Do ‘microglia’ hold the key to stop Alzheimer’s disease?

8 May 2019

A Leuven research team led by UCL Queen Square Institute of Neurology Professor Bart De Strooper, UK DRI Director, studied how specialised brain cells called microglia respond to the accumulation of toxic proteins in the brain, a feature typical of Alzheimer’s disease.

The three major disease risk factors for Alzheimer’s—age, sex and genetics—all affect microglia response, raising the possibility that drugs that modulate this response could be useful for treatment.

One of the hallmarks of Alzheimer’s disease is the presence of so-called amyloid plaques in the brain. Research suggests that these plaques trigger a series of processes in which microglia play a central role. Microglia are specialised brain cells that act as the first and main form of immune defence in the brain.

“The response of these important support cells to the accumulation of toxic amyloid beta may have a big effect on the disease process. That’s why we wanted to understand better the microglial response to amyloid beta and how it may differ across individuals,” said Professor De Strooper.

“We know microglia get involved in Alzheimer’s disease by switching into an activated mode,” explained Dr Carlo Sala Frigerio, UK DRI Fellow, adding, “We were interested to know if ageing in the presence or absence of amyloid beta deposition would affect this activation.” Dr Sala Frigerio worked in De Strooper’s lab in Leuven and recently started his own group at the UK Dementia Research Institute at UCL.

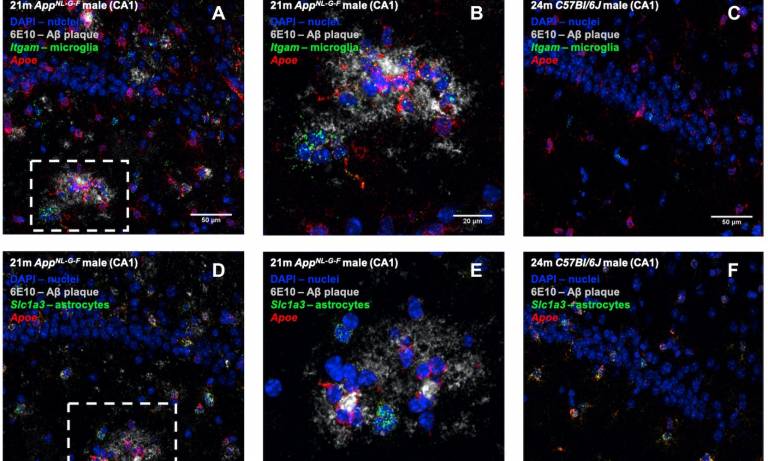

The researchers used a genetic mouse model in which amyloid beta progressively accumulates, mimicking the disease process in human patients. The team analysed the gene expression profiles of more than 10,000 individual microglia cells isolated from different brain regions of both male and female mice at different disease stages.

“We found that the microglial responses to amyloid beta were complex but could essentially be catalogued into two major activation states. The same two activation states that are found during normal ageing, but then activation was slower and less pronounced,” said Dr Sala Frigerio, UK DRI Fellow at UCL.

In female mice, the microglia reacted earlier to amyloid beta, especially if the mice were older. Similar findings resulted from analysing the microglia in a different Alzheimer mouse model and in human brain tissue.

“Our data indicate that major Alzheimer risk factors, such as age, sex and genetic risk, affect the complex microglia response to amyloid plaques in the brain,” said De Strooper. “In other words, different Alzheimer’s risk factors converge on the activation response of microglia.”

Both De Strooper and Sala Frigerio believe that the response of individual microglia will largely depend on their direct environment within the brain. They explained: “A particular challenge will be to dissect the distribution of microglia in different activation states across the brain. Such a detailed dissection could lead to a whole set of new drug targets that could be useful to tune the microglia response in a beneficial way.”

Close

Close