The Prosperity Index for London is a ground-breaking initiative from The Bartlett's Institute for Global Prosperity rethinking what prosperity means with, and for, Londoners.

What does prosperity mean to people living and working in east London? What enables and what inhibits prosperity? How would action on prosperity change if communities set the terms, priorities and measures that policy-makers use?

These are the type of questions that The Bartlett’s Institute for Global Prosperity (IGP) has been exploring in east London for the past four years, working with citizen scientists and the London Prosperity Board (LPB). That work has informed what will be the UK’s first citizen-led Prosperity Index when it launches in May this year. The Index is a new way of understanding and measuring what matters to the prosperity of local communities.

Indicators and metrics are powerful forms of knowledge that shape how decision-makers recognise, understand and act on opportunities and problems. Questioning the concepts and assumptions that underpin what is measured is one of the ways in which the IGP works to improve evidence and decision-making about building globally prosperous futures.

“Co-producing knowledge with citizen scientists and local communities is a critical part of the IGP’s way of working,” says Saffron Woodcraft, Senior Research Associate at IGP. “Developing visions of prosperity with, and for, communities brings local priorities and lived experience into decision-making in ways that can highlight gaps between expert-led and local knowledge, capturing the things that matter in ways that are meaningful and allow for action.”

In London, this work has involved two pilot projects and 20 citizen scientists working to understand what prosperity means to people living and working in five east London neighbourhoods. In-depth qualitative research carried out in 2015 has been developed into a local ‘prosperity model’ that identifies the conditions that residents say are important for their communities to flourish. These include factors such as secure livelihoods, affordable housing, good-quality work, inclusion in the social and economic life of the city, and a voice in local decision-making, as well as individual health, wellbeing and opportunities.

The Prosperity Index for London is the first time the UK has had prosperity metrics based on a model and priorities identified by citizens and local communities. Credit: IGP

Revealing prosperity gaps

Over the past two years, IGP and the LPB have translated this local model into a set of 15 headline indicators designed to measure prosperity, as defined by local communities at the neighbourhood level. The IGP has developed a number of new metrics to reflect local priorities; these include indicators evaluating the quality and security of work and job satisfaction, rather than simply employment; measures of financial stress; a new method of calculating real household disposable income that accounts for tax, housing costs, utility bills and debt repayments, to offer a more realistic picture of the local living costs; and subjective evaluations of hope for the future and feelings of agency.

In 2017, the IGP and the LPB piloted a new Prosperity Index household survey of 750 households in east London to test both the new indicators and a small-area data collection method. The household survey data was then compiled into a Prosperity Index for London, making it the first time the UK has had prosperity metrics based on a model and priorities identified by citizens and local communities.

Woodcraft says that the Index compares the prosperity of individual neighbourhoods to the Greater London average and highlights the challenges around secure livelihoods, good-quality work, affordable housing and social and economic inclusion that are an obstacle to prosperity in east London. “Focusing on small-area data collection provides a granular picture of prosperity ‘gaps’ – spatialised inequalities that are often obscured by data collected at larger geographies,” she says.

