The case of Bajo Belén, Iquitos

Ethos Periodismo was born during the Critical Urbanism Studio. We are a group of urban practitioners (Aisha Aminu, Chauncie Bigler, Maheen Zakir, Natalia Meléndez Fuentes, Shaden Amr El Galaly) who question the forces shaping the urban built environment. This discussion is preliminary to open the door for the exchange of ideas which positively impact the political ecology of disaster mitigation, theory of uninhabitability, vulnerability of low-income populations in a climate changing world, and participatory urban policy.

The Narrative-Shifting Project

This project arises to acknowledge and understand the gaps surrounding the failed relocation of the Bajo Belén neighborhood of Iquitos, using three dimensions: enviro-political, socio-economic and psycho-emotional. To bridge connections between actors and encourage solutions which target the root of problems, we hope to disseminate clear information which pushes the perspectives of all actors. We build upon the work of Ciudades Auto-Sostenibles Amazónicas (CASA)––in charge of the Centro de Investigación de la Arquitectura y la Ciudad (CIAC) of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (PUCP), and various others, and hope to inspire creative policies and interventions which strengthen communities in the face of disasters.

A Word on Positionality

We are aware of the ethical issues implied in representing the voices of underrepresented groups, and we acknowledge our positionality in trying to surface alternative narratives of the people of Bajo Belén. Therefore, our sole aim for this publication is to pass on the extent to which the human factor has been ignored in the case of the relocation of Bajo Belén and propose more people-centric alternatives.

- What makes a place "uninhabitable"?

Conceptualising Risk and Resilience

Risk: According to its Latin etymology, ‘risk’ (‘risco’) as a concept is linked more closely to vulnerability than to danger (Definición.de). Thus, ‘danger’ is linked to the feasibility of harm or damage taking place, whereas ‘risk,’ is more about the possibility of something bad happening.Therefore, one can infer that this equation of possibility and probability is detrimental for those who are merely exposed to the possibility of, but not so much to the probability of something bad happening to them––communities such as Bajo Belén.

Resilience: The reality of increased weather extremes due to climate change will impact the farthest corners of the world. Governments, research institutions, and businesses are positioned with the authority to mitigate these challenges and protect our communities.However, examining who makes decisions relating to ‘resilience’ brings up several channels of enquiry such as: Who decides what it means to be ‘vulnerable’? Who should be protected (and how)? How much risk is too much risk? And “too much risk” for what or for whom? These decisions often have inherently political, social, and economic motives, and will result in very real impacts on communities.

- Bajo Belén as ‘Uninhabitable’. How did we get here?

Examining the history, actors, and narratives which led to the current state of affairs for Bajo Belén, Iquitos.

The neighborhood of Bajo Belén is located in the Amazonian city of Iquitos. Like many Amazonian resource-built communities, Iquitos has a unique geopolitical, economic, and social history. Following the rubber and oil booms and later, bursts, combined with conflicting housing policies and lacking infrastructure investments, Bajo Belén's current circumstance is a reflection of its deep history within this region.

In an effort to highlight the influential historical events, trends, and actors which have deeply impacted the circumstances of today's Belén, an interactive timeline has been assembled. (Link to An Interactive Timeline of Iquitos and Bajo Belén's History: https://time.graphics/es/line/315749 ) Follow the link to interact with the timeline; events are distinguished between governmental history (top) and social history (bottom).

