The theory and practice of ‘space syntax’ emerged at The Bartlett in the 1970s as a means to model the use of architectural and urban space scientifically.

Bill Hillier, at 32 years old, as Assistant Secretary of the RIBA in 1969. Credit: RIBA Collections

The paper came out at a point in which cities were becoming increasingly complex but when, it seemed, the grand plans of the post-war modernist era were giving way to more piecemeal forms of development, shaped primarily by regulations and zoning principles rather than long-term ambition.

Hillier and his colleagues proposed analysing spatial patterns using mathematical representation of the relationship between spaces within a system and setting this against data on patterns of space usage, to better understand the people and societies that shape them. They believed that by observing and quantifying the movement and interaction of people and their density, distribution and behaviour within an area, you could understand the impact of spatial configuration on social phenomena. These lessons could then be used to simulate the impact of changes to the built environment and therefore design buildings, public spaces and cities better suited to our needs. Much of this thinking was captured in a 1994 episode of the BBC’s Tomorrow’s World featuring Hillier’s space syntax analysis of the design of the North Peckham Estate in London.

Looking back, Hillier argued that architecture in the 20th century seemed to be far more concerned with how buildings and environments should be, rather than how they actually were, and the field tended to draw its lessons from other disciplines – from psychology to engineering – rather than from within itself. (Hillier summed up this idea that cities grow, evolve and adapt, and that scientific observation is needed to deduce their fundamental rules, in a Guardian article published in 2004, when he said: “I wouldn’t design a new city, I’d grow one.”)

Seeing cities as they are

The Space Syntax Laboratory at The Bartlett – originally the Unit for Architectural Studies – where this field of study was invented, sought to rectify that and, today, this way of thinking can be found in universities and firms around the world – enabled further by the increasing power of computer technology. The research group that Hillier was instrumental in founding is a leading voice in the field, examining the human dimension of space as well as advancing the use of technologies to help us visualise socio-spatial patterns. Collaboration is part of its remit, and the lab works with other Bartlett and UCL departments and disciplines, including anthropology, psychology, medicine and geography.

For example, a recent research project – Contested Cities – funded by the European Commission Horizon 2020 programme investigated the role of political, spatial and social factors in shaping urban segregation in Sweden and Israel. One of the project’s outputs, a film called Learning from Jerusalem uses space syntax methods to analyse some of the main changes to have taken place in the city over the 20th century.

Another project – a collaboration with the Mixed Reality Lab at the Nottingham University – looked to understand the impact on place and the quality of public experience of introducing large screens into civic squares. The research was carried out ‘in the wild’ with the London Borough of Waltham Forest throughout the London 2012 Olympic Games. Towards Successful Suburban Town Centres, a project the lab ran for three years, contributed to the policy debate on how to shape cohesive and vibrant communities in the suburbs, which is where the majority of housing growth will occur in England and Wales over the next 20 years.

There is also a continuous dialogue between the lab’s academic research and industry via its spin-off company, Space Syntax Ltd, which offers the expertise of the lab’s researchers to architects and urban planners across the world. Planning the redevelopment of Trafalgar Square is one such example. When a masterplan for the area was commissioned in 1996 by Westminster City Council and the Greater London Authority, calling for improvements in the quality of the public realm, Space Syntax Ltd – led by Tim Stonor – provided the initial analysis of pedestrian activity patterns, which highlighted two key issues: Londoners avoided the centre of Trafalgar Square and tourists failed to make the journey between Trafalgar Square and Parliament Square.