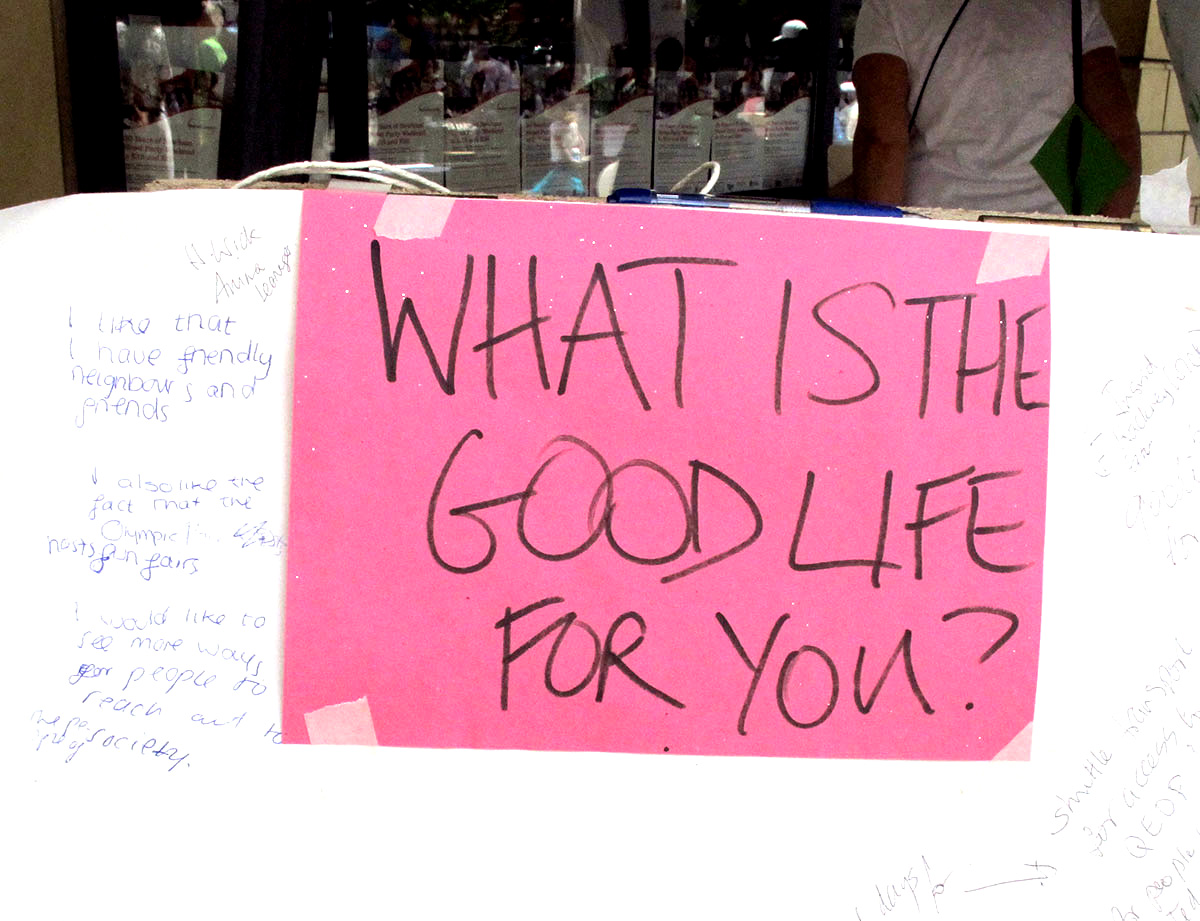

Collecting views on 'the good life' from local residents in east London. Credit: IGP

Context is key to prosperity

The IGP’s research in east London has challenged the conventional definition of prosperity as material wealth that dominates policy-making. Since the mid 20th century, this vision has driven a global development agenda focused on wealth creation, driven by economic growth and measured by rising levels of GDP. In this context, GDP has become the default measure of societal prosperity and policy-makers have pursued GDP growth as an end in itself rather than a means to improving the quality of peoples’ lives.

“The assumption that rising GDP would ’trickle down’ and lead to improvements in living standards, opportunities and wellbeing has stalled, and in some cases, reversed,” says Woodcraft, highlighting London as a case in point. “It is an extremely wealthy city, but one with stark social and economic inequalities that affect many people and how they feel about their futures.” Employment rates are more than 73% in London – the highest level since 1992 – yet, 1.3 million people living in poverty are in a working family, according to Trust for London’s London Poverty Profile in 2017.

IGP’s new Prosperity Index metrics examine this gap – investigating the tensions between employment and work quality, insecure and low-wage work, high costs of living and low-levels of real household disposable income, levels of local wellbeing and feelings of control over the future. Its pilot research in east London has identified a gap between prosperity as a policy goal and prosperity as a lived experience, and demonstrated that working with citizen scientists and communities to map out local conditions, priorities and pathways, can change policy responses and develop new, concrete forms of action on prosperity.

An example of flyposting in east London. Credit: E. Starling

IGP’s collaborative way of working with citizen scientists and multi-sector partners is being developed in other parts of the UK and internationally, in Kenya, through the RELIEF Centre in Lebanon, and through the KNOW programme in Havana and Dar es Salaam.

Saffron Woodcraft is Executive Lead and Principal Research Fellow of the UCL Institute for Global Prosperity's Prosperity Co-Lab UK (ProCol UK)

Close

Close