Visual

Rosie Lowndes at The Greycoat Hospital

Here are a series of pictures I took, based around the witch Circe. I wanted to do a 20s, art-deco take on the classic Greek tale of Circe and Odysseus, as the 20’s took a lot of fashion inspiration from ancient Greece; long, flowing silhouettes, without discernible waistlines, and draped necklines, as well as the straight lines of deco and expressionism, which I believe were directly taken from the traditional geometrical Greek patterns.

Circe is mysterious and beautiful, so I chose a vintage 20’s beaded shawl, to go with a 20’s inspired silver dress, to enchant and allure. The black eye makeup highlighted with gold is homage to both the sun god Helios, and the contrasting colours of art deco.

The 20’s were also a period of burgeoning sexual self-expression which I thought were perfect for the independent and seductive Circe, who utilizes her power as a form of self-protection against the men who invade her island constantly, turning them into animals, as represented by my (admittedly grumpy) cat! It also was in the 20’s that black cats began to be associated widely with witchcraft, through films and magazines, as did the spread of the popularity of tarot cards, which I also have here. Overall, I wanted to create an impression of Circe’s power and mystery through the self-staged and styled photos.

James Wilson

"A Father and Son Story" is “The Odyssey” as viewed and portrayed by a 6-year old Telemachus.

Xander Spencer-Jones at King Edwards School, Bath

"A Father and Son Story" is “The Odyssey” as viewed and portrayed by a 6-year old Telemachus.

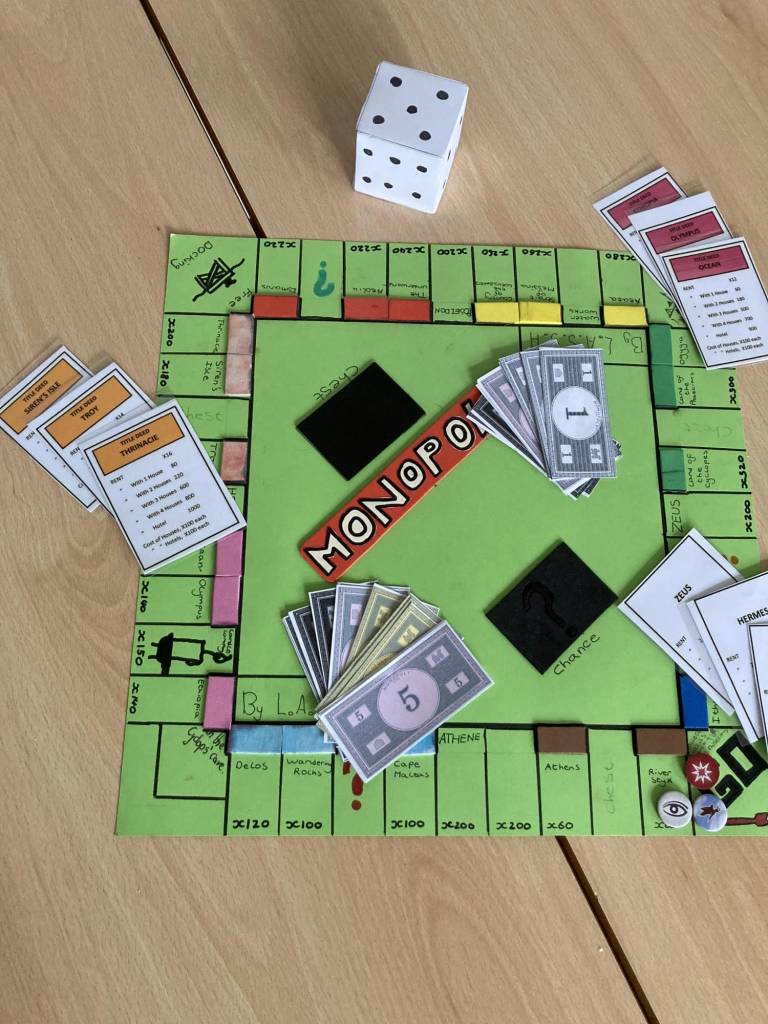

Stephen Janssens at King Rochester

A particularly talented group of pupils (Hugh, Alex, Seb and Lewis, our director of the Odyssey Festival!) at King’s Rochester produced the Odyssey edition of Monopoly.

