Disability, Design and Innovation MSc moves to its new home at UCL East in 2022. UCL Computer Science Professor and Academic Director of the GDI Hub, Cathy Holloway, explains more about the programme.

Cathy, please tell us what makes the Disability, Design and Innovation (DDI) MSc different?

A lot of disability courses are quite theoretical, or they are more clinically focused, looking at specifics like orthotics or prosthetics.

MSc DDI is different, it is an interdisciplinary programme that is about making the world more inclusive for disabled people through the process of innovation.

It brings together the different strands of disability, design and assistive technology. We think of disability innovation as being more than a product, service or policy – it’s a whole approach.

We train people in the Global Disability Innovation (GDI) Hub way of thinking about the complexities of disability inclusion.

What are the benefits of this Master’s programme being taught at the GDI Hub?

When people join the Disability, Design and Innovation MSc, they become part of the GDI Hub, which is putting its beliefs into action across the world.

We’ve now reached 26 million people through our GDI Hub initiatives.

We were responsible for ensuring the Tokyo 2020 Paralympic Games was screened free to Sub-Saharan African countries.

We’ve helped develop and test toolkits for the WHO to measure population health, and we’ve developed the Assistive Technology Impact Fund, which enables frontier technology solutions to be developed for people with disabilities in Africa.

We’re also the only WHO collaborated centre on assistive technology in the world. So when people join the Master’s programme, they become part of all of this.

Once you’re with us, you’re with us.

Two of our current Master’s students want to set up companies, and I’m helping them in my spare time. We’re a community. We help each other. We fall down together, and we get back up together.

Do you have a personal approach to succeeding in disability innovation?

I think you have to believe in the process, as once you understand this, you can apply it to anything. For some people, talking about ‘process’ doesn’t sound very innovative, but it is actually the best way to succeed.

I often tell my students about when I first started my career. I had a degree in Industrial Engineering Design, and I was living in the west of Ireland.

I managed to land one of the premier jobs in research and development with Medtronic, straight out of university. Friends of mine who were biomedical engineers were quite shocked that I’d managed this!

I remember the interview was full of very detailed questions, and I kept saying: ‘I don’t know the answers to these questions, but I would find the answers using this particular process’ or: ‘I would use these design skills to solve that problem.’ And I got the job.

If you’re confident in your background and you have a good skillset, you really can apply core skills to anything.

We don’t just teach design skills, we teach people how to be disability innovators – this includes knowledge of the global challenges in this space, and we have a GDI Hub method which builds on design thinking and inclusive innovation.

It is this - the GDI Hub method our students learn which they can then apply to everything from international development to product design. I’ve seen time and again how it works, and it works well.

How does the history of disability feed into the programme content?

If you want to do anything in the disability space, you need to know the history of disability. We cover this in the Future Global Technologies for Disability Development module.

There was a medical model of disability, which looked at disability as a body part not working, and the medical world would try to fix it. The idea was that either you could be fixed, or you couldn’t.

That model still persists in some countries and situations today, especially around mental health.

After this, the social model of disability came along, which said that you might have an impairment, but disability happens when the environment is not designed for you.

The classic example is a building. You might not be able to walk up steps, but if a building has level access, then you can enter, and you are not disabled from entering the building.

Moving from a medical model to a social model and then beyond a social model has been hard, and it has been political. Exclusion of any group of people is political.

Our disability innovators have to know the history and the politics to understand how to work with disabled people, disabled people's organisations to make the world a fairer place.

What are some of the barriers to developing innovations in the disability space?

Disability inclusion is complex, and poverty is directly interlinked with disability. Most people who are disabled are poor, and you’re more likely to be disabled if you’re poor.

Assistive technology like wheelchairs, hearing aids and glasses seem quite common in this country, but 90% of the people who need them globally don’t have access.

So even if you have the ability to design a new disability innovation, you need to consider if customers could afford it, how you would market it and if you can even gain access to the right people to do user testing.

Full systems thinking is needed - understanding procurement and policy, people’s ability and willingness to pay as well as the costs and benefits are all necessary to bring a new product to market.

New technology opens up opportunities for radically new ways for disabled people to interact with technology, however it also brings challenges for increasing or persisting existing stigma against disabled people.

Stigma is a huge issue for disabled people, but also for disability innovators. It is hard to get innovations funded.

How do you tackle this through the Disability, Design and Innovation MSc?

The programme content is underpinned by some important aspects of design thinking and research methods, which is a module delivered by our partners Loughborough University London (LUL).

This equips students with the skills to think through these complex problems, to better articulate the problems, and to clearly communicate the solutions they envisage.

Working directly with people with disabilities and innovators is also important to our students.

Last year, we had innovators from India and Kenya involved in the programme. They were developing assistive technology and needed help with specific research problems to help get their technologies to market.

Students had the opportunity to work on a variety of issues. Some did policy analysis to help influence the Kenyan government with better policies to help Braille readers gain access to written material; others created new products to help visually impaired people.

Students also have the opportunity to collaborate with companies and organisations in east London to help solve specific local problems or challenges in relation to disability innovation.

