Tiny diamonds with unusual symmetry

Nanodiamonds are infinitesimally small crystals, about 10 to 20,000 times smaller than human hair. Because of their importance, they are the focus of several disciplines. They can be found in meteorites, in the vicinity of young stars (HD 97048, Elias), in interstellar dust (comets), and have been described from certain sedimentary layers that can be linked to asteroid impact, so their appearance is being studied by earth and planetary scientists. Nanodiamonds are also at the heart of materials science research. Due to their unique physical and mechanical properties, they are suitable for the production of hard and resistant coatings, abrasive powders and motor oil additives, as well as polymer and metal composites with exceptional properties. They are candidate nanomaterials as drug carriers and can therefore be used in medical treatments, especially in cancer medicine.

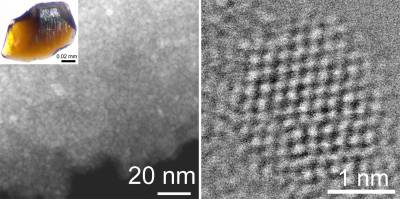

Despite their importance, understanding the internal structure of nanodiamonds has continued to pose a research challenge. Although it is widely accepted that their structure generally corresponds to that of diamonds, with a three-dimensional arrangement of covalently bonded carbon atoms, features of their electron microscopic, diffraction and spectroscopic characteristics differ significantly from those of the well-known diamond. According to the latest research results [1] of the international scientists from the Research Centre for Astronomy and Earth Sciences (Hungary), University College London (UK), University of Bath (UK), Arizona State University (USA), University of Cambridge (UK) and ESRF - The European Synchrotron (France), a significant fraction of the nanodiamond particles is not diamond, but corresponds to nanosized diaphite structures that consists of crystallographically intergrown diamond and graphite units that are bonded together. This new family of diamond-related materials has already been identified by the research team in their previous research conducted on asteroid impact and artificial shock-wave produced samples [2, 3]. This time, the researchers examined nanodiamonds from Orgueil and Murchison meteorites (Fig. 1) and an artificial sample produced by chemical vapor deposition using state-of-the-art electron microscopy and microbeam Raman spectroscopy and synchrotron X-ray diffraction [1]. The results were modeled using ab initio computational calculation techniques.

Fig. 1. Nanodiamond aggregates and an individual nanosize diamond from Orgueil meteorite.

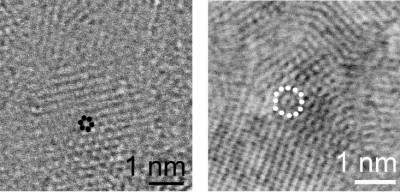

The scientists identified nanosized carbon particles with six- and twelve-fold crystallographic symmetries (Fig. 2), which cannot be explained in terms of the structure of normal diamond. The authors associated the appearance of the unusual symmetry with the presence of diaphite units. Structural modeling showed that the six- and twelve-fold symmetry appears only in certain projections of the grains but remains hidden in most of the possible crystal orientations relative to the viewing direction, so that recognizing the diaphite structure represents a serious challenge. This finding may explain why the existence of the nanosized diaphite domains may have been overlooked in previous research.

Fig. 2. Nanosize diaphite with 6 and 12-fold symmetries.

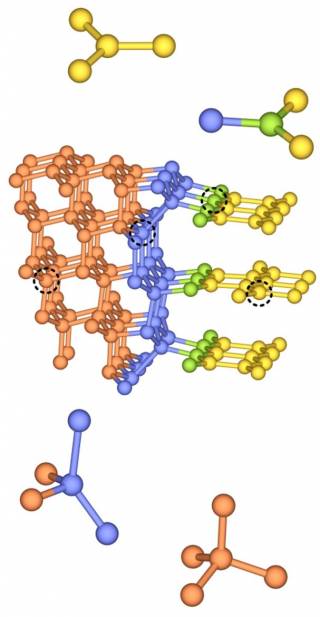

The research team determined the spectroscopic properties of diaphites using energy calculations and found that they match well with the experimental results for nanodiamonds. The authors concluded that the unusual features observed in nanodiamonds that are incompatible with those of normal diamond can be perfectly associated with differently bonded carbon atoms of the diaphite structure (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Carbon atoms with different bonding states in diaphites.

The study not only provides a convincing explanation for the contradictory microscopic and spectroscopic observations to date, but it also sheds light on the application possibilities inherent in the diaphite structure. The researchers point out that diaphites have excellent mechanical and electrical properties due to the carbon atoms occurring in different bonding states. By controlling the experimental synthesis conditions or using lasers to write features within specific areas of diamond layers would provide an excellent opportunity to consciously produce diaphite structures with specifically designed characteristics, thereby developing nanomaterials with tunable electrical properties that can be candidates for the semiconductor industry.

Citations

[1] Németh P, McColl K, Garvie LAJ, Salzmann CG, Pickard J, Corà F, Smith RL, Mohamed M, Howard CA, McMillan PF Diaphite-structured nanodiamonds with with six- and twelve-fold symmetries. Diamond and Related Materials 2021, 119,108573.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.diamond.2021.108573

[2] Németh P, McColl K, Garvie LAJ, Salzmann CG, Murri M, McMillan PF Complex nanostructures in diamond. Nat. Mater., 2020, 19, 1126-1131

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41563-020-0759-8

[3] Németh P, McColl K, Murri M, Smith RL, Garvie LAJ, Alvaro M, Pécz B, Jones AP, Corà F, Salzmann CG, McMillan PF Diamond-graphene nanocomposite structures. Nano Letts., 2020, 20(5), 3611–3619.

https://pubs.acs.org/doi/10.1021/acs.nanolett.0c00556

Close

Close