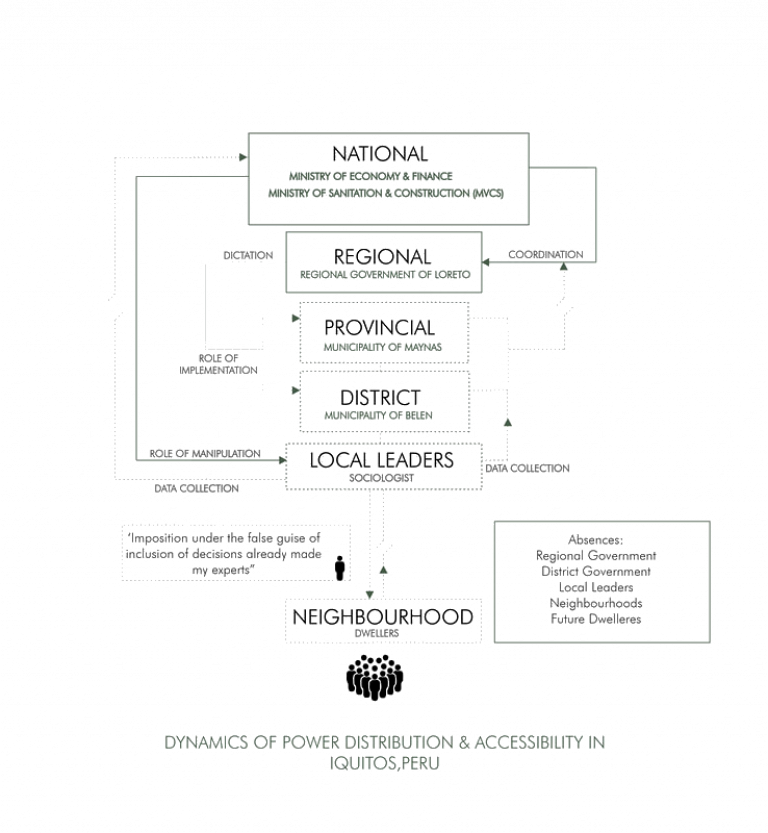

Dynamics of Power Distribution & Accessibility: Observing the political power dynamics influencing decisions in Iquitos, a hyper-centralized top-down approach is evident. The local government (including regional, provincial and district) has a fixed role of implementation; it exclusively follows the guidance dictated by the national government. Additionally, the distance at which decisions about communities are being made at the national level in far-away Lima, presents challenges for implementation at the local level.The Ministry of Housing, Construction and Sanitation (MVCS) is responsible for the design and implementation of housing projects, having strong agency over deciding what parts of cities like Iquitos are considered ‘vulnerable’ or not.

In 2014, the Peruvian congress passed Law No. 30291, allowing the MVCS to designate Bajo Belén as a high risk area for flooding, thereby institutionalizing the notion of the area’s ‘uninhabitability’. The Law also cites child malnutrition, crime, and impoverishment as conditions underlying the vulnerability of the community.

One important question lies in the extent of the relationship between the MVCS with the sociologists and local leaders. According to Silva (2015), MVCS hired sociologists to collect local data through participation and deliver it to the local government, and to serve as mediators between the ministry and the people of Belen. This tactic has often been used to make civilians accept decisions which have already been made by the ‘experts’, under the disguise of inclusion and participation.

- Analyzing the Projects: Belén Sustainable (2013) and Nuevo Belen (2014)

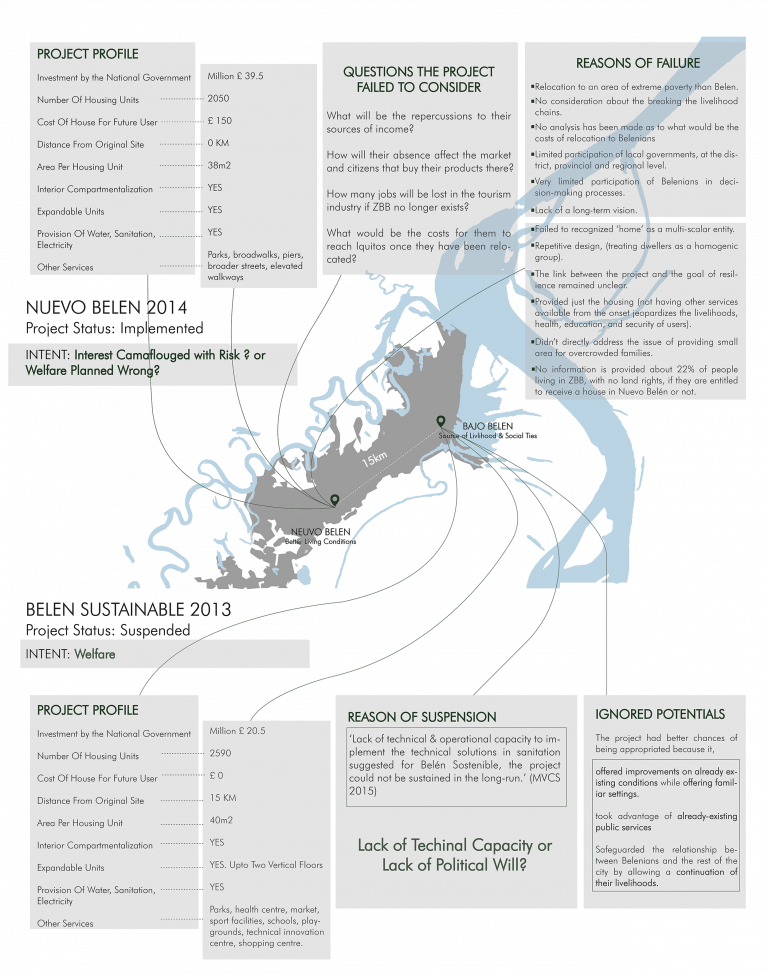

The facts of the two consecutive projects of Belen––upgrading and relocation––are highlighted through an examination of the intentions of the institutions behind the resettlement and upgrading projects, along with the discourses which were left out of discussions and the speculated reasons for failure.

Belén Sustainable (2013): The Peruvian government's first attempt to intervene in Bajo Belén was an upgrading project known as Belen Sustainable. This project was suspended in 2014, with the authorities citing increases in future flooding combined with a lack of technical and operational capacity of the government to implement the technical solutions on site. This lack of institutional capacity and funding cited should be examined further.