Chenqing AN at UCL

"The Wine-dark Sea": I took this photo near the lake Mendota (The lake is so big and beautiful that people might think her as a “sea” on the first glance) at the campus of UW-Madison (United States), during a sunset on April 15th, 2019 when I was studying at the Department of Classics and Near Eastern studies at UW-Madison as an international visiting student from China during my senior year.

It was my first time to set foot and live for such a long period on a foreign land with the aim of studying Classics (definitely a lot of Homer and thus the Odyssey), and just a month ago Prof. Emily Wilson came to Madison gave an amazing lecture on her experience of translating the Odyssey. Thus, I couldn’t understand the Odysseusean nostalgia no more. While, this wine-dark “sea” was some breathtakingly beautiful that she healed all the wounds inflicted by my missing home and the family. Also, an unofficial but poetic Chinese translation, mostly using by the international students who speaks Chinese, of Lake Mendota is “梦到她湖” (pronounce as Mèng Dào Tá) which literally means “Dreaming of Her” in Chinese. Needless to say, Odysseus would definitely weep for his Penelope, if he learned such beautiful meaning.

On the other hand, my photo might also offer a new way of rethinking the discussion of Homer's semantical inability to distinguish between the color of wine and the one of the sea, which, as the photos shows, sometimes can appear in the same color and thus supports Rutherfurd’s (1983) description. [Rutherfurd-Dyer, R. "Homer's Wine-Dark Sea." Greece & Rome 30, no. 2 (1983): 125-28.]

Maddy Penelope

Bori Papp

Written

- Emily Keen at Strode College, Somerset

I am an English & Creative Writing Fda undergrad at Strode College, Somerset and received an assignment last year to write a piece inspired by a classical text. After we studied The Odyssey in class, I was drawn to Odysseus as my inspiration because of his deceitful nature and confusing relationship with home.

Click on text above to download full poem

Commentary

Inspired by Emily Wilson’s translation of The Odyssey (Homer and Wilson, 2018), my piece began as a response to the significant preoccupation with home. While researching Wilson’s interpretation, Odysseus’ motivations on his epic journey homebound became particularly fascinating. “We have these models by which Odysseus is constantly insisting that by holding out in disguise or in absence…he can eventually become the exact the same person he always was.” (Jordan Alexander Hill, 2018)

I turned my attention to Odysseus’ conflicted relationship to home as presented in this translation. His journey takes 20 years by sea, and he returns to his homeland of Ithaca roughly midway. Curiously, he does not reveal himself immediately. Only in the penultimate Book does he make himself known to his own wife. Encounter after encounter, Odysseus deceives his acquaintances, friends and family through lies, embellishments and most favourably, disguise.

Odysseus’ peculiar choices about returning home transform his character from one that is desperate to return, to someone who requires “the fantasy of permanent patriarchal dominance over a carefully regulated human household.” (Homer and Wilson, 2018, p. 61)

Narrowing the parameters, I selected Book 5 (Homer and Wilson, 2018, p. 180-196) and the catalytic actions of Zeus to develop Threshold. Odysseus is betrayed, and his clear path home threatened. Castaway on foreign land, he seeks refuge under a bush of reassuringly domestic olive and tyrannical trident like thorn, “…to save the seed of fire and keep a source” (Homer and Wilson, 2018, p. 196). Odysseus conceals himself in order to preserve himself. He becomes deceitful and borderline delusional in his view of the world and I wanted to extract and encapsulate this hidden undertone of his motivations in a characteristically distorted way. I pitched it in poetic form to echo that of The Odyssey (Homer and Wilson, 2018), with descriptive language such as ‘bright eyed’, ‘rosy fingered’ and ‘misty seas’ inspired by the translation. In terms of meter, it is not strictly either Dactylic Hexameter (original) or Iambic Pentameter (Wilson’s translation), but it reflects the intended emphasis of words, sometimes hitting a rhyme, sometimes not. Repetition is sympathetic to the translation and a move from polyvocal narrative to first person is intended to reinforce the notion of internal dialogue and self-preservation. The application of ‘Threshold’ not only echoes the physical lines Odysseus crosses on his journey, but additionally the metaphorical cusp of deceitfulness.

