Towards better diagnosis of peripheral nerve tumours

28 October 2020

Research led by UCL highlights how advances in molecular pathology have improved the classification of rare cancers and provides new insights into tumours of the peripheral nervous system.

The study, published in the Journal of Pathology, shows that malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNSTs) can be classified into two major groups based on different genetic and epigenetic profiles. The findings provide a first step in improving diagnosis and developing a more personalised approach in the clinical management of patients with this disease.

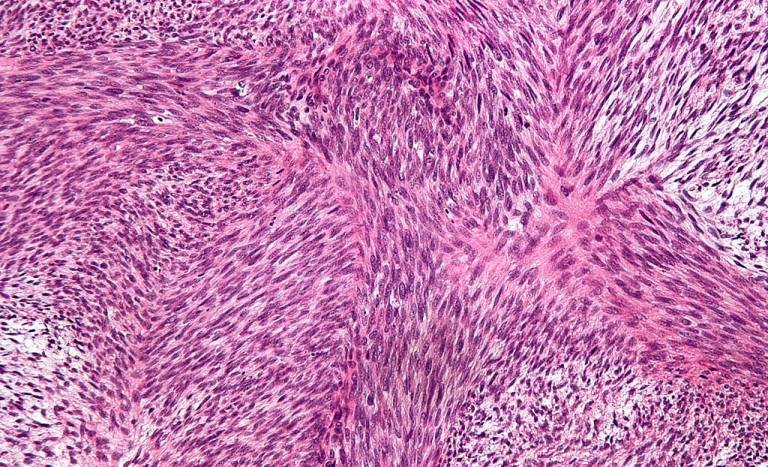

Diagnosis is central to patient care, suggesting which treatments are most appropriate and enabling clinicians to give patients some idea of their likely prognosis. Cancer diagnosis has traditionally relied on pathology, microscopic examination of tumour biopsies, but this is increasingly being supplemented with information from genetic characterisation of tumours.

Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours (MPNSTs) are relatively rare, accounting for around 5% of sarcomas. Almost half occur in individuals who have inherited a mutation in the NF1 neurofibromatosis gene, which increases the risk of a range of cancers, and 10% are associated with radiation exposure. MPNSTs are aggressive – fewer than half of patients survive for 5 years.

Diagnosis of MPNSTs by pathology is highly challenging. There are hopes that molecular analyses may provide greater clarity. In particular, mutations in EED and SUZ12, two genes involved in modification of histones, the proteins that DNA winds around, have been found in multiple MPNSTs. These could have a significant impact on control of gene expression, driving uncontrolled cell divisions. However, their contribution to MPNSTs remains uncertain.

Genetic and epigenetic profiles

To provide greater clarity, Iben Lyskjaer and colleagues from the UCL and the Royal National Orthopaedic Hospital (RNOH), the Medical University of Innsbruck and the Netherlands Cancer Institute analysed 176 cases where a diagnosis of MPNST had been considered. The team searched for mutations affecting EED and SUZ12, as well as for changes in patterns of histone methylation. The team also carried out a systematic pathological examination of the samples.

The combination of analyses has provided a much clearer framework for classifying MPNSTs. The results suggest that loss of EED/SUZ12-driven methylation is seen in 38% of MPNSTs overall, but in 76% of ‘classical’ histologically defined tumours. Notably, the presence or absence of EED/SUZ12-driven methylation distinguishes two distinct groups of tumour, and raises questions about what factors are driving malignancy in tumours retaining this methylation mark.

The findings will enable clinicians to gain a better understanding of an individual patient’s tumour, based on pathology, genetics and methylation analysis. Equally importantly, the study will now enable further research to be carried out to better understand the links between genetic abnormalities, alterations in histone methylation, histology and clinical features of disease in this poorly understood and hard-to-treat class of cancers.

International MPNST consortium

“Our work has helped to resolve discrepant findings on the proportion of MPNSTs showing loss of methylationH3K27me3. We are now contributing to an international Genomics of MPNST Consortium, which aims to identify the ‘drivers’ of cancer in MPNSTs where methylation is unaffected,” said Dr Iben Lyskjaer, Research Fellow (UCL Cancer Institute) and lead author of the study.

To accelerate progress, a global consortium – the Genomics of MPNST (GeM) Consortium – has been established to coordinate efforts to characterise MPNSTs. Funded by the NF Research Initiative and led from Boston Children’s Hospital, USA, the GeM Consortium comprises 10 sites, including the UCL Cancer Institute; its Steering Committee includes the UCL Cancer Institute’s Professor Adrienne Flanagan. The Consortium has collected nearly 100 MPNST samples, which will be systematically analysed using histopathological, genomic and multiple ‘omics’ technologies to identify associations between cellular changes and the clinical features of disease. The end result will be the largest data set ever generated for MPNSTs, which promises to reveal more about how these tumours develop and suggest therapeutic strategies to combat them.

“Through the GeM Consortium, we are coordinating effortsworking closely with a team of experts to understand these rare but deadly tumours, enabling us to make much more rapid progress. Ultimately, this will benefit patients, particularly families affected by neurofibromatosis.” said Professor Adrienne Flanagan OBE, Head of Pathology, UCL Cancer Institute and Consultant Histopathologist, RNOH.

This project has been supported by Sarcoma UK, Rosetrees and Stoneygate Trust, Skeletal Cancer Trust, and an RNOH NHS research and development grant. With additional support from the Carlsberg Foundation, Cancer Research UK and the NIHR UCLH Biomedical Research Centre.

Further information

- Research paper: H3K27me3 expression and methylation status in histologicalvariants of malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumours. Journal of Pathology

- Dr Iben Lyskjaer academic profile

- Interview with Dr Iben Lyskjaer - Bone Cancer Research Trust

- Prof Adrienne Flanagan academic profile

- Genetics and Cell Biology of Sarcoma - Flanagan Lab

- Genomics of MPNST (GeM) Consortium

- Research paper: Genomics of MPNST (GeM) Consortium: Rationale and Study Design for Multi-Omic Characterization of NF1-Associated and Sporadic MPNSTs. Genes

- Main image: Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumour. Wikimedia Commons

Close

Close