Staging Greek Tragedy: Then and Now

Browse our short series 'Staging Greek Tragedy: Then and Now' in occasion of UCL's 2022 Classical Play (Euripides' Electra, 9-11 February), featuring acclaimed artists and academics being interviewed by this year's production crew on matters concerning the staging of Greek tragedy in ancient and modern times

- Episode One: Dramaturgy and Greek Tragedy

Browse our short series 'Staging Greek Tragedy: Then and Now' in occasion of UCL's 2022 Classical Play (Euripides' Electra, 9-11 February), featuring acclaimed artists and academics being interviewed by this year's production crew on matters concerning the staging of Greek tragedy in ancient and modern times.

Special Guests: Dr Estelle Baudou (Marie Curie Research Fellow and Dramaturg) and Professor Oliver Taplin (Oxford)

Production and Organisation: Dr Giovanna Di Martino

Productions mentioned in the episode:

1981, Peter Hall, The Oresteia, NT, London

1978, Yukio Ninagawa, Medea, Tokyo.

1986, Antoine Vitez, Electre (Electra), Chaillot, Paris.

1988, Deborah Warner, Electra, RSC, The Pit, Barbican Centre, London.

1990-1992, Ariane Mnouchkine, Les Atrides (Iphigenia at Aulis and The Oresteia), Théâtre du Soleil, Vincennes.

1991, Katie Mitchell, Women of Troy, Gate Theatre, Notting Hill, London.

1996, Katie Mitchell, The Phoenician Women, RSC, Other Place, Stratford-upon-Avon.

1999-2000, Katie Mitchell, The Oresteia, NT, London.

2000, Deborah Warner, Medea, Abbey Theatre, Dublin.

2001, Katie Mitchell, Iphigenia at Aulis, Abbey Theatre, Dublin.

2007, Katie Mitchell, Women of Troy, NT, London.

Further Reading:

Billings, Joshua, Budelmann, Felix and Macintosh, Fiona (eds), 2013, Choruses, Ancient and Modern, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Cole, Emma, December 2015, ‘The Method behind the Madness: Katie Mitchell, Stanislavski, and the Classics’, Classical Receptions Journal, Volume 7, Issue 3, 400-421.

Cornford, Tom and Svich, Caridad, 2020, ‘Katie Mitchell’, Contemporary Theatre Review, Volume 30, Issue 2.

Foley, Helene, 2007, ‘The Tragic Chorus on the Modern Stage’, in Kraus, Chris, Goldhill, Simon, Foley, Helene and Elsner, Jas (eds), Visualizing the Tragic: Drama, Myth, and Ritual in Greek Art and Literature. Essays in Honour of Froma Zeitlin, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Revermann, Martin, 2021, Brecht and Greek Tragedy, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Stanislavski, Konstantin, 1980, An Actor Prepares, London: Eyre Methuen.

- Episode Two: Set, Props, and Costumes and Greek Tragedy

Special Guests: Dr Rosie Wyles (Kent) and Dr Michael Loy (Assistant Director of the British School at Athens)

Production and Organisation: Dr Giovanna Di Martino

Further Reading:

On the prehistoric settlement of the Argolid: French, E.B. 2002. Mycenae: Agamemnon's capital: the site in its setting.

Iakovidis, S.E. 1985. Mycenae - Epidaurus: Argos, Tiryns, Nauplion. A complete guide to the museums and archaeological sites of the Argolid.

Ley, G. (2007) A short Introduction to Ancient Greek Theater. Chicago

Kimberly Beaufils' PhD thesis (2000) Beyond the Argo-Polis. A social archaeology of the Argolid in the 6th and early 5th centuries BCE. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10121053/

Ley, G. 2009. 'A material world: costume, properties and scenic effects', in McDonald, M. and Walton, M. (eds), The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Theatre.

Rehm, R. (2020) Euripides Electra. London.

Taplin, O. (1978) Greek Tragedy in Action. London.Wyles, R. (2011) Costume in Greek Tragedy. London.

