Climate change and mental health

26 July 2021

At a glance

- Climate change threatens mental health.

- Substantial evidence shows that high temperatures and severe weather events are linked to mental health issues.

- Eco-anxiety (worry about the environment) can cause psychological distress.

- The mental health implications of climate change have been historically neglected both in research and policy.

- Removing stigma around mental health is important to create resilient responses to mental health impacts of climate change and collect necessary data.

- The cost implications of climate change impacts on mental health need to be considered.

- Actions to mitigate climate change can positively influence mental health.

- Worldwide tracking of the mental health impacts of climate change is necessary.

- Key stakeholders such as policy makers, health care professionals, researchers and communities need to be brought together to share expertise, identify promising interventions and coordinate action.

What is the problem?

Climate change threatens mental health

Climate change has been recognized as a health emergency – but predominantly as a physical health emergency. For example, the Lancet Countdown that tracks health implications of climate change had until last year no explicit indicators for mental health consequences of climate change. The last climate conference (COP25) did not give great prominence to mental health and climate change, either in the main sessions or the side events. Whilst COP26 has chosen health as a priority area for science, the corresponding program does not mention mental health.

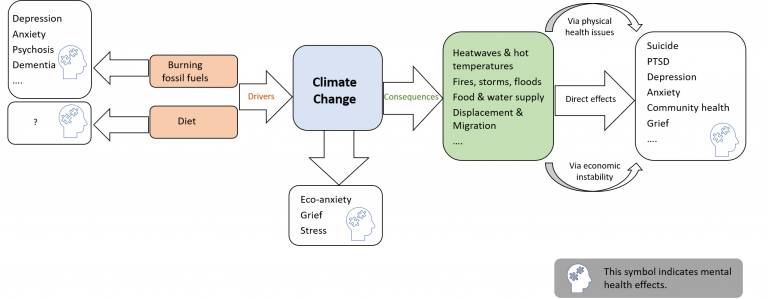

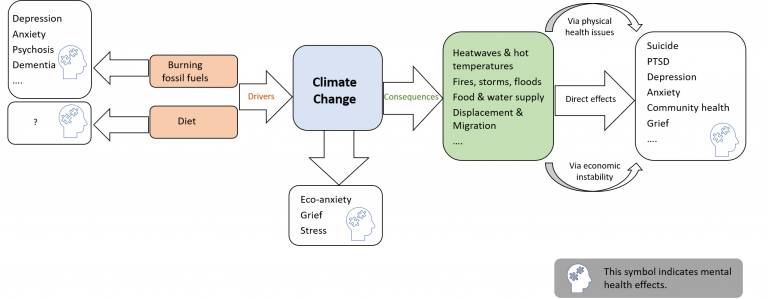

Mental health disorders are diagnosable illnesses such as depression and anxiety disorders. However, according to the World Health Organization (WHO) mental health is more than the absence of mental disorders. To be in good mental health means being able to realize one’s abilities, to cope with the normal stresses of life, to experience a state of well-being in which an individual realizes his or her own abilities, to work productively and be able to make a contribution to their community. Both the drivers and consequences of climate change can lead to mental health disorders and threaten emotional wellbeing; here referred to together as ‘mental health’.

The Lancet Global Health states that poor mental health was estimated to cost the world economy approximately $2.5 trillion per year in poor health and reduced productivity in 2010, with a projected rise to $6 trillion by 2030 (The Lancet Global Health, 2020). In England, the wider economic costs of mental illness are approximately £100 billion per year (HM Government, 2012). Worsening mental health due to climate change will bring huge additional costs; on the other hand, some of the solutions to mitigating climate change can also improve mental health.

What are the key characteristics of the problem?

Overall, evidence is limited on the relationship between climate change and mental health; but it is sufficient to indicate that climate change can negatively impact on mental health.

Some of the strongest evidence exists on a link between high temperatures and negative mental health effects. High temperatures and heatwaves have been linked to an increased rate of suicide. Hot temperatures have repeatedly been linked to an increase in violent crime – which may in turn negatively impact mental health. High temperatures can also lead to poorer sleep quality and reduced ability to work, leading to economic losses, which in turn can negatively impact mental health.

The experience of extreme weather events such as flooding or storms has been linked to an increased prevalence of depression, post-traumatic stress disorder and other anxiety disorders. This has been observed internationally and within the UK. Extreme weather events can also have negative economic consequences, for example if someone’s business is destroyed, which in turn threatens mental health.

Other consequences of climate change such as displacement and migration and insufficient access to food and water can both directly and indirectly affect mental health. They also threaten community health and wellbeing.

In principle, any consequence of climate change that can bring physical ill health can also have mental health implications, given that the two are closely linked, through various mechanisms, such as job loss, inability to afford health care, or a feeling of loss of control.