On reflection, by exploring Odysseus through this piece, I feel the strength of the story lies in his complicated character. Upon reading adaptions and interpretations, it has been interesting to explore the idea that although deceitful, Odysseus is accessible. He desires home, but not the passing of time and concealment or absence provides his escape.

Bibliography

Block, E. (1985). Clothing Makes the Man: A Pattern in the Odyssey. Transactions of the American Philological Association (1974), [online] 115, pp.1–11. Available at: https://www.jstor.org/stable/pdf/284185.pdf?refreqid=excelsior%3A6dfd1a4...9a1db536 [Accessed 9 Feb. 2020].

Homer and Wilson, E.R. (2018). The Odyssey. New York ; London: W.W. Norton & Company.

Jordan Alexander Hill (2018). Classicist Emily Wilson: Why Homer’s Odyssey is a Great Story -

The Western Canon Podcast. YouTube. Available at:https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kmDuHzFymoA [Accessed 14 Nov. 2020].

Kellaway, K. (2019). Nobody by Alice Oswald review – given up to the fateful waves. [online]

the Guardian. Available at: https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/oct/01/alice-oswaldnobody-review-... [Accessed 13 Dec. 2020].

podcasts.ox.ac.uk. (2020). Interview with Water | University of Oxford Podcasts - Audio and Video Lectures. [online] Available at: https://podcasts.ox.ac.uk/interview-water [Accessed 13 Dec. 2020].

Poet Seers. (n.d.). Poet Seers » “Odysseus.” [online] Available at: https://www.poetseers.org/contemporary-poets/w-s-merwin/merwin-poems/ody... [Accessed 13 Dec. 2020].

Poets, A. of A. (n.d.). We Were All Odysseus in Those Days by Amorak Huey - Poems | Academy of American Poets. [online] poets.org. Available at: https://poets.org/poem/we-were-allodysseus-those-days [Accessed 13 Dec. 2020].

Richardson, S. (2006). The Devious Narrator of the “Odyssey.” The Classical Journal, 101(4), pp.337–359.

www.bclt.org.uk. (n.d.). Sebald Lecture 2019 - BCLT. [online] Available at: http://www.bclt.org.uk/sebald-lecture-2019 [Accessed 14 Nov. 2020].

- Emma Lefevre at Strode College, Somerset.

Poem Calypso, inspired by The Odyssey.

Click the text above to download the full poem

Commentary

Emily Wilson’s translation of the epic poem The Odyssey (Wilson, 2018) is the inspiration for my interpretation of the Calypso and Odysseus relationship. I was intrigued by the idea of the unreliable narrator, and how all these epithets: ‘cunning’ Odysseus, ‘the great teller of tales’; ‘the

man of many resources’ and ‘the man of twists and turns’ point to a person whose narrative may not be entirely accurate. His ease with deception sheds doubt on his trustworthiness. This is not a novel interpretation. The roman satirist Juvenal wrote:

‘. . .When Ulysses

narrated this crime over dinner, he shocked King Alcinous

and some others present, perhaps, who, angry or laughing, thought him a braggart

liar.’ (Metzger, 2016) [1]

Indeed, Zeus in Wilson’s translation recognises Athena’s duplicitous actions: “Ah! Daughter! What a thing to say! Did you not plan all this yourself,” (Wilson, 2018 4.22-23). This highlights for me how the depiction of truth is linked to who is telling the story.