On the recent archaeological discovery at the theatre at Thouria mentioned in the episode: https://chronique.efa.gr/?kroute=report&id=6526

Productions mentioned:

Yukio Ninagawa, Medea, Nissei Theatre (Tokyo), 1978. Useful reading on the production: Smethurst, M. (2002). 'Ninagawa's Production of Euripides' Medea', American Journal of Philology 123, 1-34. Yannis Kakleas, Euripides' Orestes, Epidaurus (Athens Epidaurus Festival), 2021. Useful links: ttp://aefestival.gr/festival_events/orestes/?lang=en https://www.athensvoice.gr/culture/theater/722216_eidame-ton-oresti-toy-gianni-kaklea-stin-epidayrohttps://www.kathimerini.gr/culture/561439585/ekriktikos-orestis-dia-cheiros-kaklea/

- Episode Three: Translation, Adaptation, and Greek Tragedy

Special Guests: Dr Giovanna Di Martino (UCL) and Professor Fiona Macintosh (Oxford)

Production and Organisation: Dr Giovanna Di Martino

Further Reading:

Bigliazzi, Silvia, Kofler, Peter and Ambrosi, Paola (2013), ‘Introduction’, in Silvia Bigliazzi, Peter Kofler and Paola Ambrosi (eds), Theatre translation in performance, New York: Routledge: 1-26.

Carne-Ross, D. S. (1961), 'Translation and Transposition', in William Arrowsmith and Robert Shattuck (eds), The Craft & Contextof Translation, Austin: University of Texas Press: 3-21.

L. Hardwick (2007), ‘Translating Greek tragedy to the modern stage’, Theatre Journal 59 (3): 358-61.

Link, Franz H. (1980) ‘Translation, Adaptation and Interpretation of Drama Texts’, in O. Zuber (ed.), The Language of Theatre: Problems in the Translation and Transposition of Drama, Oxford.

Laera, Margherita (2014), ‘Introduction: Return, Rewrite, Repeat: The Theatricality of Adaptation’, in Margherita Laera (ed.), Theatre and adaptation: return, rewrite, repeat, London: Bloomsbury: 1-17.

Macintosh, Fiona (2013), ‘Theater Translation and Performance’, in: Georgios K. Giannakis (ed.), Encyclopedia of Ancient Greek Language and Linguistics, Brill.

- Episode Four: Music, Dance and Greek Tragedy

- Special Guests: Dr Marie-Louise Crawley (C-DaRE) and Alex Silverman (Music Composer and Director)

Production and Organisation: Dr Giovanna Di Martino

Further Reading:

Csapo, E. 1999. 'Later Euripidean music', Illinois Classical Studies, 24/25: 399-426.

D’Angour, A. 2018. 'Ancient Greek music: now we finally know what it sounded like', The Conversation <https://theconversation.com/ancient-greek-music-now-we-finally-know-what-it-sounded-like-99895>

Gianvittorio-Ungar, L. and Schlapbach, K. (2021) Choreonarratives: Dancing Stories in Greek and Roman Antiquity and Beyond, Leiden: Brill.

Klavan, S.A. 2021. Music in Ancient Greece: Melody, Rhythm and Life, London: Bloomsbury.

Leslie, S. (2010) 'Gesamtkunstwerk: Modern Moves and the Ancient Chorus' in F. Macintosh (ed.), The Ancient Dancer in the Modern World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 411-419.

Pöhlmann, E. 2020. Ancient music in antiquity and beyond, Berlin: De Gruyter.

Weiss, N. 2018. The music of tragedy: performance and imagination in Euripidean theater, Oakland: University of California Press.

West, M.L. 1992. Ancient Greek Music, Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Willson, S. and Eastman, H. (2010), 'Red Ladies: Who are they and What do they Want?', in Macintosh, F. (ed.) The Ancient Dancer in the Modern World, Oxford: Oxford University Press, 420-430.

Zarifi, Y. (2007) 'Chorus and dance in the ancient world', in M. McDonald and J. Michael Walton (eds.), The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Theatre, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 227-46.

Videos and Essays on Euripides' Electra

What Euripides’ audience saw and what he wanted them to see (Dr Michael Loy)

- The Reception of Euripides' Electra in Michael Cacoyannis' work (Dr Anastasia Bakogianni, Massey University, New Zealand)

- Euripides’ Electra: an introduction (Dr Antony Makrinos)