Eco-anxiety, defined by the American Psychological Association as “a chronic fear of environmental doom”, is particularly experienced by younger generations. It is not recognized as a disorder and in fact, could be seen as an entirely appropriate reaction to the fact that we are experiencing a climate emergency. Indeed, when linked to increased activism, it can have positive impacts on mental health; however, it can also trigger or worsen stress and mental health disorders.

Also, some of the causes of climate change have other effects that have been linked to mental health. Poor air quality resulting from the burning of fossil fuels can have negative mental health outcomes. Traffic noise can also be a mental health stressor and fossil-fuel powered vehicles are noisier than electric vehicles and active transport such as walking or cycling.

Burning fossil fuels for energy use in buildings, e.g. for air-conditioning, can contribute to warmer temperatures via the urban heat island effect which impacts on mental health. Certain diets – such as those high in ultra-processed food and high in meat – have negative environmental impacts and they might also have negative implications for mental health, but this area needs more research.

Figure 1. Simplified diagram of how drivers and consequences of climate change impact mental health.

Figure 1. Simplified diagram of how drivers and consequences of climate change impact mental health.

It is well recognized that climate change increases existing inequalities: The most marginalized people are at greater risk of experiencing climate change impacts, threatening their mental and physical health to a greater extent, and those already in poor mental health are more likely to be further affected. Also, the provision of mental health care itself, and access to it, is threatened by climate change. For example, a severe storm can destroy vital infrastructure, and subsequent displacement or forced migration can disrupt access to health care, if e.g. moving to an area where a different language is spoken.

What is the solution?

Tackling climate change, i.e. removing the root cause of the negative mental health impacts, needs to be the ultimate solution. Although most governments have policies in place to help tackle climate change, these policies will not result in the rate of reduction of greenhouse gases required. In part this is due because governments consistently underestimate the severity of the impacts of climate change and the benefits of mitigation. Mental health is a key area where the impacts have not even been quantified because it has been largely missing from the national and international policy agenda. Progress in this area will require tracking impacts of climate change on mental health; collecting appropriate data; employing metrics to calculate the mental health costs related to climate change and creating high-profile networks and events to champion this topic.

Given the comparatively weak evidence on the mental health impacts of climate change, it will also be necessary to conduct new interdisciplinary, high quality, applied research to answer open questions in this area.

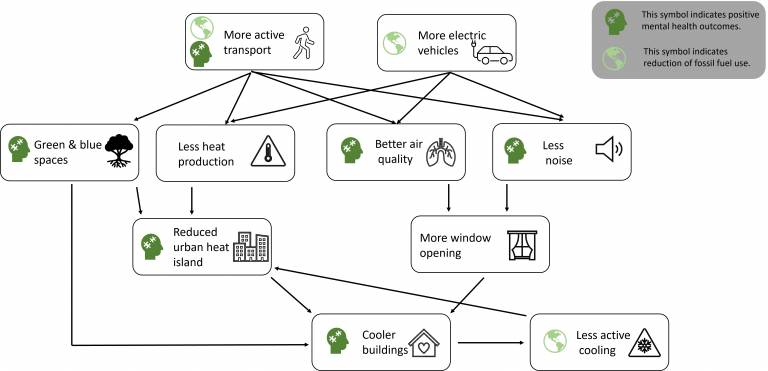

Ultimately, climate change adaptation and mitigation solutions need to be chosen that maximize other benefits (see Figure 2) and avoid negative consequences for mental health. Also, appropriate funding and resources need to be provided to prevent and treat mental health issues linked to climate change. Even with the most ambitious policies, further climatic change is now inevitable given the longevity of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere – hence, a consideration of mental health issues is essential.

What is stopping the solution being implemented?

The implications of climate change on physical health have been recognized – however, we do not know enough about the magnitude and cost of these mental health effects.

Part of the problem is lack of data. Measuring the prevalence of mental health disorders – even not considering climate change – is difficult and often only estimates are available that are likely underreporting true prevalence. Many countries don’t have the necessary infrastructure for mental health data collection, and collecting these data linked to climate change is even harder. In various countries around the world, mental health is still stigmatized. For example, fewer than 100 countries collect high quality data on suicide.

How can these barriers be removed?

Focus on other benefits of mitigating climate change

Actions that mitigate climate change can at the same time benefit mental health, creating a win-win situation, often with multiple routes to mental health ‘co-benefits’.