Nuevo Belén (2014): In the aftermath of Belén Sustainable and the Peruvian Government’s institutional unwillingness to further explore on-site upgrading, the municipality of Belen decided to resettle 13,385 inhabitants of Bajo Belén to an area 15km away, in the neighbouring municipality of San Juan Bautista. By relocating residents, the project of Nuevo Belén failed to include the community in the design process, as well as account for the residents’ socio-economic needs and connection to the site of Bajo Belén. Better recognition of the actual needs of the residents will be more efficient in the long term for the community.

The situation in Bajo Belén, Iquitos has reached an impasse, where the community does not want to move and is not listened to; and where the authorities and other stakeholders have their own agendas, also unable to transmit their limitations. The relocation to Nueva Ciudad de Belén has generated further tensions. The long-standing hostilities and failures to communicate remain unresolved.

- Tracing the Impacts of Narratives: Three Dimensions

The narratives of uninhabitability, vulnerability, and risk are analyzed through the lenses of three dimensions which impacted Bajo Belén’s current situation: enviro-political, socio-economic, and psycho-emotional. This analysis provides implications for climate change and disaster risk management, economic development and maintenance of livelihoods, historical adaptation to nature, and ethics of care.

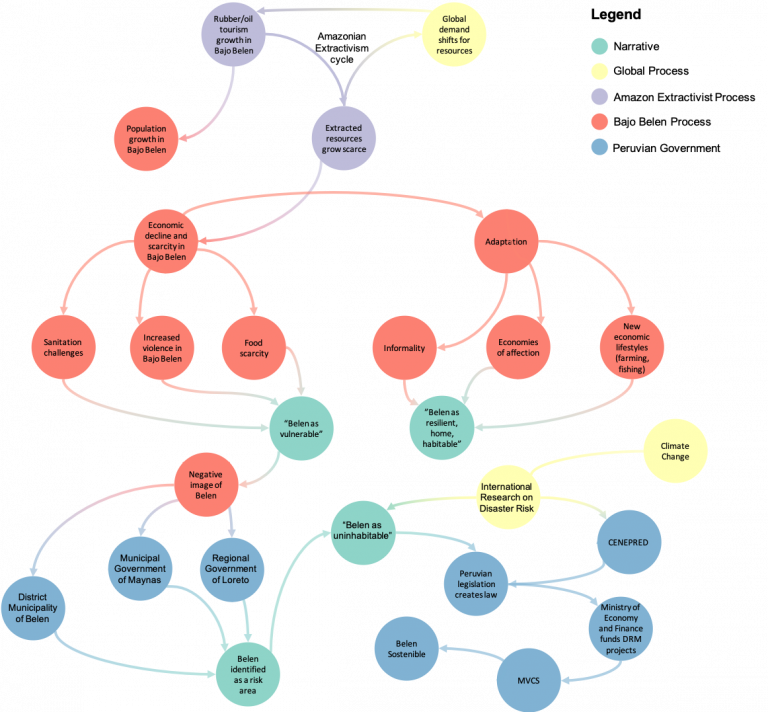

In an exercise to demonstrate the flows of the three narratives dominating this case, a mapping exercise was conducted (pictured below). The three narratives are presented centrally in turquoise, with flows contributing to and influenced by them being surrounded by global processes (yellow), local processes (red), and governmental activities (blue).

- Enviro-political dimension: Impacts of Climate Change

When do natural phenomena become habitability risks?

For the residents of Bajo Belén, seasonal flooding is a reality of life. Both natural and anthropogenic climate shifts can greatly influence life in harsher landscapes such as these. The way decisions are made around these factors are greatly subjective. This requires a deeper understanding of the narratives around the relationship between natural forces and the authoritative capacities of political powers.