What other outside influences do students on the Master’s course benefit from?

We have a slogan of: ‘research, teach, practice’. We work with a lot of partners in different fields, and we try to expose our Master’s students to as much of this as possible.

We have partnerships with organisations big and small, from small charities in Kenya to the likes of UNICEF.

Many of our students work both with an academic partner and an industry or ecosystem partner for their dissertations too.

For example, this year we have students working with Google, Microsoft, MultiTech, the World Bank, the Asian Development Bank and UNICEF and the World Health Organisation (WHO).

You also collaborate with the London College of Fashion (LCF) for this Master’s programme – why is that?

They deliver a module on applied business and marketing strategy for disability development. A lot of people ask us why LCF delivers a business module – it doesn’t sound like an obvious choice!

But actually, getting fashion to people has a lot of similarities with getting assistive technologies out.

This is mainly because the populations are quite small. For a lot of assistive technologies – once you go beyond glasses and hearing aids – the number of possible customers drops quite significantly.

You get people with very bespoke needs, or you might have people who have multiple disabilities who need certain devices.

The populations that can make use of these devices might only be one or two thousand people.

Scaling a business model in these circumstances is quite difficult. This LCF module enables students to create business plans and marketing strategies, and every year we get brilliant feedback about it.

What kind of hands-on expertise in the field do the academics teaching this programme have?

A great example of this is Iain McKinnon, who teaches the Inclusive Design in Environments module. He’s also the co-director of the GDI Hub with me.

Iain was one of the people who led the inclusive design of the Queen Elizabeth Olympic Park, where the UCL East campus is now located.

He led on all the standards of how you make buildings accessible, and how you transform the site from sport events to non-sport events and make it inclusive the whole time.

He did that through a process with the Built Environment Access Panel who were a group of disabled people who had veto rights.

If they said any aspect of the plans were not accessible enough, then it would have to go back to the architects until it was good enough; but it wasn’t a fight, it was a conversation – a process of constant improvement.

Iain is currently in the process of extending his methodology on this built environment work to six cities across the world.

What do you teach on the programme?

My module is called Disability Interactions (previously Accessibility and Assistive Technology) and it’s about how people interact with technologies.

We start with the history of accessibility, looking at products that have been made such as keyboards. But keyboards don’t work for everybody, so we’ve made some small add-ons to try to retrofit accessibility.

Then accessibility became the law – you have to make products accessible, and websites must be accessible too. Despite this, of the majority of FTSE 100 companies still don’t have fully accessible websites for blind and visually impaired people.

So we also look at issues about how laws are not always implemented in the digital world.

We take this background further to explore the development of new types of interaction to help make digital technologies more inclusive, and some of my students have come up with some fantastic innovations.

Can you give an example?

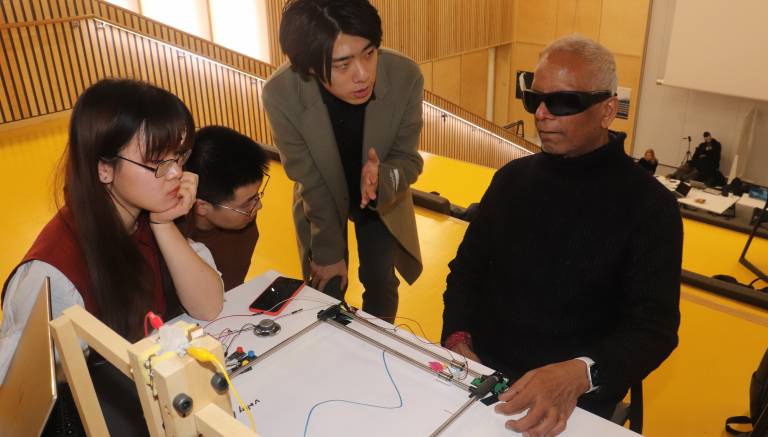

One of my student teams has made a device that uses shape memory alloy to allow blind people to draw.

It enables them to sketch using a pen that uses heat to make a raised surface, which can even be rubbed out too.

This innovation came from working directly with schools in India, and learning that blind children wanted to find a way to express themselves.

This is also an example of an idea for which a business case is impossible – there’s no way to make it scalable to the population, because the population of people who could use this technology is too small.

So what we’re doing at the moment is working with MBA students from the London Business School to develop other applications for the underlying technology.

It looks like the automotive industry and the airline industry are very interested in the technology.

So the business case would be to sell the technology to another industry, with the agreement that they make a certain number of these devices every year for distribution to blind and visually impaired people.

What kind of jobs do graduates of this programme go on to?

UN organisations are currently expanding their accessibility and inclusion teams, so they are always coming to us asking if any of our students want to apply for their jobs.

Government-level jobs across the world are expanding globally in this area too, and Asian countries and the Asian Development Bank are particularly active in this field at the moment.

We’ve had a few students who have become entrepreneurs, launching their own companies in the disability innovation field.

A lot of the big technology companies are expanding their accessibility remits, so some of our graduates have gone on to work for the likes of Google and Facebook. Some of our students have stayed on to do PhDs or to work for the GDI Hub.

Close

Close