Biden and Harris’ first 100 days of climate action

28 April 2021

At a glance

- People all over the world should welcome the renewed engagement of the US administration with climate action.

- The target to halve emissions by 2030 is bold, but achievable.

- The challenge may be more social and political than technological – Biden and Harris must bring the country with them.

- If they succeed, this could prove to be a historic moment in the history of climate action.

What is the problem?

America is back – but there’s a long road ahead

As President Joe Biden and Vice President Kamala Harris reach 100 days in office, people all over the world should welcome the renewed engagement of the US administration with climate action. Within hours of his inauguration, President Biden brought the US back into the UN Paris Agreement on Climate Change, and a week later signed a further Executive Order, ‘putting the climate crisis at the center of United States foreign policy and national security’. The appointment of John Kerry as Special Presidential Envoy for Climate was another significant signal of intent. And last week President Biden hosted a climate summit of 40 world leaders, announcing that America would target an emissions reduction of 50-52% below 2005 levels by 2030. As a White House statement declared, using a now familiar slogan – ‘America is Back.’

This is a remarkable turnaround from the US being out in the cold on climate, to having one of the most ambitious national targets of any country. But while President Biden and Vice President Harris will garner praise internationally for this, the domestic politics could be more challenging.

What are the key characteristics of the problem?

What does the USA’s new target cover?

The target covers all greenhouse gases. Carbon dioxide (CO2), mainly produced from the burning of fossil fuels, accounts for about 80% of the country’s greenhouse gas emissions. However, other greenhouse gases also contribute, including methane, nitrous oxide and fluorinated gases, from agriculture, industry, chemicals and related products. The target is intended to cover all of these.

Is the target strong enough?

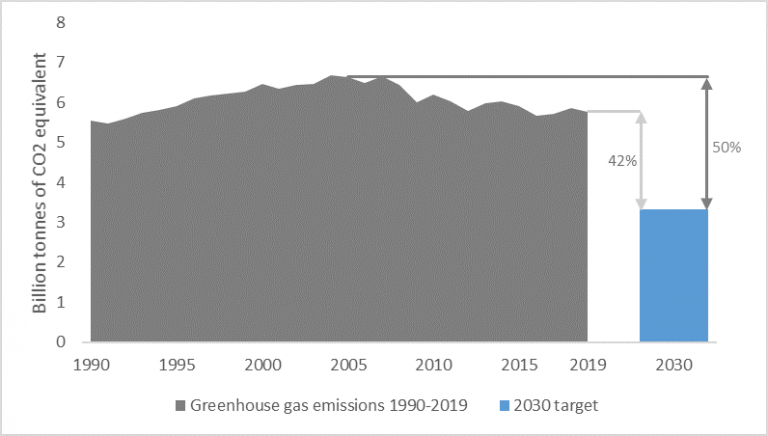

In order to have a chance of limiting global warming to 1.5°C, the world as a whole needs to cut emissions in half by 2030, and continue on a similar trajectory thereafter, reaching net-zero emissions by around the middle of the century. On the face of it, the US target for a halving of emissions by 2030 would seem to be perfectly in line with this global plan. However, to be precise, the US target is for a 50-52% reduction in emissions from the 2005 level. As shown in the graph below, emissions have already fallen since then, which means that when expressed as a percentage reduction from current levels, the targeted reduction is a little less than 50%. Using the most recently available data, a 50-52% cut from 2005 levels would be around a 42-45% cut from 2019 levels. So the pace of reduction is in fact slightly behind what is required at the global level to stay below 1.5°C.

Figure 1 US greenhouse gas emissions – a 50% reduction from the 2005 level is a 42% reduction from the 2019 level. Historic net greenhouse gas emissions data from US Environmental Protection Agency

Furthermore, many would argue that a simple translation of the global emissions reduction to equivalent country-level percentage targets is too simplistic, and that justice and fairness demands that some countries take the lead with more ambitious targets. The USA is a high-income country, with the largest greenhouse gas emissions per person, and the largest historic responsibility for emissions. From these facts, it could be argued that mirroring or being slightly behind the global average trajectory is not enough for the US – that it should rather set targets that are substantially more ambitious than the global average requirements.