- Electra was the daughter of Agamemnon and Clytemnestra and sister of Orestes and Iphigeneia. Although she plays an important role in Greek tragedy, she is not mentioned in epic. Euripides’ Electra was produced sometime before 415 BC. and although it was generally received with less enthusiasm than Medea or Hippolytus, it is now widely accepted as a work of intense tragic energy. The plot of the play relates to the story of Electra and Orestes which has been dramatized by the three great tragedians, Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides. It is the story of the two children of Agamemnon who seek revenge for the murder of their father after his victorious return from the Trojan War and at the hand of his wife Clytemnestra. Electra and Orestes conspire to kill their mother and their uncle Aegisthus who is her lover and the usurper of Agamemnon’s throne.The play starts with a farmer who introduces us to the story of the siege of Troy and Agamemnon’s murder by Aegisthus and Clytemnestra and informs us about the current state of the two protagonists: Orestes is in exile after having escaped death from the hands of Aegisthus and Electra has been married to the humble farmer and cast out of her house. However, Agamemnon will not stay for too long without revenge. Orestes has come back together with his friend Pylades to take revenge; he has given his father’s tomb an offering of tears and hair and looks for his sister as an active participant in the future murder of their mother.Already from the beginning of the play, we are introduced to Electra’s horrible state and we are invited to feel pity for our heroine: the princess and daughter of the victor of the Trojan War is dirty, devoid of her royal status, miserable, unloved, isolated, and she does not participate in public life. She spends her nights lamenting for the unjust death of her beloved father and blames the gods for not interfering in Agamemnon’s murder:None of the gods listen to the voice of the unhappy one, none to my father’s blood shed long ago.(Eur. Electra 198-200, trnsl. J. Morwood)The only light of hope in her grief is Orestes, her liberator. The first contact of the two siblings is full of irony. Electra does not want him to touch her because she does not know his identity and Orestes pretends to have news from her brother who is alive. The introduction to the recognition scene between the two siblings might not be as emotionally powerful as that in Sophocles’ Electra but nevertheless is incredibly important for our heroine. It emphasises the antithesis of the joyful news of Orestes being alive and the misery of Electra’s emotional world which is currently full of lamentation and grief. This is a tragedy about brotherly love and how it can serve justice. Electra adores Orestes, misses him and longs for his return. She wants to have him back to plot the murder of their mother and Aegisthus. However, Orestes asks Electra a lot of information to enrich his knowledge about her life and the situation in Mycenae. The information communicated by Electra serves to further emphasise the audience’s sympathy to the princess who has now fallen to a state of a common woman who works for her clothes and water and who has lost her royal status. Whilst Clytemnestra and Aegisthus enjoy power and wealth, everything that relates to Agamemnon has been neglected and abandoned: his tomb, his son, his daughter.The recognition scene is carefully constructed and follows similar scenes in the Odyssey. Similarly to the way in which the old servant Eurykleia recognised the beggar Odysseus from the scar on his knee when he came back to Ithaca, the old man recognises Orestes from a scar on his eyebrow. The sign persuades Electra (initially hesitant and with disbelief similarly to Penelope in Odyssey 23) that this is her brother. The stichomythia between the two siblings with the mutual exchange of half lines increases the emotional peak of the scene and fills the audience’s heart with satisfaction for the anticipated recognition:Orestes: And you are held by me at last.Electra: I never thought it would happen.Orestes: I too never expected it.Electra: Are you he?Orestes: Yes, your only friend...(Eur. Electra 578-582, trnsl. J. Morwood)In the first book of the Odyssey Athena advises Telemachus to look for his father and then to consider how he can kill the suitors who are in his household and dishonour him and his father. Athena argues that Telemachus is no longer a child and that he should follow Orestes’ example:Or have you not heard what glory was won by great Orestes among all mankind, when he killed the murderer of his father, the treacherous Aegisthus, who had slain his famous father?(Hom. Odyssey 1.298-300, trnsl. J. Lattimore)Athena refers to Orestes as a hero who fulfils the heroic ideal and takes revenge on the unlawful killing of his father by his murderer; she brings him as an example of a boy who has become a man and took the responsibility of his actions (what Telemachus has not yet done at the beginning of the epic). It is this kind of mature Orestes that we see here, a hero who first tries to understand the situation in his city, explores the grounds for friends and attempts to plan the time and method of his revenge and its success.But Orestes is not as alone as Telemachus. He has the old man who saved him to advise him, and Electra who in this play is a very active agent and wants to help her brother. When he asks about whether to kill them both at the same time, Electra delivers a chilling line that breaks the stichomythia between the Old Man and Orestes:I shall arrange the killing of my mother(Eur. Electra 647, trnsl. J. Morwood)Even their prayers to the gods for the success of their task are well planned. They carefully choose their divine allies: Zeus, the father of the gods with the supreme power (from whom Agamemnon’s power and leadership was given in the Trojan War); Hera, his wife and the protectress of family, marriage (which Clytemnestra has destroyed) and the city of Argos; and finally, Queen Earth who encloses the body of the dead Agamemnon and who can release his ghost. In a society in which justice is served by revenge, there is no space for failure: Electra tells Orestes she will commit suicide, if he fails: her life is now in his hands.The audience of Electra must not forget that the bloodline of Thyestes and Atreus, fathers of Aegisthus and Agamemnon, is cursed; the Chorus remis us of this a bit before the murders that will follow. Orestes keeps his promise, and he successfully kills Aegisthus, but the audience feels that this was the easy part of the siblings’ task. Aegisthus has killed Agamemnon to steal his throne unlawfully and he deserved his punishment. There is even a sense of justice being served and of satisfaction with Electra’s apostrophe to Aegisthus’ dead corpse and the delivery of a soliloquy about what she has suffered until now.But things do not seem to be so easy with Clytemnestra’s murder. Does she deserve to die? The dramatic tension of the play is built on the duplicity of answer to this question. Yes and no. Clytemnestra had reasons for killing her husband: first he sacrificed her daughter, Iphigeneia, at Aulis for the sake of a war in the name of Helen; second, he brought back from Troy to his marriage bed the daughter of king Priam, Cassandra as his second wife. Clytemnestra has only imitated the actions of her husband when she went with Aegisthus. Her arguments seem to be logical and powerful.However, Electra deconstructs the superficially logical arguments of her mother: Clytemnestra was looking to replace Agamemnon before Iphigeneia’s death which she used as a pretext for her husband’s murder. And if the reason for Clytemnestra’s killing of Agamemnon was Iphigeneia’s death, why did she not give Orestes and Electra their father’s house? Why did she drive them away? Why does she not bring Orestes back and obstruct Aegisthus from abusing Electra? Clytemnestra does not seem to have convincing answers to Electra’s questions and although she says she suffers for what she has plotted, this is not enough to save herself.At the end of the play Orestes and Electra kill their mother and they suffer the consequences of their actions. Electra’s lust for revenge has been transformed into remorse. Every prospect of a “happy ending” to their misery is cancelled by the absurdity of their actions: it was just that Clytemnestra died because she was a murderess, but matricide was equally a dreadful act for which the siblings will have to suffer separation and Orestes will have to face the Furies. The only salvation for Orestes will be to stand trial in Athens as it is revealed in the end of the play.

