely in America, Japan and throughout Europe.

Allington was the winner of the John Moores Liverpool Exhibition Prize in 1989 and received a fine art award to work at the British School at Rome in 1997. He is represented in major public, private and corporate collections, including Arts Council England, Tate, Henry Moore Institute, Victoria and Albert Museum and The British Museum.

Allington lived and worked in London and was Professor of Sculpture at the Slade School of Fine Art until he died on 2017 at the age of 66.

- The Slade sculpture prize

From the establishment of the Slade School of Fine Art in 1871 prizes were awarded to students in a range of categories, including sculpture. However, unlike paintings and drawings, the prizes in sculpture were not retained by the School. Archival records denote a phantom collection of prize-winning works of sculpture that is lost.

The first prize for the year 1889-1890 was awarded to a female artist we know little about, noted in the College records as S Rosamund Praeger. Recent research has indicated that prizes were awarded consistently till 1906, then again in 1948, with the final prize awarded in 1969. More research is required to identify this phantom collection of prize-winning works by students, many of them women.

Phyllida Barlow CBE RA was recipient of the Summer Competition prize for sculpture in 1964-65 and again in 1965-66 in the category of Free Work.

Other artists include, repeat prize winners Paul de Monchaux and Rosemary Young.

This is an ongoing research project connected to Spotlight on the Slade. The Sculpture Prize has also been a focus of new research undertaken in 2019 by a group of post-graduate UCL Museum Studies students.

- Year of Sculpture 2019

This exhibition is part of UCL's year-long programme exploring what sculpture means today. Find out more

Close

Close