In 1973, Bartlett student Nick Wates’ 3rd-year report started a campaign to prevent a speculative office development from destroying an inner London neighbourhood. It’s still talked about today.

Group photo of squatters in Tolmers Square, organised as part of the campaign against eviction, 1975. Credit: 'Tolmers in Colour: Memories of a London Squatter Community' by Nick Wates with Mae Dewsbery and Caroline Lwin.

“Britain’s cities are in chaos. While thousands of houses stand empty there are not enough homes for people to live in. While acres of land lie derelict, many thousands of building workers are unemployed. Transport is congested and inadequate, and unemployment in the city centres is higher than the national average. Yet whole areas are still being destroyed to make way for office developments, which frequently have little social value, and merely exacerbate the problems.

This is Nick Wates writing in the introduction to his 1976 book, The Battle for Tolmers Square. The book would record two decades of events that took place in one small corner of central London, events that “both demonstrate the forces that operate in city redevelopment, and show how different forms of opposition can be more or less effective”.

Three years earlier, Nick Wates had been in his final year of an undergraduate course in Architecture, Planning, Building and Environmental Studies at The Bartlett, then known as the School of Environmental Studies. There were rumours that the Georgian terraced housing and small businesses right across the road from the The Bartlett were facing demolition and redevelopment for offices. Local people were worried. So Wates and four fellow students (Jill Baldry, Elizabeth Britton, Pedro George and Pete Henshaw) decided to collaborate on a project, under the tutorship of Mike Macrae, that would focus on this small 12-acre area of central London known as ‘Tolmers Square’.

“We investigated the truth about the development plans and undertook a survey of the area to find out who and what would be affected,” says Wates. “We invited some of the local people we had met to come into the college to discuss our findings before we finalised our report.”

Living / bathroom, 19 Tolmers Square, 1975. Credit: 'Tolmers in Colour: Memories of a London Squatter Community'.

Squatters marching from Tolmers to the High Court on the Strand to challenge a court order for eviction, 1975. Credit: 'Tolmers in Colour: Memories of a London Squatter Community'.

Their ‘Tolmers Square – Third Year Planning Project’ report turned out to be a galvanising force. Some of the locals decided to set up a community organisation to represent their interests, founding the Tolmers Village Association. Thanks to a grant from the Rowntree Foundation, Wates was able to become the first coordinator of the Association and several students, including Wates, squatted empty houses in the square. Over the next two years, 49 houses were occupied by over 180 people.

Upping the ante

With Wates at the helm, the Association ramped up its communication programmes. The Tolmers News was started to keep people informed, with 26 Issues published over the next four years (all compiled and edited by different people) and there was a campaign report, Tolmers Destroyed, that set out what was going on in the area, its style strongly influenced by the then popular Counter Information Services reports.

Articles in national magazines followed, such as ‘The Tolmers Village Squatters’ in New Society, and students wrote essays and dissertations on the subject. Wates’ own contribution was ‘Can Planners be Radical?’, for The Bartlett’s Development Planning Unit.

Film-maker Philip Thompson, who happened to work in the area, decided to produce a documentary film about it all. Tolmers: Beginning or End? aired on BBC2’s Open Door slot twice during 1975. Sunday Observer film critic Clive James called it: “…a telling, angry ‘World in Action’ – type… programme (which) did credit to the concerned and imaginative involvement with common life, which is the best vestige of the now superannuated Youth Culture.” Two extracts from the film by Blackstone Edge Productions can be found on Youtube.

Declaration of the 'Tolmers Garden' on derelict land in Drummond Street, 1974. Credit: 'Tolmers in Colour: Memories of a London Squatter Community'.

Mural on a former bank building at the entrance of Tolmers Square, north side. Credit: 'Tolmers in Colour: Memories of a London Squatter Community'

Part of the fabric of the city

Bartlett School of Planning Teaching Fellow Michael Edwards was one of Wates’ tutors during the 1970s. An activist himself – he had been involved in opposing the Greater London Council’s Covent Garden Plan several years before – Edwards says The Bartlett and its students saw themselves as part of the fabric of the city.

“The Bartlett was an institution which was, in many ways, very permissive or facilitating. I don’t remember ever being ticked off or told to stop doing this activist work. I don’t remember being encouraged much either. But it seems to me that’s just how a university should be. It worked very well.”

Edwards says his own activism was “very much linked” with his research interests. “I’m really interested in the distribution of who gains and who loses from urban change. This whole question of trying to oppose major destructive capitalist ventures in the city was, in a way, part of my research, part of my activism, and part of my teaching.”

Leaving a legacy

By 1976, Wates felt it was time to tell the whole story about Tolmers Square, which had, in one form or another, been going on for two decades. He set everything down in what would become the book,The Battle for Tolmers Square. Designed by Katy Hepburn, who had previously worked with Monty Python, its goal was to use the events at Tolmers to illuminate important issues that were happening everywhere. That sentiment was echoed in the publishers publicity for the book’s launch, which declared: ‘We all live in Tolmers Square’. Fittingly, the book launch was held in a squatted house in Tolmers Square (No 6).