The narrative structure of this poem echoes that of the original form. I follow Wilson’s storytelling techniques quite closely, including where the narrative perspective is focused, shifting from Calypso, to Odysseus and to Mount Olympus. I chose to start with a structure like the original ‘Tell me about’ and ending with Odysseus’ departure. Other specific features include the use of epithets to identify the characters and in a nod to ‘rosy-fingered dawn’ I use ‘palms of dawn’. I have stuck closely to the original epithets for each character with the exception for Athena ‘the green-eyed goddess’ her common epithets include ‘grey-eyed goddess’ or ‘bright-eyed goddess’ and I change the colour to symbolise her jealousy. I also use a couple of extended metaphors; one on the beach representing a growing sexual awareness and the other to describe the harrowing experience of the nightmares with the aim of giving more visual imagery to understand the concept.

I attempt to give each voice an identity and language, using shorter tentative sentences from Calypso to underline her vulnerability as she recalls her story. In an attempt to underline the intensity of their union I switch from using first person singular to first person plural. Unlike the original poem, there is an unexpected twist at the end when I reveal the couple have had several children. Researching the character, I found three sons who are sometimes attributed to this union.[2] In the original the myths of the Greek heroes were already well known by the audience and there would be no surprises in the narrative.

Linguistically I want to use some of the key features of Wilson’s translation. I have attempted to use assonance and alliteration to create rhythm and sounds similar to the sea. I was keen to create a rhythm although there is no regular meter.

While I captured the original voice, structures and forms well at the beginning of the poem, this became more challenging as I attempted to convey a new and different narrative in a way that could be convincing. I also wanted to include some psychological insight into why the characters behave in the way that they do, I’m not sure how successfully I achieved this.

[1] Printed in Juvenal. The Sixteen Satires. Translated by Peter Green. Penguin Classics, 1998, p. 115.

[2] Hesiod, Theogony 1011 Hesiod, Theogony 1019, Sir James George Frazer in his notes to Apollodorus, E.7.24, says that these verses "are probably not by Hesiod but have been interpolated by a later poet of the Roman era in order to provide the Latins with a distinguished Greek ancestry".

Bibliography

Hall, E., (2008). The Return of Ulysses; A Cultural History of Homer's Odyssey.

Hall, E., (2020). Edith Hall On the Homeric Tradition. [online] The British Library. Available at:<https://www.bl.uk/greek-manuscripts/videos/edith-hall-on-the-homeric-tra... [Accessed 27 October 2020].

En.wikipedia.org. (2020). Calypso (Mythology). [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Calypso_(mythology)> [Accessed 14 November 2020].

En.wikipedia.org. (2020). Epithets in Homer. [online] Available at: <https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Epithets_in_Homer> [Accessed 14 November 2020].

Metzger, D., (2016). Episode 13: His Mind Teeming. [online] Literatureandhistory.com. Available at: <https://literatureandhistory.com/index.php/episode-13-his-mind-teeming>[Accessed 14 November 2020].

Theodorakopoulos, E. and Cox, F., (2013). Responding to Homer: Women's Voices | Oupblog. [online] OUPblog. Available at: <https://blog.oup.com/2013/03/responding-to-homer-womensvoices/> [Accessed 22 October 2020].

Wilson, E., (2019). Sebald Lecture 2019 - BCLT. [online] Bclt.org.uk. Available at: <http://www.bclt.org.uk/sebald-lecture-2019> [Accessed 4 November 2020].

Wilson, E., (2018). The Odyssey Homer. London: WW Norton and Company

- Flynn Kendall at The John Lyon School

This is a short poem written by Flynn Kendall in response to the key themes and characters of the epic, which we have been exploring alongside Shelley’s great sonnet: Ozymandias.

Odyssey, a journey through Greece,

Death or life, kill or be killed,

Your favourite characters travelling through an unknown world,

Sirens, cyclops and many dangerous monsters,

Survival in Poseidon's merciless sea,

Everlasting Gods and mere mortals, wreaking revenge,

You, reading the epic poem of justice and fate.- Rhys Belsham at Bexley Grammar School, London

The poem details the journey that Odysseus made by sea, starting with his raid at Ismaros, and ending with his arrival at Ithaka.