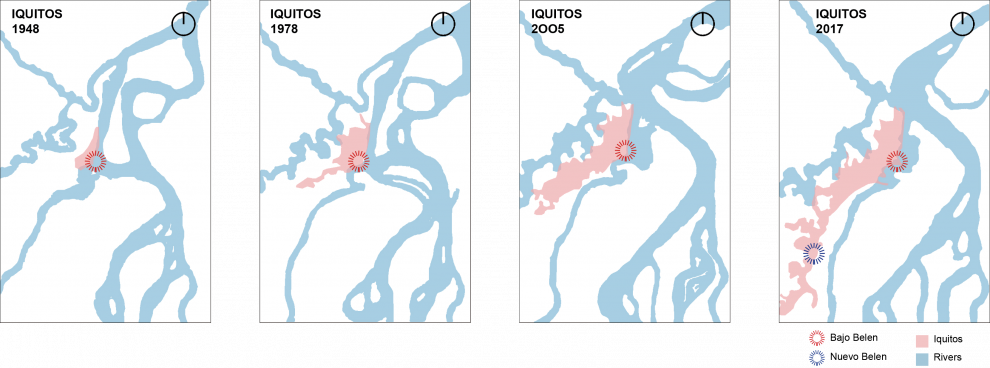

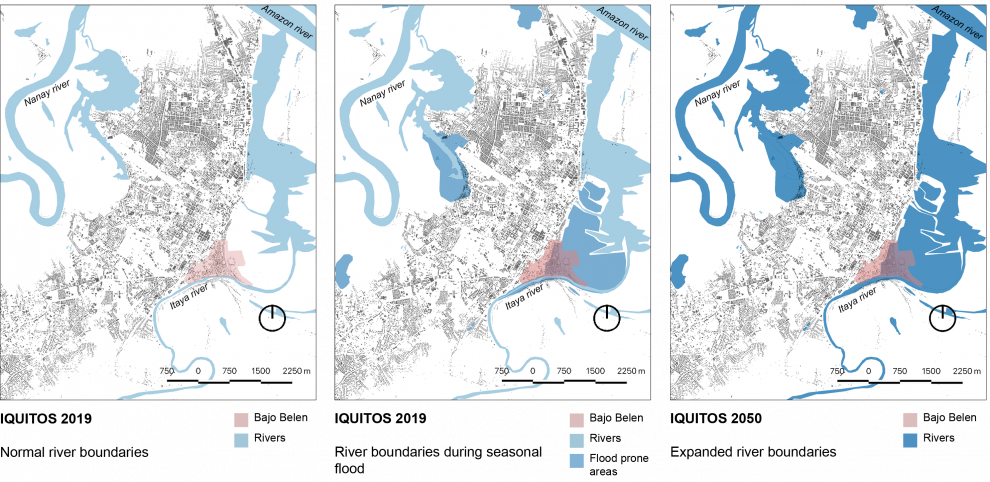

Spatial and historical context of changing river courses around Iquitos (Source of Maps: CASA (2017), ‘Preventive Population Resettlement and Climate Change in the Amazon)

It is a natural phenomenon for rivers to change course, to break into tributaries or to merge into one another. This has been the case for the river Amazon and the Itaya since 1948. Iquitos started as a small settlement by the river Itaya, and over the years, it had grown in a linear fashion, southwards, following the course of the river. While the seasonal floods currently affecting Iquitos are a natural phenomenon, the city is expected to have some of its parts (Bajo Belén included) underwater by 2050 as a result of rising sea levels and changes in the courses of the river Amazon and Itaya.

What has been missed in climate change decision making?

The notion of risk and disaster management, fuelled by international awareness and discourse of climate change, prompted the government of Peru into pre-emptive action by deciding to relocate the citizens of Bajo Belén to Nuevo Belén before 2050 (CASA, 2017). However, in being pre-emptive, the government did not take into account the probability of expected and unforeseen risks, nor the place identity and meaning of Bajo Belén to its residents and Iquitos as a whole.

Based on scientific forecasting protocols set up by Forecast Based Financing - FBF (an agency of the International Federation of Red Cross and Red Crescent Societies, German Red Cross and the Climate Centre), Iquitos’ Bajo Belén FBF report analysed the Amazon river danger level using historical data of 30 years at the Tamshiyacu station in Iquitos. Impact information from the Civil Defence Institute (known in Spanish as SINPAD) was analysed for three most extreme events affecting Punchana and Belen districts (Forecast Based Financing - FBF, 2019).

As of 2017 the probability of exceeding the danger level of 118.5m was less than 10% (Forecast Based Financing - FBF, 2019).

As of 2017 the probability of exceeding the danger level of 118.5m was less than 10% (Forecast Based Financing - FBF, 2019).

Therefore along with the danger level considerations, decision making for relocation did not take into account the meaning of Bajo Belen to its residents beyond its spatial aspects. Focus was on mitigating risks without considering the emerging risks that the very act of mitigation would create (CASA, 2017).

- Socio-economic dimension: Factors influencing resilience

Bajo Belén is often viewed by outsiders and decision-makers through a lens of its socio-economic shortcomings. Statistically speaking, it is regarded as one of the poorest areas of both Iquitos and Peru with a relatively high percentage of children malnourished (35%), high rates of school drop-outs, presence of crime and the highest rate of family violence (MVCS, 2015). Despite these pressing challenges, its positive influence both internally and externally are often disregarded. The perceived vulnerability of the community is explored against its economic strengths and resilience.

How does Bajo Belen contribute to Iquitos’ economy?

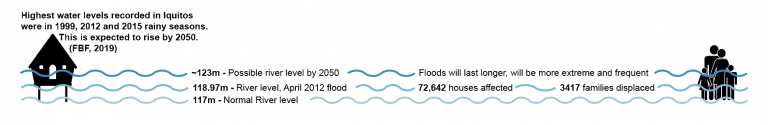

Bajo Belén is home to the Mercado Belen––the oldest, largest, and most diverse market in the city. With 75% of the residents of Bajo Belen having economic ties to the market, this establishes the area as a central hub and vantage point for the city of Iquitos (CENCA 2017).

