Ελληνικά

under the aegis of the Canadian Institute in Greece and the Hellenic Ministry of Culture

A set of abandoned hillslope and cross-channel terraces near Xeropotamos. Photograph by A. Bevan.

One particularly characteristic feature of Mediterranean landscapes is their often complex and extensive systems of fields, trackways and terraces. These are all long-term, non-mechanical investments (sometimes called 'landesque' capital) that usually have an anticipated use beyond the current farming cycle and/or over many human generations (it could be argued that certain long-lived orchards also fall into this category).

Despite their obvious importance in the past, and clear relevance to modern concerns with sustainable agriculture, the social context in which these structures emerge is not clearly understood. Standard explanations for the appearance of terraces, for example, invoke explanations of demographic pressure, increased territoriality, and the need to improve landscape productivity by bringing what are otherwise perceived as more marginal, sloped landscapes into cultivation. On Antikythera, as part of a discrete sub-project funded by the UK AHRC Landscape & Environment research scheme, we have been exploring these issues in greater detail, through a combination of archaeological and geoarchaeological prospection, ethnographic study and statistical analysis.

Terrace construction techniques: (above) a drystone riser made of large Neogene limestone slabs filled with smaller stones, and (below) a collapsed riser made entirely of even-sized Neogene cobbles with at least two buried soil horizons behind it. Photographs by J.J.P O'Neill and B. Hassett.

Many of the usual analytical problems associated with understanding the relationship between landscape modifications, such as terraces, are less troublesome on Antikythera because of its episodic settlement history which makes it easier to link terrace construction with particular phases of the island's past. We are trying to understand these features by combining five related approaches:

- A complete digital mapping of the terrace systems on the island drawing on a combination of modern Quickbird satellite imagery, aerial photos from 1944 when the island's terraces were still in general use and an extensive programme of ground truthing. This dataset is available on the downloads page and, to our knowledge, provides one of the only datasets of its kind in the Mediterranean.

- Geoarchaeological prospection of key locales where we might uncover multiple phases of terracing, with particular attention to terrace construction techniques, erosion episodes, and variable soil fertility.

- Comprehensive archaeological survey which offers us a picture of the surface pottery associated with these structures and allows us to isolate parts of the landscape that might have relatively uncomplicated terrace phases worth further detailed study.

- Ecological modelling of the island's vegetation communities and how they relate to major human investments. Particular concerns include the identifcation of relict crops on the now abandoned terrace systems, understanding patterns of maquis recolonisation, as well as the effects of erosion.

- Ethnohistorical research through interviews with the island's older remaining inhabitants and consultation of the extensive 18th-20th century historical archives for Antikythera. These methods seek to address when and how terraces were built, who owned them, what crops were grown there and what impact terrace-building episodes had on the overall productivity of the island.

Our mapping of all terraces is now complete (with a final round of ground-truthing to be done in spring 2008) and suggests that there are about 12,000 of these structures across the island. The most extensive period of terracing is probably also the most recent one, with significant activity throughout the 19th century. Stratified terrace soils in several areas however point to earlier episodes, of which some seem to be Late Roman in date while others may even be as early as the Bronze Age to judge from the circumstantial evidence of associated pottery. We are planning a targeted programme of radiocarbon and OSL dating in the spring to verify and build on these observations.

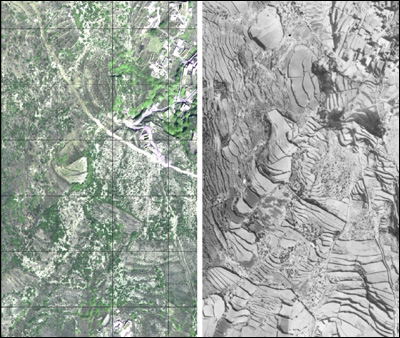

The same terraced landscape: shown by a Quickbird pan-sharpened image in 2004 after the terraces have mostly been abandoned (left, 100m grid shown) and on an RAF aerial photo in 1944 (right), when the island was last heavily under cultivation. Our terrace mapping makes use of both types of information along with intensive ground-truthing. Images courtesy of Digital Globe and the Aerial Reconnaisance Archive).

In addition, there are also clear correlations between bedrock and soil types and the propensity to build terraces, with a strong preference for investing more heavily in terraces on the Neogene marl limestone units. Likewise, there are several important examples of terrace systems that take advantage of the lee-side of large faulted zones, where cliff-faces provide shelter from prevailing sea-winds and create microclimates that enjoy a greater proportion of rainfall. Terraces and related investments also seem to have been important attractors in the landscape, even across demographic lows where the island may have been all but abandoned: more precisely, new colonists seem to return to localities with some previous human presence (as visible presumably by ruined, abandoned terraces etc.) to a degree which goes well beyond what might be expected if only broader environmental zones were being preferred. In other words, the sense of structured place that such relict features helped create is arguably a critical part of their long-term role.