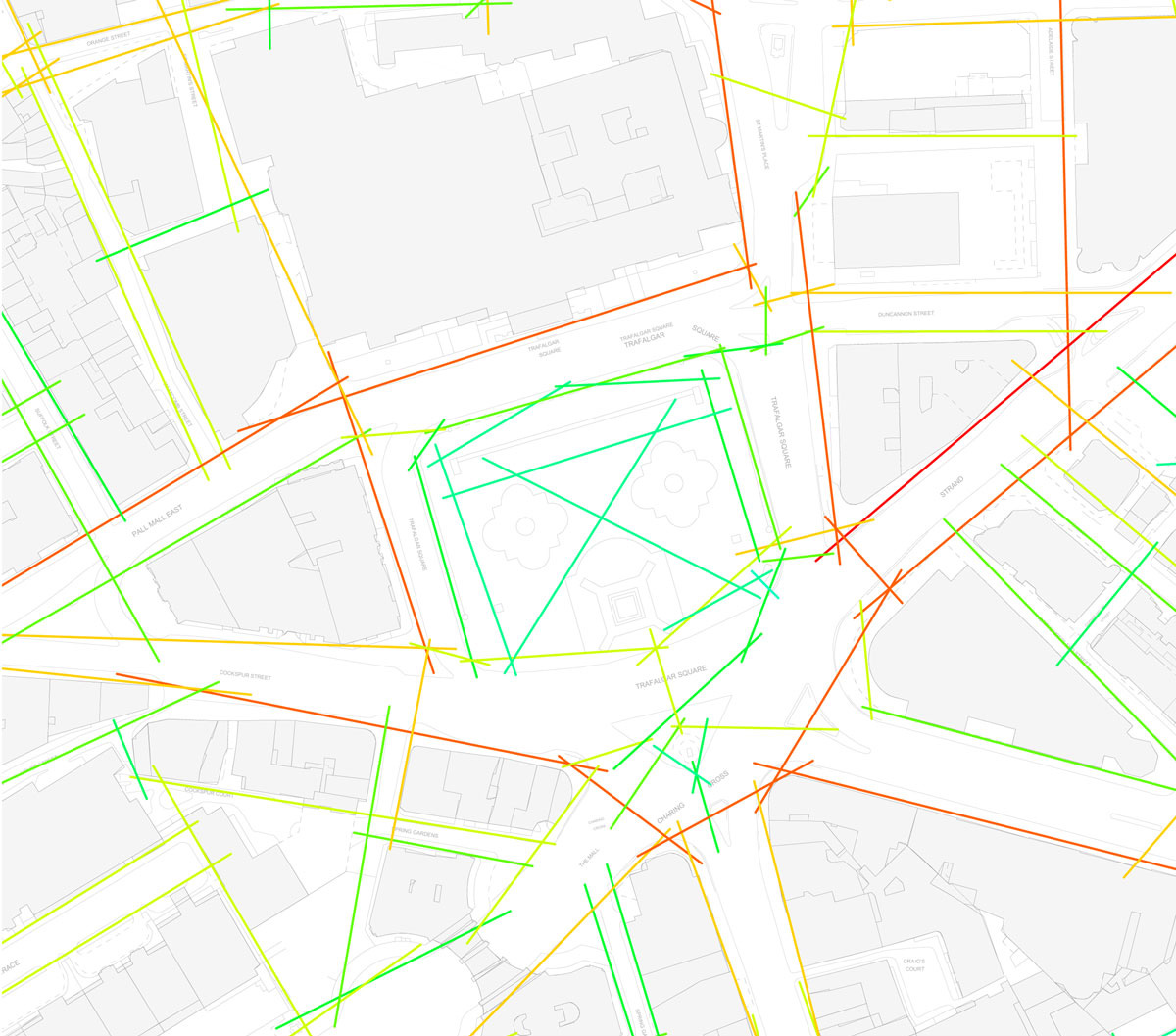

Spatial accessibility analysis of Trafalgar Square (form). Key spatial issues: Trafalgar Square is not spatially integrated into its surroundings. Credit Space Syntax Ltd