- Monty Hunt at West London Free School Sixth Form

I wrote this poem, Dear Penelope, from the perspective of Odysseus himself; I imagined Odysseus writing a letter to his beloved wife Penelope, to inform her of the numerous adventures he has survived since the Fall of Troy up until the sirens – roughly summarising the story Odysseus tells King Alcinous throughout Book IX-XII of the Odyssey. I wrote the poem in a formulaic structure which is suddenly disrupted when Odysseus is overwhelmed by rapid memories of his danger-filled past – ultimately, Odysseus settles when he is reminded of his underlying source of hope – his sweet Penelope.

- Jonathan Huish at UCL

I studied and wrote a 5,000 word essay on C.P. Cavafy’s Modern Greek poem Second Odyssey last year for the KCL module ‘C.P. Cavafy: the making of a modernist’ with Professor David Ricks. It’s a poem I’ve been coming back to ever since. In many ways Second Odyssey is an early version of – or precursor to – one of Cavafy’s most famous poems, Ithaca. As one of his unpublished poems, it has attracted much less attention than Ithaca, though I would argue that it is a more interesting poem than it gets credit for. I think it is therefore worthy of inclusion in UCL’s ‘living archive’ of the Odyssey.

- Murray Boyle at King Edward VI School Southampton

The poem is on Odysseus’ journey home to Ithaca. At 4468 words, it’s the longest one I have written to date. I wanted to share it because it combined my 2 greatest loves of poetry and Ancient History and I hope you enjoy reading it.

- Emma Kurr at St Albans High School for Girls

The poem is something I wrote when Homeric poetry just wouldn’t leave me alone (I’m sure you know how it is), and the title may be so very grammatically incorrect but unfortunately all I had to hand was the lexicon at the back of my copy of John Taylor’s Greek to GCSE, so I hope you will forgive any inaccuracies. I didn’t want to call it “Odysseus, the man of twists and turns”, because as obnoxious as it must sound (I know it does), I don’t think the English does the epithet justice.

And honestly, the poem is essentially just a sporadic semantic field of Odyssey related things, but the Odyessy wasn’t in chronological order so neither am I.- Jim Kimber at Dubai College

This is a comedy radio play I wrote a few years ago, based on the Odyssey: I was successful in a BBC competition for new writers with the original draft (which was long...) and I was offered some work to write for the News Quiz etc. as a result, but that was the summer I moved to Dubai and I just couldn't take up that work. They told me they were very interested in this radio play but it would need some editing. I have since reworked the radio play to fit the Radio 4 15-minute drama format, but have not managed to get it produced. I know it has much potential and I would love to give it wider circulation - maybe some students might like to make an audio recording of it one day (I would love to hear it read by actors.) I would be really happy to engage with any students who would like to work on it, make some edits and make a recording.

- Toby Brothers at London Literary Salon

I was scheduled to take a group of 14 readers to Greece later this spring for a study of The Odyssey on the island of Agistri-- as that won't be happening, I am putting my energy into reflections on the Odyssey.

Reflections on Xenia in the Modern World

“Man of misery, whose land have I lit on now?

What are they here -violent, savage, lawless?

or friendly to strangers, god-fearing men?”

The Odyssey by Homer- VI, 131-133At the heart of the Homeric universe is Xenia (Greek ξενία, xenía): the Greek concept of hospitality, or generosity and courtesy shown to those who are far from home or unknown. It is often translated as "guest-friendship" (or "ritualized friendship") because the rituals of hospitality created and expressed a reciprocal relationship between guest and host. XENOS (the singular form) translates to: guest, host, foreigner, stranger and friend. For the ancients, stranger is a temporary state that with right protocol translates to friend.

Those that do not offer—or go so far as to desecrate- the rituals of hospitality show themselves to be ‘savage, lawless’—and are isolated, rejected and fought if they have invaded.

I am thinking about how in the ancient world as humans attempted to move from lives of violent struggle for survival to civilized existence, negotiating the encounter with strangers was vital. The way in which two people come to know each other, the movement from stranger to guest to friend, sits in core of our social system and is the early testament to our ascension into civilization—towards the best of human enterprise.