According to the Our Cities Programme (Programa Nuestras Ciudades, PNC – MVCS), in 2015, the main economic activities conducted in Bajo Belén were commercial (55%), generally carried out by family breadwinners. Second to these are other activities (29%), followed by construction (8%), agriculture (6%), and last, livestock (2%) (CENCA, 2017: 63).

Another point of contribution to the economy of Iquitos is its positionality as a tourist destination both in the region as well as in the country. Bajo Belen is a point of interest in Iquitos and Peru among photographers, tourists and the media; tourists take excursions to experience the Belén market and indulge in exotic products.

Belén market greatly contributes to the city of Iquitos as well as to the Peruvian Amazonian region. In particular, the market concentrates the agricultural production of the area as well as riverside forest production. In addition, it provides goods that are hard to make or obtain, such as turtle meat and river fish (Gálvez Mora & Rochietti, 2015).What daily activities sustain the lives of the residents? How does this contribute to their resilience?

Another layer of internal economic activity is the vibrant social economy, which includes processes of exchange beyond monetary value. Networks of residents based on kinship and an ‘ethics of care’ provide opportunities to sustain life in the community, as services, knowledge, and items are given as gifts (CASA, 2017). These ‘economies of affection’ provide a means for the community to cope with the realities of life in a high-flood zone.

Common to Amazonian river communities, the ‘amphibious’ nature of Bajo Belén means residents demonstrate high levels of adaptation to the persistent patterns of flooding. Throughout the year, economic and social activities are influenced by the height of the river, as periods of flooding are met with the use of boats to exchange goods and services as well as increased fishing activities. This adaptation has implications for any plans to resettle the community, as the community’s demonstrated resistance to relocation is centered on their location of livelihoods.- Psycho-emotional dimension: What and who is missing from current portrayals of Bajo Belén as informal and uninhabitable?

An often neglected discourse around informality and relocation, psycho-emotional elements unveil what and who is missing from the current narratives surrounding Bajo Belén.

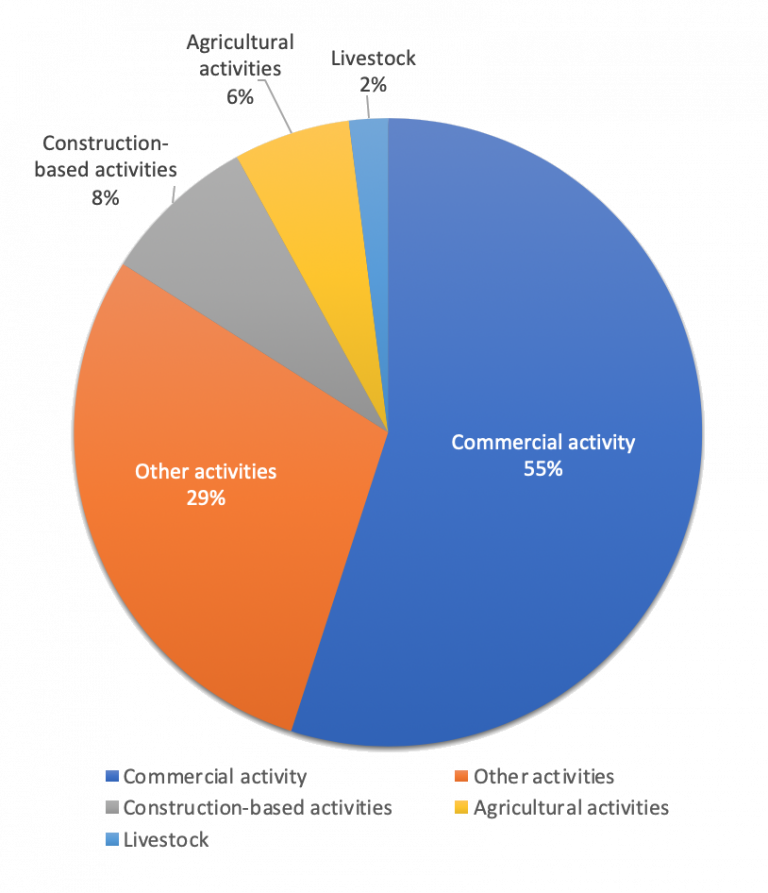

Decisions about communities often lack a basic understanding of central elements of their lives. Elements such as: community support networks, the irreplaceability of cultural heritage, sense of belonging and identity (Adger et al., 2011), and community traditions and beliefs. These elements are explored in further detail below. The following diagram shows the narratives surrounding the community of Bajo Belén, which are “Belén as uninhabitable”, “Belén as vulnerable”, and “Belén as resilient”.