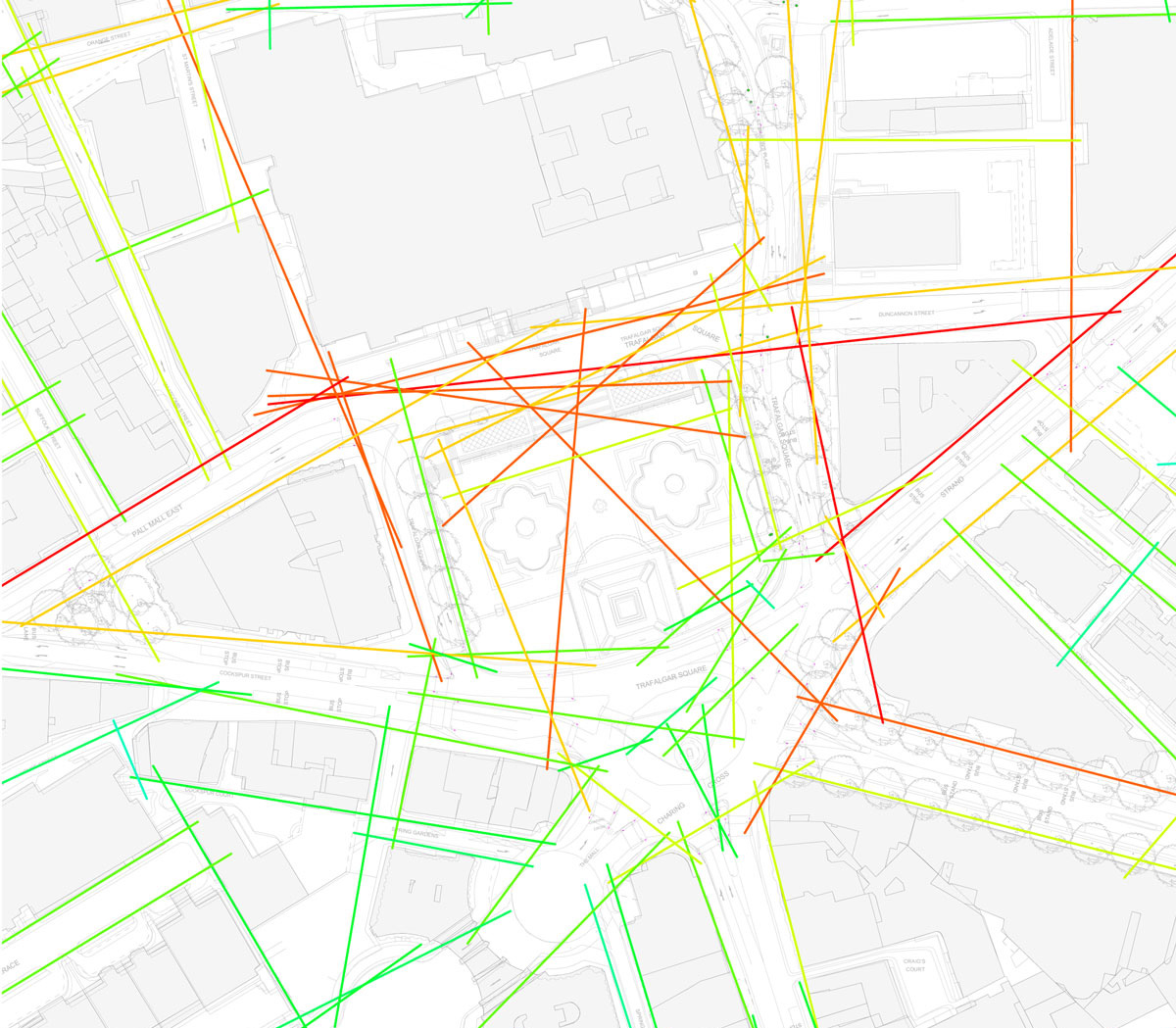

Test design recommendation for linking Trafalgar Square with its surroundings, including adding what is now the main central staircase. Credit: Space Syntax Ltd

Observation study of pedestrian movement and stationary activities (function) – red dots are stationary pedestrians; blue lines are walking pedestrians. Key functional issues: Evidence revealed Londoners avoided the centre of Trafalgar Square and tourists failed to make the journey between Trafalgar Square and Parliament Square. Credit: Space Syntax Ltd

How cities work

To date, space syntax has been used in a range of contexts: from analysing pedestrian flows, circulation and wayfinding within major London museums, improving nurses’ travel paths and natural surveillance in hospitals, and designing office working environments, to modelling the impact of new transit stations on cities and devising large-scale masterplans in China, Saudi Arabia, Spain and the UK.

The work of the lab and its offshoots (other companies and labs exist in the UK and worldwide) is fundamental to the theoretical development of the discipline, as work on real-world projects feeds back into the university’s knowledge base and vice-versa, helping improve its investigative and analytical capabilities.

Hillier continued to push the theory of space syntax forward, asking the questions that kept it relevant and evolving, pointing out in a 2016 paper, What Are Cities For?, that while space syntax explains how cities work, it does not explain why. “Cities are not designed things, but emergent processes,” he wrote. “To understand cities, then, we must understand the process of emergence and even more, the structure of emergence, and ask how and why the city, defined this way, reflects or shapes human experience and activity, and with what outcomes.”

Close

Close