Although Republican members of the US government (along with other anti-immigration advocates in mostly western countries) may not understand this—their response to reject desperate migrants from ravaged places shows their collapse of civilized behavior in the face of fear. The Brexit travesty has its roots in a similar rejection of the stranger: the desire to draw an exclusive border that quickly reveals itself to be self-destructive in economic, cultural and political realms—and that is just three weeks in.

In recent years I have felt frozen with inaction in the face of the deaths as the result of acts of terrorism—and then appalled by the response, born of fear, to close borders and stoke frantic nationalism. I sat down to a wonderful group working their way through Proust’s epic and felt the absurdity of discussing social manipulations and aristocratic degeneracy while the world burns. Unlike a dear friend who is dedicating her work to migrants arriving in Greece, I sit here in North London and agonize and promote reading literature.

I do not think that however iron-clad we make our borders, however much we employ surveillance on ourselves or those we have defined as our enemies, we will ever eradicate terrorism until people everywhere have homes that are safe and food to eat and the freedom to live as they choose. This era of global pandemic highlights how tempting it is to draw an enclosing circle around ourselves and grab life-saving resources for those in our nation.

The Odyssey offers a variety of responses to the encounter with the stranger. Some of the kingdoms Odysseus encounters live in a way that models civilized, progressive human behavior over violent and random inhumanity: and that means welcoming people who arrive on your shores in need, negotiating with right protocol your encounter with a stranger, offering a meal before you ask someone to tell their story. We can probably skip the offer of a bath with the scented oil rubdown as the precursor to the sharing of food and drink—although maybe that would help.

I accept that refusing to treat every migrant as a terrorist may mean that I will suffer—that me or my family or someone in my community will be killed because desperate people are rejecting the claims of the civilized society. I also understand that safety is not a guaranteed right –because my safety usually comes at the expense of another’s: for me to be absolutely safe the enforcing powers would make some assumptions about who is good and who is evil (always those defined as outsiders) and reject those whose profile causes concern. It seems to me a kind of arrogance that suggests I deserve to be totally safe while Syrian children are sleeping in freezing forest as their desperate parents risk everything to scrape out a life away from immediate fear.

In Ancient Greece, communities would take the risk of welcoming a stranger into their midst not knowing if their hospitality would be reciprocated with gifts or blood. Taking that risk: offering humanity first outweighed the risk that the stranger would respond inhumanely. In parts of Greece today, that same generosity is still being enacted as refugees are brought to shore on the island of Rhodes, Lesbos and other shores.

Imagine that, from beginning of the Syrian civil war, the Western countries had responded by spending billions on aid instead of the billions spent on military response—on supporting Turkey, Lebanon, Greece and Jordan in welcoming the migrants –how would this have changed the perceptions of Syrians toward the West?

Coming out of ten years of fighting the Trojan War, Odysseus had to learn to approach strangers & unknown communities without the impulse to attack. Here I may find the start of action in the face of my helplessness: approach the stranger with humanity. Accept the risk that there are people who have learned inhuman responses—but I will not let their inhumanity instruct mine.

- Maili Jordan Hanna from Lossiemouth, Scotland

I have written a villanelle about Odysseus’ suffering and the consistent drive for home throughout his journey.

- Amanda Potter at the Open University, London

This is a magical fantasy adventure story based on the Odyssey featuring two teenage girls, the Bronze Age princess Nausikaa, and Em, a geeky schoolgirl from Brighton. Together they go on a journey round Europe to find out the truth about the monsters, about Odysseus, and about each other. Written in lockdown, the story allows us to travel with the heroines, even when we are not able to physically travel ourselves.

Link: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1dI5T6yPhIuZmKxXrl13js_9ULPFRI9CF/view?usp=sharing

Audio

Holly Rusling and Eleanor Bowen at Wakefield Girls' High School

We were inspired by the Sirens in the Odyssey and we wanted to create a song for them to entrance Odysseus but that was less sensualized than most pop-culture!

Rachell Stott

A piece I wrote in 2011 called 'Odysseus in Ogygia'. It is a 15 minute tone poem (piece of instrumental music illustrating a narrative) based on Book V of the Odyssey.

Close

Close