But nonetheless, this is evidently a step-change from the position of the previous administration, and without a doubt moves the US back into the ‘big league’ – where it belongs – of countries making pledges that convey the requisite seriousness about addressing climate change.

What does the target mean for the USA?

In a series of executive actions, Biden has announced initiatives to support the transition – but what will this transition look and feel like to Americans?

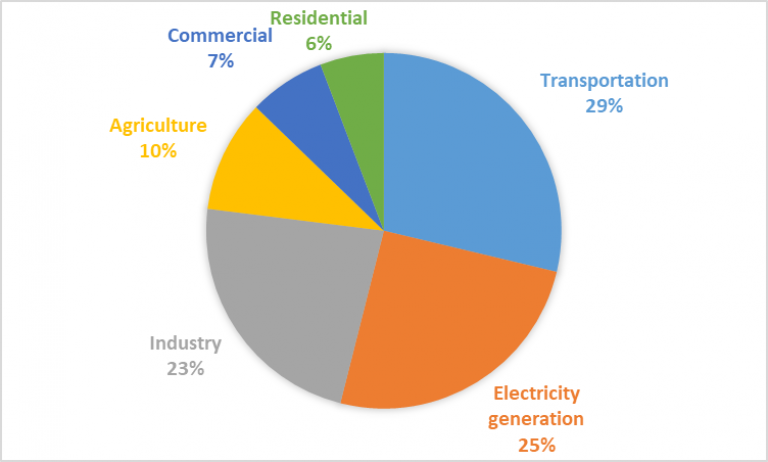

The graph below shows America’s greenhouse gas emissions by economic sector in 2019, thereby giving an impression of what kind of contribution different sectors could make to the overall cut by 2030.

Figure 2 US greenhouse gas emissions by economic sector in 2019. Data from US Environmental Protection Agency

Experience in other countries shows that the range of available low carbon electricity generation technologies, including renewables and nuclear power, means that this sector often leads the way in decarbonisation. Other sectors such as transport, industry and the heating of buildings, are usually harder to decarbonise and can take longer. On the basis of the current shares of emissions shown in the graph above, the complete decarbonisation of US electricity would remove around 25% of emissions. The US has introduced a goal to reach zero emissions from electricity by 2035. This implies that electricity generation emissions would be substantially cut, but not quite zero, by 2030. In order to reach a 45% cut in 2030, large reductions would then also have to be achieved in some of the other sectors. This could involve the conversion of more technologies to use the low-carbon electricity that would then be available – for example an increased use of electric vehicles for transport, or the electrification of industrial processes such as steel production.

In summary, the 2030 target could imply a near total transformation of the electricity sector, as well as very substantial changes in technologies in at least two other major sectors.

What is the solution?

A modest Moon shot?

In purely technological terms, the challenge is certainly achievable. When President Kennedy announced to a joint session of Congress in 1961 the ambition of reaching the Moon within the decade, the technological advances needed to meet that goal were substantially greater than those needed from the present moment to meet Biden’s 2030 goal. The costs of low carbon technologies such as wind power and solar PV have fallen dramatically within the last few years. Electric vehicles are getting closer to achieving a range per charge comparable to the range a conventional vehicle achieves on a full tank, and the total costs of owning an electric vehicle are increasingly competitive. In these and other sectors, a range of potential technological solutions exists.

In 1961 President Kennedy announced to Congress the goal of reaching the Moon within the decade. Image Credit: NASA

What is stopping the solution being implemented?

It’s not just technology

But achieving sufficiently broad social and political support may be a greater challenge than making the technology work. The 2030 target requires a substantial and rapid transformation of the US economy. In order to achieve this, citizens, investors and companies will need clear, consistent and long term policy signals that give a clear framework to make sense of and reward the low-carbon-consistent actions that they take.

