The public support a central role for judges

8 February 2023

The latest Constitution Unit research reveals overwhelming public backing for judges to retain a central role in the UK’s constitutional structure.

Most people think judges should remain at the heart of the UK’s constitutional system: for holding politicians to the rules, adjudicating on disputes between government and parliament, and protecting human rights. Support for the European Court of Human Rights is somewhat lower than support for the UK courts. Even so, a clear majority think that it should play a part too.

These are central findings from the latest tranche of survey results to be released from the Unit’s Democracy in the UK after Brexit research project. They come from a survey conducted in late summer, just before Liz Truss took over as Prime Minister.

Some of the key findings are summarised today by Joshua Rozenberg.

Key points

Most people think the courts should play a strong role in the UK’s governing system: in ensuring that politicians operate within the rules; in adjudicating between government and parliament where there are disputes over authority; and in and upholding human rights.

Support for a strong role for the courts in upholding rights is higher if the source of those rights is not specified. If rights are specified as those defined in the Human Rights Act or the European Convention on Human Rights, that support diminishes somewhat, suggesting that some people have a negative view of these instruments. But clear majority support for the courts’ role nevertheless remains.

Similarly, support is lower if the court in question is specified as the European Court of Human Rights than if it is left as ‘the courts in the UK’ or simply ‘the courts’. Nevertheless, a majority think that even the European Court of Human Rights should be able either to declare a law passed by the UK parliament as null and void, or to require parliament to think again.

The project and the survey

YouGov interviewed 4,105 respondents between 26 August and 5 September 2022 as part of the second population survey of the Democracy in the UK after Brexit project. The survey closed just before Liz Truss was announced as the new leader of the Conservative Party.

The full report on the results of this survey, among the most detailed of its kind conducted in the UK, will be published next month. The survey investigated public attitudes on a range of issues including the role of democratic institutions, standards in public life and the state of democracy. More details about the survey can be found here.

The Democracy in the UK after Brexit project is funded by the Economic and Social Research Council through its Governance after Brexit programme. It is led by Professor Alan Renwick, working with Professor Meg Russell and Professor Ben Lauderdale.

Questions & results

Note: What follows is an excerpt from our forthcoming report on the survey findings, which will be released in early March. The report’s authors are Alan Renwick, Ben Lauderdale, Meg Russell, and James Cleaver.

One area where our 2021 survey results prompted particular discussion was on the role of judges. It has commonly been assumed that the public – in line with some tabloid headlines – are hostile to judges having a role in decision-making on politically controversial matters. In fact, we found that not to be the case: trust was much higher in the court system than in politicians; and most people wanted strong roles for the courts in protecting human rights and adjudicating on the limits of government powers (see Report 1, pp. 2–3 and 10–11). Given that these findings were widely viewed as surprising, we wanted to explore the issues further. Were such preferences stable? Were they robust to changes in question wording? Were they contingent on factors that we had not asked about?

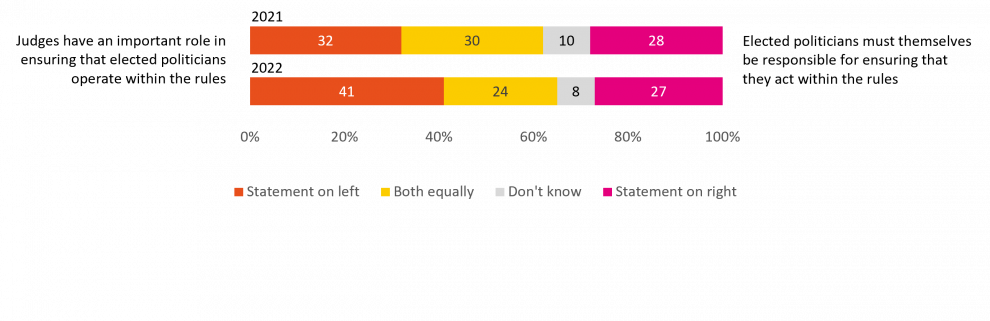

The question on trust, which was included in both surveys, indicated that the 2021 findings were not one-offs: the 2022 survey found that trust in the courts remained almost unchanged over the period. Another repeated question, on the role of judges in ensuring that elected politicians operate within the rules, found that support for that role had strengthened.

Question: Which comes closer to your view?

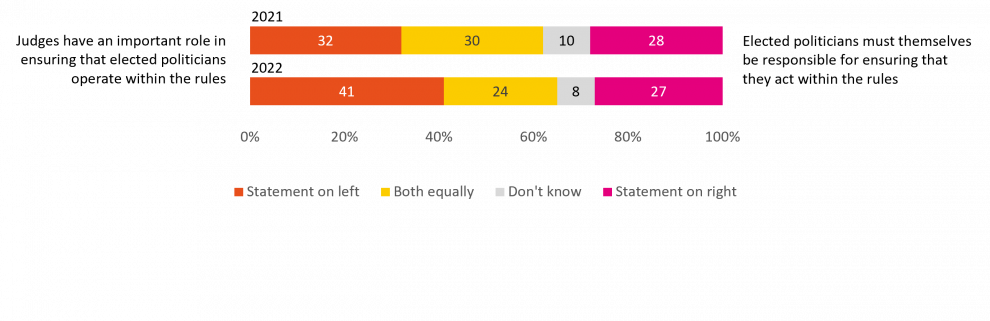

The 2021 survey included a question about how a dispute over government powers should be resolved. Half of the respondents saw exactly the same question in 2022. Views remained substantially the same: faced with three options, by far the largest group of respondents thought the matter should be settled by judges.