Narrative #1: Belen as 'Uninhabitable'

“What does he think, that we are not human beings? Just because he has the money he can ridicule the poor? Well, he is wrong.”––Belén market merchant, and Bajo Belén resident, about Iquitos mayor’s inaction with regards to waste management (minute 01:39: http://panamericanatv.pe/buenosdiasperu/nacionales/239779-iquitos-vecino... )

As per the 2007 census, between 60% and 80% of Iquiteros define themselves as Indigenous or of Indigenous ancestry (INEI, 2009), and that percentage is known to be even higher in Bajo Belén. Given such high Indigenous identification in the area, it is essential to acknowledge indigenous traditions and knowledge in Bajo Belén. Therefore, declaring Bajo Belén as 'uninhabitable' counteracts indigenous culture and traditions.

In this line, defining a place as ‘uninhabitable’ entails that those who reside there are less human, or subhumans (Simone, 2016; Woods, 2019; Escobar, 2019). In this view, the human factor of the inhabitants of an area are completely ignored. Their lifestyles, livelihoods, traditions, attachments to the place, and ancestral roots to the environment must be understood.

In the case of Bajo Belén, this subhumanization has led to an unwillingness to understand on the part of most external actors. However, when one has a closer look at the community, one begins to grasp that the undermining ‘uninhabitability’ narrative is nothing more than a product of imposed structures of cultural supremacy.

Historically in the Amazonian context, imposed structures such as land tenure (Desmaison, 2018: 53) are incompatible with how Indigenous Peoples conceive their relationship with nature. Indigenous Peoples therefore live trapped in a vicious cycle where they are asked to abide by a system they do not agree with in the first place.

For the people of Bajo Belen, dwelling transcends walls and housing. It is connected to nature at intimate levels, which makes living in contact with nature a priority. As shown by their seasonal adaptation to flooding, the community adapts in order to maintain this connection.

Examples such as the Belén Festival––sponsored by the Gesundheit Institute––try to break the stereotyped notion of Bajo Belén as uninhabitable though an annual clown festival that enhances the neighborhood’s vitality, character and people. For an ethics of care approach, professional clowns visit Bajo Belén for a few days each year to bring visibility to those who have been invisibilized by prejudice and appropriated narratives. To see more about it, you can visit: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sqwrRnAMPJ4

Narrative #2: Belen as 'vulnerable'

“What is impossible to conceive; what is horrendous; what is pathetic, are the unsanitary conditions in which they live” (min 11:07), “residents have no right to have their children live under such conditions” (min 11:13), “the fact of being poor does not mean you have to be dirty” (min 11:21), “they are living like animals” (min 11:42). Such undermining and misleading caricaturization renders them all the more vulnerable.– a Limean TV host (Video link: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SS8me5CIRvA)

In various sources, Belén is depicted as weak, unsanitary, and helpless. Outsiders conduct cleanups, slum tourism is rampant, and institutional neglect is repackaged as a community which is derelict: ignoring skills, strengths, and agency.

The mediatization of the division of Bajo Belén, with the subsequent positive narratives about Nuevo Belén, and the negative depiction of Bajo Belén across national and local media outlets has contributed to the residents of Bajo Belén with an even more negative image. The general narrative is blaming the poor for their poverty.

Time and again, the actions of Bajo Belén’s residents against unsanitary conditions in which they have to live are under-reported by media outlets. The community has shown its unconformity and impassivity with regard to the conditions in which they are living. Instead, efforts of external actors to clean the area are widely present throughout different media outlets. The value of these external endeavors notwithstanding, the sole televization of this event puts forward a Messianic narrative, whereby residents in Bajo Belén are only able to clean up if an external force comes to lead the way.

Nevertheless, what this mediatic line of action does is to burden individuals with responsibilities and services that should be provided by the government. As a matter of fact, the unsanitary conditions of Bajo Belén are more the result of a failure in municipal garbage collection and management, than of the residents’ alleged insalubrity. And, on top of that, the fact that the community still wants to live there, despite the unhealthiness of the place, can be interpreted as a mode of resistance, and proof to their firm determination to lead a life close to the river.

Narrative #3: Belen as Resilient

Due to extraction and urban development of the Amazon (colonization, resource exploitation, and economic development), its inhabitants have adapted to this by establishing themselves only partially in urban areas, never relinquishing their connection and life near nature or within nature, leading to constant mobility and multi-sitedness (combining production activities with labor in both rural and urban settings) (Desmaison et al. 2018: 151). Nevertheless, our acknowledgement of their resilience throughout time cannot lead us to think that, no matter the climatic conditions, adaptability is always possible (Simone, 2016: 137).

In the specific case of Bajo Belén, one of the main drivers of their resilience have been strong community bonds. These are the mechanisms of community assistance on which the people of Bajo Belén rely in order to survive or confront daily challenges (Desmaison, 2019: 62). The relevance of these support networks notwithstanding, relocation and resettlement interventions tend to ignore the networks of communal support that exist within communities.

A part of such strong community bonds, are the ‘economies of affection’; a social system that transcends the visible economic aspects to form broad networks of social support. (Desmaison, 2018: 100). These vital and often ignored economic processes are increasingly impacted by climate change, with increased flooding decreasing the land available for growing crops (Ibid.).