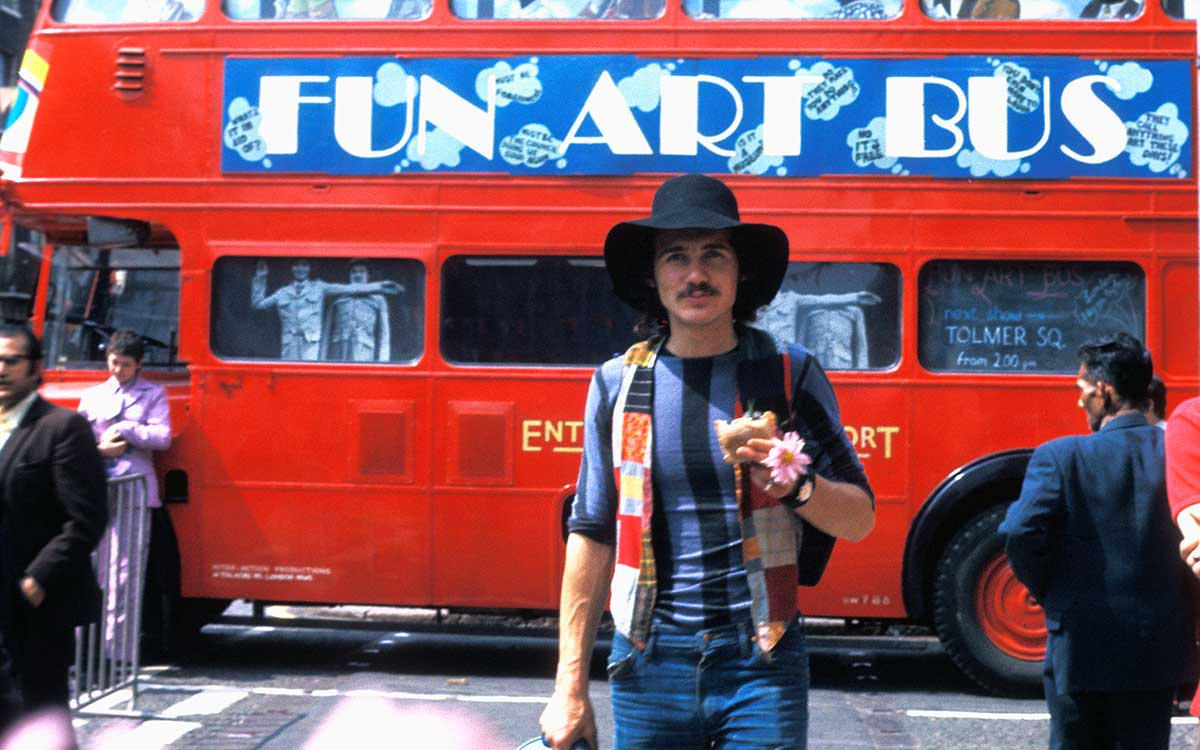

Bartlett alumnus Nick Wates, North Gower Street, 1974. Credit: 'Tolmers in Colour: Memories of a London Squatter Community'.

In a last ditch attempt to save the original square from development, a ‘Tolmers People’ plan had been produced. Though unsuccessful, the scheme that came to be built did include many elements that the Association had campaigned for, so much so that the local Council even celebrated the scheme’s completion with a special supplement in the local paper about it and an event in a local community centre.

“The impact of the book was to ensure that the Tolmers Square development was high profile during the final negotiations and completion of the development, and the eviction of the squatters,” says Wates.

The long-term impact has been to establish Tolmers Square as one of the most well-documented case studies of inner-city neighbourhood development and radical community politics of the 1970s. Academic initiatives have used it to test interactive computer modelling of development (led by Michael Batty at the University of Wales Institute of Science and Technology) and it was the subject of a detailed analysis of commercial property development by Jamie Gough at Middlesex Polytechnic – 20 Years of “Planning” the Tolmers Square Office Development, published in 1981.

More than three decades later, Tolmers Square is still being talked about. It featured in the 2010 exhibition and book, ‘Goodbye London; Radical Art and Politics in the Seventies’, by Peter Cross and Astrid Proll, and in 2013 Routledge decided to reissue The Battle for Tolmers Square in its Routledge Revivals series. And last year, The East End Preservation Society organised a conversation about the contemporary relevance of the experience.

Wates says: “There will almost certainly be scope for revisiting the Tolmers area in future to assess the long-term impact of the redevelopment scheme and the policies pursued.”

Nick Wates is a specialist in community planning and design, and the author of The Community Planning Handbook (Earthscan, 2000).

Footnote: Other former Bartlett (then the School of Environmental Studies) students involved in Tolmers Square in a variety of ways included: Arthur Chesney, Lynne Farrow, Pedro George, Jamie Gough, Frances Holliss, Caroline Lwin, Andrew Milburn, Suzi Nelson, Paul Nicholson, Danielle Pacaud, Jo Ravetz, Barry Shaw, Doug Smith, Alex Smith and Merve Spragg. Staff members involved included Reyner Banham, Michael Edwards, Rodney Mace, Mike Macrae.

Close

Close