Question: Please imagine there is a dispute over whether the government has the legal authority to decide a particular matter on its own or whether it needs parliament’s approval. How should this dispute be settled?

Different respondents saw slightly different wordings, which were reported in our previous report (Report 1, p. 10–11). The patterns remained very similar in 2022.

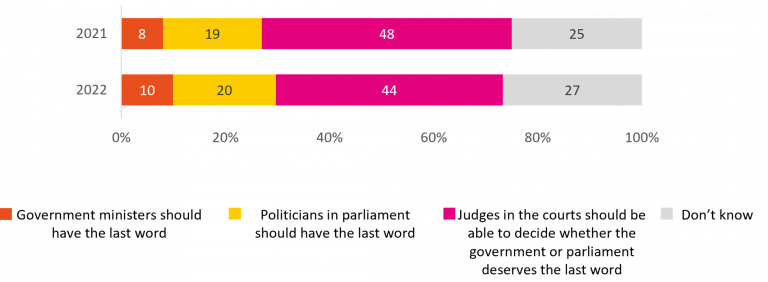

We were concerned that the wording of this question might have created an inadvertent bias in favour of judges: the question presented a choice about the powers of government and parliament; respondents who were unsure might have selected the third option in order to leave someone else – judges – to decide. The remaining half of the respondents therefore saw a different version of the question in 2022. In fact, support for the judges’ role remained the same, adding to confidence that this was a real preference.

Question: Please imagine there is a dispute over whether the government has the legal authority to decide a particular matter on its own or whether it needs parliament’s approval. How should this dispute be settled?

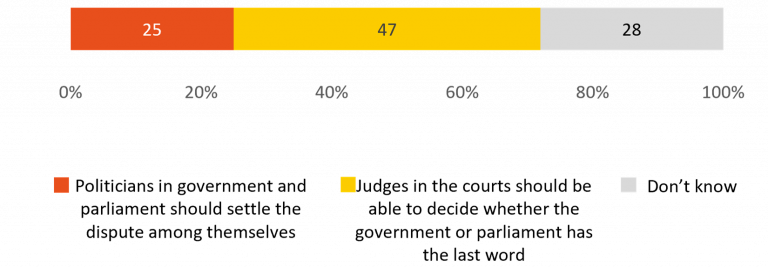

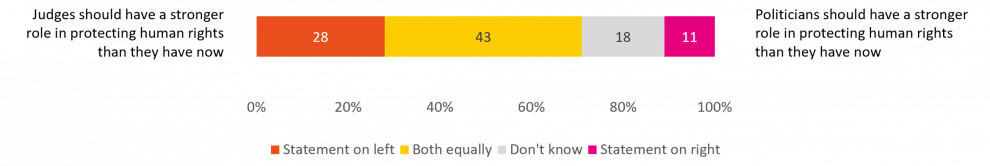

The 2022 survey included a new question that sought to sum up views on the role of judges in protecting human rights. Though some prominent voices have argued that powers in this area should return to politicians, few respondents agreed; well over twice as many thought that the judges’ role should in fact be strengthened. The largest group said they agreed or disagreed with both statements equally, indicating that they wanted responsibilities to be shared across different actors – as is the case at present.

Question: Which comes closer to your view?

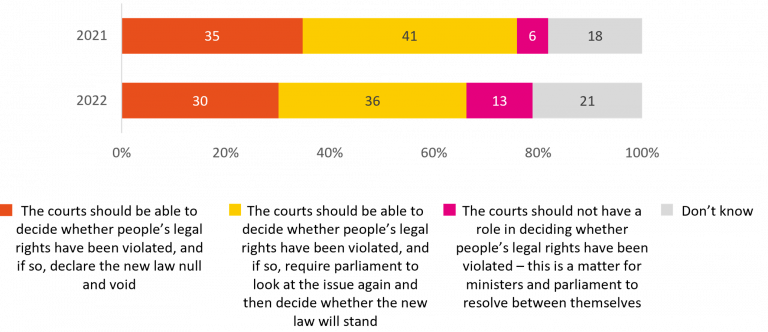

We also revisited a question from the 2021 survey that examined attitudes towards courts and human rights in more detail. The 2021 version of the question focused on whether people’s attitudes to judicial involvement were affected by which rights were under discussion. It found that there was some variation across rights: people were more comfortable with the courts adjudicating on, for example, women’s rights to equal treatment in the workplace and pensioners’ rights to benefits than they were in relation to the rights of terror suspects to a fair trial or of refugees to stay in the UK. But the differences across these rights were small: in all cases, a substantial majority thought the courts should play a role; and around a third thought courts should be able to strike down laws that violated such rights – going beyond the courts’ current powers (see Report 1, pp. 10–11).