- What Euripides’ audience saw and what he wanted them to see (Dr Michael Loy)

It’s spring, late fifth century B.C., and you are on the south slopes of the Acropolis with the Parthenon behind you and the roofs of ancient Athens out in front. You are sat outside on curved wooden benches watching a troupe of masked all-male performers move across a circular dance floor, as you drink in a performance that boasts no curtains, no lights (the performance takes place during the day) and no amplification. You are watching the debut of Euripides’ Electra as it was first performed in the last decades of the fifth century B.C., part of a dramatic contest between three writers of tragedies, each presenting three plays, part of the religious festival of the Great Dionysia.

How do we know that this is what that world looked like? We could do worse than to look to the archaeological record, a body of evidence that allows us to see the material world that the original audience might have seen: objects, monuments and places that make the ancient texts more tangible. In this blogpost, we will look briefly at a few pieces of evidence that help us to imagine what that first performance might have looked like for Euripides’ audience in Athens —and we will also see some evidence for another world of ancient Greece to which the playwright wanted to transport us.

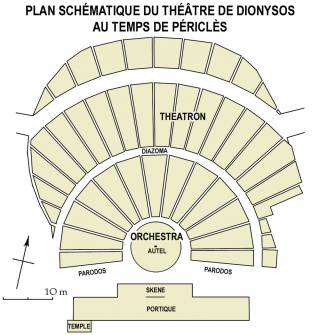

Ancient theatre spaces

The Theatre of Dionysos Eleuthereos is a monument that tourists of Athens can visit today. It sits built in to the slopes of the Acropolis hill, using the natural topography to form a tiered seating area that draws the audience’s view towards a central staging area. Today a rather grand theatre with three tiers of stone seating (the theatron area) and a raised platform built at the back of the stage, the monument that visitors see was largely constructed around 350 B.C., enlarged and further monumentalised in the Roman period (and restored and conserved in various sections in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries). The theatre design would have been much simpler in Euripides’ time, however. The tragedy’s action would would have played out on a circular orchestra space, while the seating area for the audience comprised wooden benches, ikria, the scaffolding posts from which slotted into postholes that have been found on the south-slopes. Behind the orchestra, it is likely that a permanent stone stage building, the skene, was erected some time around the second half of the fifth century B.C. —so perhaps in place by the time that Electra was performed. This building had stone foundations, plastered brick walls, and it could be dressed with scenery to enrich the audience’s view and to help transport their minds elsewhere.