Presidential executive actions may not be sufficient. Legislation will be required that gives the targets purchase, and brings about the actions required to meet the targets. Enacting these requires bringing the diverse American people along with the programme, and getting sufficient support in Congress, while still delivering something that is sufficiently transformative to meet the task. With millions of Americans working in fossil fuel industries, and Congress finely balanced between Democrats and Republicans, Biden and Harris will require all of their political skill to succeed.

How can these barriers be removed?

A just transition

Biden’s success will depend largely on his ability to implement the principles of a ‘just transition’ within his own country, ensuring that communities currently dependent on fossil fuel industries are supported and enabled to thrive in a transformed economy.

Biden is keenly aware of this, and eager to stress optimistically the job creation potential of the zero-carbon transition. However, it is not a certainty that all of the new green jobs created will be American ones. Whilst US companies like GE, First Solar and Tesla are major players in the manufacturing of wind turbines, solar PV modules and electric vehicles respectively, they also have major global competitors, including in Asia and Europe.

Biglow Canyon Wind Farm, Oregon. Image Credit: Portland General Electric on Flickr

Even if US-based green jobs are created, it is not a certainty that they will directly re-employ those losing work from fossil fuel intensive industries, which could lead to regional disparities within the country in the costs and benefits of the transition.

Market support policies that give companies clear and long term signals to plan for innovation and deployment are crucial, and have been shown to have substantial impacts in driving down costs of new technologies. However, for countries interested in capturing the wider employment and supply chain benefits of the transition, investment in research, development and pre-market demonstration is crucial to build up domestic supply chains and give the best possible chance of domestic job creation. Re-training is also crucial to transfer as far as possible the skills of those currently employed in fossil fuel industries to the new green sectors. But it is also important to acknowledge that in some cases a simple job-for-job transition will not be so easy. (We will explore the jobs issue further later in our COP26 Campaign). In such cases, other kinds of transitional arrangements, including direct investments into communities that stand to be decimated by the decline of carbon-intensive industries, may be justified.

In order to help make these more place-specific connections, leadership at many levels will be needed. Nowhere has this been more clear than in the US, when during periods of federal retrenchment from global climate politics, the activities of the states continued to progress the climate and sustainability agendas. The states will continue to have a crucial role, and the harmonisation of state and federal policies within the framework of the commitments set out in Biden’s plan, will be critical to future progress.

Finally, anxieties about strong climate commitments have historically been framed in internal US politics in terms of giving away the country’s competitiveness to international rivals. However, by being an international leader, the US has the potential to make a substantial contribution to the international momentum which may in time help to change the picture on international competitiveness – to create a race to the top, rather than a race to the bottom. But this will be highly dependent on consistency.

In a working democracy, a divided public can foreshadow an inconsistent country-level response to difficult global challenges. This has been played out in the contrasting approaches of recent US Presidents to climate politics. Obama played a crucial role in the Copenhagen Accord, and joined the Paris Agreement; Trump left and Biden re-entered. To international observers, the impression may be, for now at least, one of inconsistency, and to wonder whether any targets set now could simply be reversed by a future resident of the White House. In contrast, if President Biden and Vice President Harris are able to institutionalise a consistent climate commitment within US politics, this could be a legacy of profound global significance.

Conclusion

The first 100 days in office of President Biden and Vice President Harris have been eventful in many ways, not least among which has been the dramatic re-engagement of the US with the global climate process. If the administration can build on these steps to bring together a sufficiently broad constituency of domestic support for the required measures, thereby establishing a more consistent presence for the US within the international climate arena, it could also turn out to be one of the more significant ‘100 days’ in the long history of global climate action.

We will return to discuss these and other issues later in this programme, especially as part of our ‘international’ theme in September. But for now, happy first 100 days to President Biden and Vice President Harris – and welcome back America!

Key references for further information

The US Environmental Protection Agency provides information on US Greenhouse Gas emissions, from which the graphs in this explainer were drawn.

You can read about the Biden-Harris Administration’s approach to climate action here.

Close

Close