Some respondents in 2022 saw exactly the same question again. The overall patterns remained very similar, though support for the view that courts should have no role had on average grown somewhat.

Question: Please imagine the government has proposed a new law and parliament has approved it. Some people believe that this law violates [RIGHT]. Should the courts be able to decide whether people’s legal rights have been violated as claimed?

Each respondent saw one specific proposed right in place of ‘[RIGHT]’. The chart shows average responses across all of these.

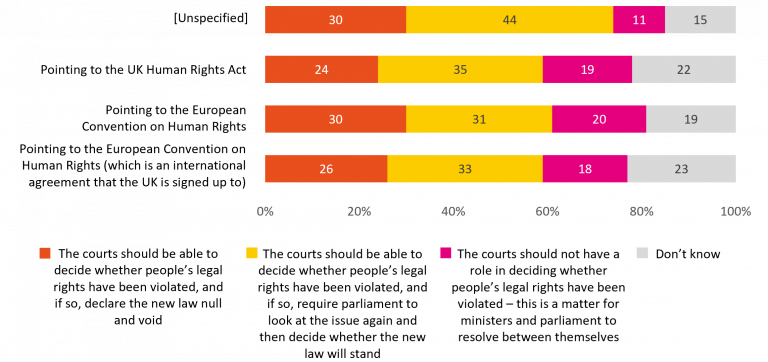

Most respondents to this question answered slightly altered versions of the question, designed to gauge two further possible influences upon people’s responses. First, we wanted to see whether specifying a particular legal origin of claimed rights – the UK Human Rights Act or the European Convention on Human Rights – made a difference. Second, we wanted to see whether specifying ‘the courts in the UK’ or ‘the European Court of Human Rights’ changed the responses. Given the tenor of public debate on the matter, we expected that support for a judicial role would be lower when the European Convention or European Court was mentioned.

On the first point, specifying a legal origin did reduce support for the courts having a role to a degree: the combined extent of the two categories on the left of the following chart diminished. Perhaps surprisingly, it did not matter whether the question specified the UK Human Rights Act or the European Convention on Human Rights: this may suggest that both have become associated in some people’s minds with unpopular court rulings. Given that most respondents would know little of the European Convention and might think it related to the European Union, we included a version that explained what it is, but this did not significantly change the results. The differences between these versions of the question and the original version, where the legal origin was unspecified, are noteworthy. Nevertheless, the main conclusion remains the same: substantial majorities thought the courts should retain an important role.

Question: Please imagine the government has proposed a new law and parliament has approved it. [ORIGIN] Some people believe that this law violates [RIGHT]. Should the courts be able to decide whether people’s legal rights have been violated as claimed?

Each respondent saw one specific proposed right in place of ‘[RIGHT]’. The chart shows average responses across all of these. In place of ‘[ORIGIN]’, respondents saw either no text – the ‘unspecified’ option below – or one of the phrases on the left of the chart.

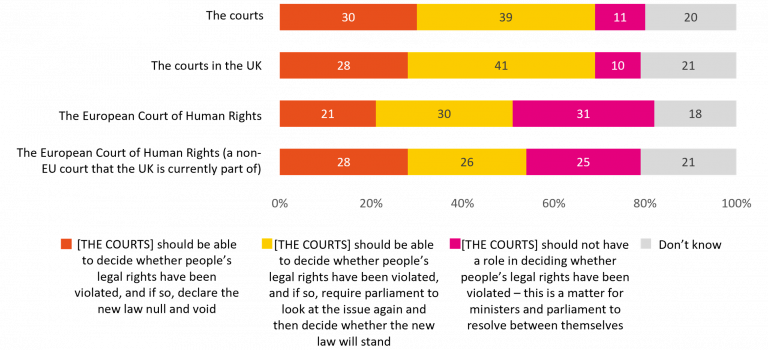

Meanwhile, specifying the European Court of Human Rights significantly reduced support for court action – though this effect was reduced when the question explained what this court is. Nevertheless, more than half the respondents thought that even the European Court of Human Rights should have a role, against fewer than a third who thought that it should not.

Question: Please imagine the government has proposed a new law and parliament has approved it. Some people believe that this law violates [RIGHT]. Should [THE COURTS] be able to decide whether people’s legal rights have been violated as claimed?

Each respondent saw one specific proposed right in place of ‘[RIGHT]’. The chart shows average responses across all of these. In place of ‘[THE COURTS]’ in the question and the response options, respondents saw either no text – the ‘unspecified’ option below – or one of the phrases on the left of the chart.

Read more about the Democracy in the UK after Brexit project

Further results from this survey:

- Majority of the public support House of Lords appointments reform

- The public want independent regulation of standards in politics

Close

Close