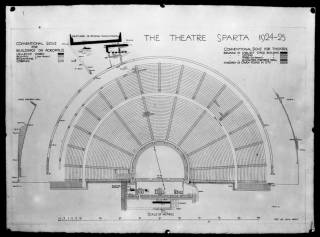

Recent archaeological discoveries are helping to enrich our understanding of ancient theatres. In 2016, Xeni Arapogianni of the Athens Archaeological Society began excavating an ancient theatre at the site of Thouria in Messenia. This structure dates a little after Euripides’ time to the fourth or third century B.C., but its construction is useful nonetheless for telling us more about how dramatic texts might have been performed in antiquity. Initial excavation concentrated on exposing the diameter of the orchestra (and investigating a two-storey workshop that had been built right in its centre, a reuse of space once the theatre had fallen out of use!), but at the end of the 2017 excavation period a clue came to light about how performances could have been staged here. Namely, stone channels were found just in front of the skene along which painted scenery pieces could have been rolled in and out: one can almost imagine the chorus of a play like Euripides’ Electra waltzing in and pulling in or out of view a decorated backdrop, helping the audience to ‘see’ a new place or image. The innovation of the stone channels is shared by the neighbouring theatre at Messene, and also east across the Taygetos mountain range at Sparta.

‘Real’ places in Euripides’ Electra

So much for the theatres that the Euripides' audience would have sat in —where did he want to take them?

The action of Electra takes place in the Argolid region of Greece, an area in the north-east area of the Peloponnese, just across the Saronic Gulf and west from Athens. This is a fairly dry and arid region of Greece —Homer calls it ‘very thirsty’— and it is only through a complex mechanical irrigation system that the region today has become a modest producer of citrus fruits, tomatoes and corn. The wide plain of Argos (in the middle of which the modern city lies, the same location as the ancient city) rolled out to the sea at the Argolic Gulf, and it was itself enclosed by hills on all sides.

Little is known archaeologically about Classical Argos, about the city that would have stood contemporary with Euripides’ play. The École Française d’Athènes has conducted excavations but, with a modern city right on top of the ancient, only small fragments have come to light, principally monuments from Roman period Argos. A medieval castle on the city’s hill of Larisa and a circuit of walls are thought to have been placed on top of classical monuments, and there would also have been rather grand gates leading into the city. What we know more about, however, (and perhaps more useful for thinking about Euripides’ text which asks his audience to look back to a ‘heroic’ past of Greece) is prehistoric Argos. On top of the Aspis hill, remains have been located of a fortified hilltop settlement. And just across the plain, too, more Bronze Age fortified settlements at Mycenae and Tiryns, ‘palaces’ enclosed by fantastic ‘Cyclopean’ walls whose defences would have been almost impossible to breach. Is this the sort of picture that Euripides wants us to have in our minds when he tells us about the palace that Clytemnestra inhabits, the doors of which are closed and unreachable, keeping Electra far away in the harsh and arid plain?

One reference to place in particular would have had special significance to Euripides’ audience in Athens. When the Dioskouroi enter the stage during its final moments deus ex machina, they instruct Orestes to go to Athens, to embrace the statue of Pallas Athena, and to stand trial at the Hill of Ares in order to cleanse himself of the bloodshed of his mother. The Hill of Ares, the Areopagos, stood a mere stone’s throw away from the Theatre of Dionysos, also on the slopes of the Acropolis and round to the west, boasting a proud view out across the Pnyx and the Agora, the heart of classical Athens and its legal processes. The Areopagos, although little more than just a meeting point for a council of high-ranking officials to take a decision in serious cases of murder and homicide, also had at its feet a small temple of the Erinyes (Furies), goddesses of vengeance and retribution. In some senses, by bringing Orestes to Athens at the end of the play right up-close to the audience, he was empowering that audience to be the jurors to this character, inviting them to start a conversation with one another: were Orestes’ actions in killing his mother just, and does he deserve for the council of the Areopagos to acquit him?