The structures underlying economies of affection; emotional and communal bonds, solidarity, altruism, and collective work, all create powerful mechanisms for peoples in the Amazon to confront climate change (Ibid.). Despite the importance of these social networks and traditions in the lives of the people of Bajo Belén, most narratives about them ignore these, only focusing on detached-from-reality, uninformed stereotypes.

A special mention should be made to women in Bajo Belén, who contribute immensely to the resilience of their communities. In addition to their role in economies of affection, families (especially women) use home gardens to grow fruits and other food items to support the household’s economy (Wrinkle Prins & De Souza, 2005: 112). In line with other omissions in the design of Nuevo Belen, reliance on home gardens was completely ignored.

For further information and details on the psycho-emotional components regarding the people of Bajo Belén, you can view this document: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1zaPhy3pKbV44ivu5rKoZLYoF5ESPxSapGIEfqDbmZYk/edit#

Here follows a list of the videos supporting the information above:

Mediatization of the division of Bajo Belén over remaining or relocating: https://elcomercio.pe/peru/loreto/belen-dividido-quieren-reubicarse-otros-349636-noticia/

Positive narratives about the relocation area of Nuevo Bajo Belén: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=oSsXca9J8Ek

Negative mediatic depiction of Bajo Belén: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SS8me5CIRvA

Actions undertaken by Bajo Belén residents to fight the unsanitary conditions of the River: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=c1EXs3PEOwU

Unconformity and passivity of the residents over authorities inaction: http://panamericanatv.pe/buenosdiasperu/nacionales/239779-iquitos-vecinos-furiosos-lazan-basura-casa-alcalde-belen

Messianism or efforts of external actors to clean the area: https://es.aleteia.org/2018/02/19/el-angel-de-la-amazonia-que-devuelve-belleza-a-los-rios-en-peru/

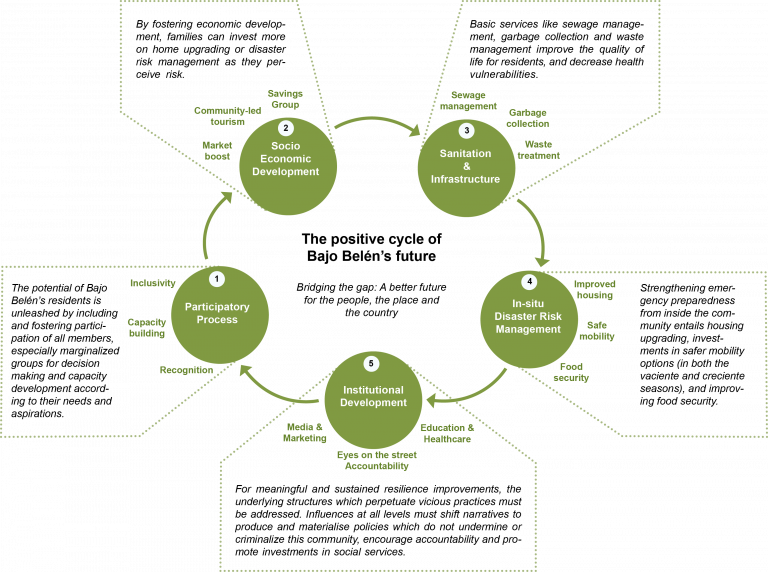

- Proposed Alternative: The Positive Cycle of Bajo Belén's Future

After assessing gaps in the narratives which led to the present state of affairs, we propose a shift towards a positive circle which will be more beneficial to all stakeholders in the future. The shift formalizes the residents of Bajo Belén as decision-makers and actors in their own development.

Narrative-Shifting: As observed, the conventional thinking in the development sector is majorly characterized by assumptions and rationalizations that underpin long-held hidden prejudices. Thereby, an additional recommendation surrounding the case of Bajo Belén, and any similar climate-related relocation, is to re-examine the preconceptions that undermine decision-making. Such preconceptions include:

Failing to understand the meaning of ‘Bajo Belen’ to its residents beyond its spatial aspects and their contribution to the city.

Not being clear about the implications of ‘hazards’ other than flooding.

Failing to recognize the link between vulnerability and disasters in assuming disaster risk management (DRM).

Presuming disaster risk mitigation in the form of relocation to Nuevo Belen.

Not focusing on the structural causes of powerlessness that result in insecurity, deprivation and creation of slums and accusing the poor of instigating these.All of these complacent indifferences to underlying realities do not only build narratives of inhabitability and vulnerability around communities, but also show how different stakeholders play a role in perpetuating these discourses through intersecting preconceptions. This emphasizes the need to think more deeply about the root mis-conceptualizations of decision-making processes.

Discussion and Conclusion

Given the conflicting narratives between external actors at different levels and the daily realities of Bajo Belén’s residents, the assumptions underlying themes of risk, resilience, and vulnerability must be tested and examined in planned relocations. In the case of Bajo Belén, issues such as sanitation infrastructure, housing upgrading, improved connectivity and road infrastructure were passed up for a relocation project which does not fully acknowledge the tangible ‘everyday’ risks which residents of the community are faced with.