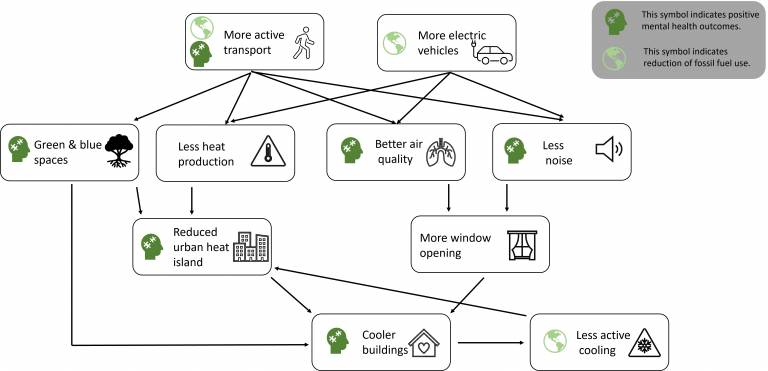

Figure 2 shows an example: Reducing fossil-fuel powered traffic through a move to electric vehicles and through more active transport such as walking and cycling directly reduces greenhouse gas emissions. At the same it can improve mental health. Being active is beneficial for mental health as are lower air pollution levels. Electric vehicles and active transport create less noise – beneficial for mental health - and they also produce less heat, mitigating the urban heat island effect. Less air pollution and lower noise levels can allow building occupants to open windows more, helping to cool buildings down and reducing negative health implications through too warm internal temperatures. Infrastructure for active transport can reduce the surface area of roads and parking spaces; allowing creation of green and blue spaces which are in themselves beneficial for mental health. Whilst billions of trees would need to be planted to have any meaningful impact on carbon dioxide concentrations, green and blue spaces can have a more immediate local effect, such as reducing the urban heat island effect and providing a passive system for solar control of buildings, i.e. contributing to cooler buildings. Cooler buildings reduce the need for active cooling through air-conditioning which in turn contributes to reducing the urban heat island effect further.

Figure 2. Co-benefits of reducing fossil-fuelled transport.

Figure 2. Co-benefits of reducing fossil-fuelled transport.

In general, providing better buildings, i.e. buildings that are possible to cool and heat adequately – and affordably, will benefit mental health. Costing in these benefits for mental health can make climate change mitigation effort more cost-effective and also help to address social inequalities.

And, of course, measures to mitigate climate change should not themselves have unintended consequences for mental health; e.g. creating new infrastructure for renewable energy can disrupt or even displace individuals and communities.

The need for research

Whilst sufficient evidence exists to call for consideration of the mental health effects of climate change, it is insufficient to allow clear quantification of the mental health costs and benefits related to climate change and its mitigation. Given that this topic is very much multidisciplinary, e.g. includes social, medical and environmental science, interdisciplinary research is needed. Key stakeholders need to be included, such as policy makers, health care professionals and communities which are particularly susceptible to mental health issues related to climate change.

Proactive measures to prepare quick responses and build resilience

Extreme weather evens often demand a fast response that in the first instance might focus more on physical aspects around a disaster. Planning an emergency response before an event actually happens allows planning for longer-term support. Having a robust health care system in place that values the public benefits of good mental health is essential. This will allow more appropriate emergency responses but also help create a society in better mental health to start with that might be more resilient to climate change related impacts.

Reduce stigma around mental health

Stigma reduction programmes can reduce stigma around mental health. However, these programmes need to be carefully planned, implemented and evaluated to ensure they can be a success. Providing consistent and sufficient funding for such interventions is crucial. Less stigma around mental health will facilitate collecting the necessary data but also building a better health care system with a focus on mental health.

Conclusion

The impact of climate change on mental health is an overlooked, but crucial topic. Sufficient evidence exists to suggest that both the drivers and consequences of climate change can worsen mental health and exacerbate existing inequalities. In particular, hot temperatures have been linked to increased suicides, and extreme weather events to post-traumatic stress disorder. The costs of the effects of climate change on mental health need to be considered in climate change policies. Actions to mitigate climate change can have substantial co-benefits for mental health and are therefore more beneficial than sometimes assumed. More evidence needs to be generated to allow more accurate estimations of the costs and benefits related to the mental health impacts of climate change. Removing the stigma around mental health is crucial to ensure accurate data can be collected and the necessary mental health infrastructure put into place. Creating a global network could help to bring this crucial topic of mental health and climate change to the forefront of climate change policies.

Key references for further information

- Clayton, S., Manning, C., Krygsman, K., & Speiser, M. (2017). Mental health and our changing climate: Impacts, implications, and guidance. (PDF)

- Lawrance, E., Thompson, R., Fontana, G., & Jennings, N. (2021). The impact of climate change on mental health and emotional wellbeing: current evidence and implications for policy and practice. (PDF)

- UCL Minds Podcast - Climate Change and Health: Exploring Co-benefits of Climate Actions

References cited in the text:

- HM Government. (2012). No Health Without Mental Health: A cross-government mental health outcomes strategy for people of all ages.

- The Lancet Global Health. (2020). Mental health matters. In The Lancet Global Health (Vol. 8, Issue 11, p. e1352). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2214-109X(20)30432-0

Close

Close