So not just challenges but possibilities are given by the use of space and real places in Euripides’ text. Euripides would have known well the space in which his words would be performed, and whether or not he wanted to use this opportunity to take his audience to other real or imagined places was all part of his stagecraft. That same challenge of negotiating imagined space and real place exists for any creative team staging a place like this, and I look forward to seeing how the 2022 UCL Greek Play team engage with that possibility

Study questions

1. What are the challenges for staging an ancient production of Greek tragedy posed by the physical layout of an ancient theatre?

2. Euripides’ Electra is set in Argos, but many other places are mentioned in the text (Troy, Mycenae, Phokis, Euboea). How important is it that an ancient or modern audience knows what these places look like, and where they are?

3. Could a production of Electra be staged in an entirely fictional ‘non-place’? What would be lost or gained?

4. Think about other plays of Euripides’ that you have read. Does the poet use space and place in the same way as he does in the Electra?

5. To what extent do you think Euripides’ Argos was inspired by the world of prehistoric Greece?

Further reading

Iakovidis, S.E. 1985. Mycenae - Epidaurus : Argos, Tiryns, Nauplion. A complete guide to the museums and archaeological sites of the Argolid.

Kimberly Beaufils' PhD thesis (2000) ‘Beyond the Argo-Polis. A social archaeology of the Argolid in the 6th and early 5th centuries BCE.’ https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10121053/

Ley, G. 2009. ‘A material world: costume, properties and scenic effects’, in McDonald, M. and Walton, M. (eds), The Cambridge Companion to Greek and Roman Theatre.

Papathanassopoulos, T. 1995. The sanctuary and theatre of Dionysos : monuments on the south slope of the Acropolis.

Spathari, E. 2010. Corinthia - Argolida: Corinth, Mycenae, Epidavros, Nemea, Argos, Tiryns, Navplio. A Guide to the museums and archaeological sites.

The theatre at Thouria is published in Greek, but English language summary reports for each of the excavation seasons 2016–2020 are available here:

https://chronique.efa.gr/?kroute=report&id=6525

https://chronique.efa.gr/?kroute=report&id=6526

https://chronique.efa.gr/?kroute=report&id=6893

https://chronique.efa.gr/?kroute=report&id=8563

https://chronique.efa.gr/?kroute=report&id=15910

The Ancient Greek Theatre - Parts and Machinery (3D)

Figures for What Euripides’ audience saw and what he wanted them to see

Fig. 1: Map of places mentioned in this blogpost. (produced by Michael Loy)  | Fig. 2: The Theatre of Dionysos as it stands today, looking from the west side. (Athen Akropolis (18512008726), dronepicr, CC BY 2.0, <https://www.flickr.com/photos/132646954@N02/18512008726/> via Wikimedia Commons) |

3. Schematic diagram of the Theatre of Dionysos (late fifth century B.C.), with different parts of the theatre named in Greek. (Theatre dionysos, Vol de unite, CC BY-SA 3.0, Wikimedia Commons <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Theatre_dionysos.gif>) | 4. Aerial view of the fourth/third century B.C. theatre at Thouria, taken after the completion of the 2019 excavation season. (Archaeological Society of Athens, Ergon (2019), 25-29)  |

5. Stone-built theatre at Messene. (Ancient Messene theatre 2, Dimap1981, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Ancient_Messene_theatre_2.jpg>)  | 6. Sparta: General plan of the theatre with cavea restored, 1925. (Glass negative, quarter plate, from BSA SPHS Image Collection, BSA SPHS 01/7473.C2595)  |

7. View across the Argolid region, from Mycenae. (View from Mycenae, Annatasch, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:View_from_Mycenae.jpg>)  | 8. View towards modern-day Argos from Larisa castle, where supposedly there would have been a classical Acropolis. (View towards Argos from Larisa castle (Acropolis of Argos, Argos castle, 2017), Gregor Hagedorn, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:View_towards_Argos_from_Larisa_castle_(Acropolis_of_Argos,_Argos_castle,_2017).jpg>  |

9. The Cyclopean walls of Mycenae. (George E. Koronaios, CC0 1.0, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Cyclopean_walls_of_Mycenae_o...)  | 10. A view of the Areopagos hill from the Athenian Acropolis. (George E. Koronaios, CC BY-SA 4.0, Wikimedia Commons, <https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:The_Areopagus_and_the_Hill_of_th...)  |

Close

Close