Strategic interventions into communities such as Bajo Belén must seek to benefit the residents with recognition of agency, improved quality of life, and strengthened infrastructure––thus becoming interventions with communities, which indicates an equal footing. The adaptive nature of residents settling in high-risk zones means that plans to relocate do not target the root causes of problems, or the biases which influence definitions of “vulnerability” and “risk”. The determined choice to remain in Bajo Belén is grounded in the economic opportunities and persistence of livelihoods, as well as vital social networks. The proposed alternatives must be constructive, healing, and respectful to residents, and must seek to keep their strengths intact while addressing the points of vulnerability identified by the community. That is why our proposed positive cycle of strategies, that includes participation, socio-economic groups, sanitation and infrastructure, in-situ disaster risk management and institutional development, is deliberately maintained as a flexible framework and a threshold for affirmative actions to maximize its impact and avoid the traditional over-optimism attached to typical approaches.- Bibliography

Alexiades, M., & Peluso, D. (2016) La urbanización indígena en la Amazonia. Un nuevo contexto de articulación social y territorial. Gazeta de Antropología, 32 (1), artículo 01.

Adger, W. N., Barnett, J., Chapin III, F., & Ellemor, H. (2011). This Must Be the Place: Underrepresentation of Identity and Meaning in Climate Change Decision-Making. Global Environmental Politics, 10, 1–25.

Cajo Charpentier, V. F. (2016) Percepción socio-ambiental de la población (Zona Baja de Belén), reubicada en el Varillalito, Carretera Iquitos-Nauta. Km 13.5. Distrito de San Juan Bautista, Región Loreto. Tesis doctoral. Universidad Nacional de la Amazonía Peruana (UNAP): Iquitos, Perú.

CENCA (2017). Informe tercer producto estudio de evaluación del potencial económico y social del ámbito de estudio y el área de influencia de la Nueva Ciudad de Belén. Lima Perú. Peru – Program Nuestras Ciudades, pp.63-66).

Centro de Investigación de la Arquitectura y la Ciudad (CIAC) (Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú), (August, 2017). Reasentamiento poblacional preventivo y cambio climático en la Amazonía (CASA (Ciudades Auto-Sostenibles Amazónicas) Working Paper n.1). Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú: Lima.

CASA (2017). Working paper: Reasentamiento Poblacional Preventivo y Cambio Climático en la Amazonía

Desmaison, B, Boano, C, & Astolfo, G. (2018). CASA [Ciudades Auto-Sostenibles Amazónicas]: Desafíos y oportunidades para la sostenibilidad de los proyectos de reasentamiento poblacional preventivo en la Amazonía Peruana. Medio Ambiente Y UrbanizaciÓn , 88 Pp. 149-176. (2018), Medio Ambiente y UrbanizaciÓn , 88 pp. 149-176. (2018).

Escobar, A (2019). Habitability and design: Radical interdependence and the re-earthing of cities. Geoforum 101 (2019) 132–140.

INEI (2009). “Perfil Sociodemográfico del Departamento de Loreto”, Censos Nacionales de 2007: XI de Población y VI de Vivienda (INEI, UNFPA, UNDP). Lima: Instituto Nacional de Estadística e Informática.

Paz Campuzano, O. (2015, April). Belén está dividido: unos quieren reubicarse y otros no, El Comercio: Lima, Perú. Retrieved from: https://elcomercio.pe/peru/loreto/belen-dividido-quieren-reubicarse-otros-349636-noticia/

Forecast Based Financing (2019). Flooding in the Peruvian Amazon Region. Retrieved from https://www.forecast-based-financing.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/01/Brochure-Tecnico-Iquitos-english.pdf (Accessed 9 Nov, 2019)

Gálvez Mora, C. & Rochietti, A. (2015). Patrimonio cultural del Perú. Humanidad andina (Debates). Eduvim: Buenos Aires.

Marina De Guerra Del Perú (Dirección De Hidrografía y Navegación). (2015, July). Riesgos Naturales Que Afectan El Barrio Bajo De Belén

MVCS, 2015. Estudio de preinversión a nivel de perfil del programa de inversión pública “Habilitación urbana para la reubicación de la población de la zona de Belen, distrito de Belén, provincial de Maynas, departamento de Loreto”

Simone, A. (2016). The uninhabitable?: In between collapsed yet still rigid distinctions. Cultural Politics, 12(2), 135-154.

Woods, M. (2019). Hospitality; or, A Critique of Un/Inhabitability. Cultural Politics: An International Journal, 15(2), 202-222.

Wrinkle Prins, A., & de Souza, P. (2005). Surviving the City: Urban Home Gardens and the Economy of Affection in the Brazilian Amazon. Journal of Latin American Geography, 4(1), 107–126.- Contact us

Close

Close