Student blog - Bridgerton Unbuttoned: Sex, race and society in Netflix's hit series

1 April 2021

Evie Robinson, English Literature undergraduate student, blogs about the recent panel event where some of UCL's leading academics discussed Bridgerton’s portrayal of Regency life, society, sex, fashion and gender politics

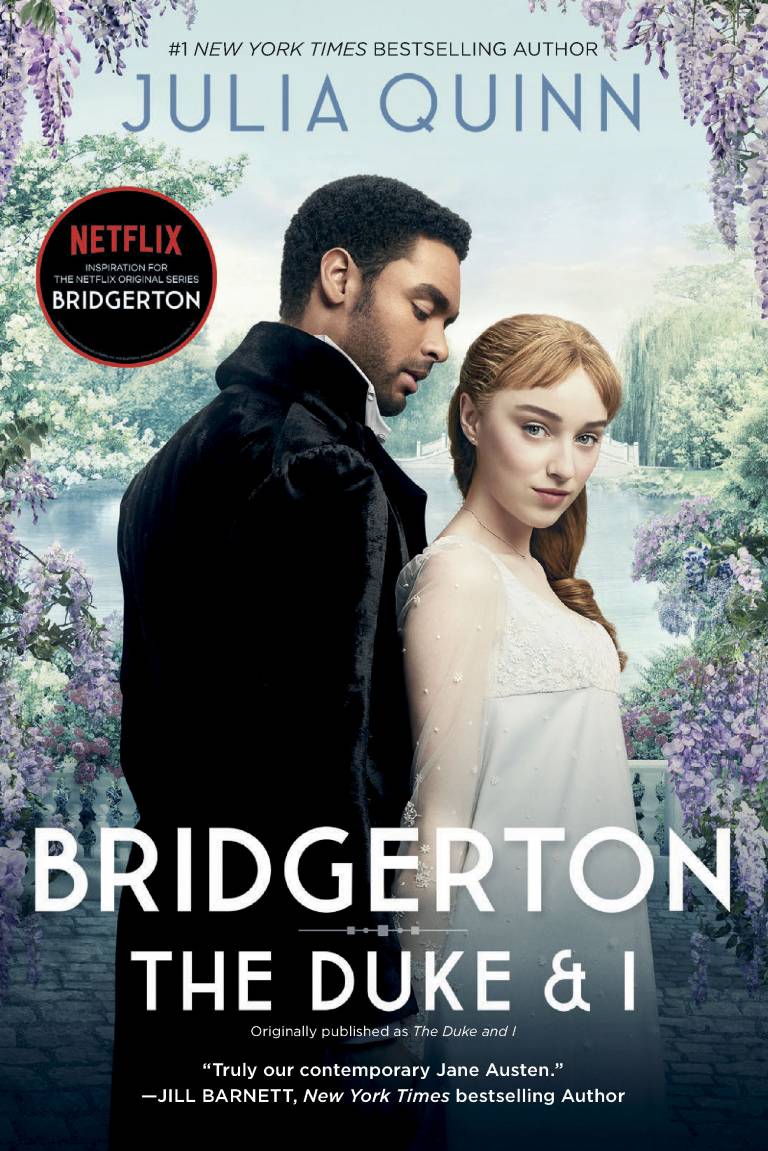

Since its arrival onto Netflix in December 2020, Bridgerton has captivated audiences across the globe through its depictions of 19th-century high society, with its marriages, balls and social scandals. It speaks to our contemporary society in many ways and, as such, has recently prompted discussion from two of UCL's most esteemed academics. John Mullan (Lord Northcliffe Professor of Modern English Literature in the UCL Department of English Language & Literature) and Stella Bruzzi (Professor of Film and Dean of the UCL Faculty of Arts & Humanities) came together in conversation to consider why Bridgerton has been such a success.

UCL students received the unique opportunity to hear some behind-the-scenes insights from John Mullan, who acts as historical consultant on Bridgerton, predominantly due to his academic specialism in early 19th-century fiction (especially that of Jane Austen). He was first consulted during the early stages of production and is then frequently tasked with reading scripts and identifying historical inaccuracies or anachronisms. It was fascinating to hear how the writing team working on Bridgerton both rely on and cast away different historical details. Providing anecdotal examples of changes he suggested, including smoking cigarettes, hunting wild boars and modes of address amongst members of the aristocracy, John Mullan shed light on the way he helped the team to determine what was possible for the show in terms of honouring historical context, highlighting the team's particular focus on the manners, formalities, restrictions and protocols of the day.

Having written extensively as an academic on costume and makeup in film, Stella Bruzzi shared her thoughts on the aesthetics of the show. Emphasising the idea that costumes are not clothes, Stella relayed that one of the central purposes of costume is to shed light on character and narrative; to interrupt narrative and bridge the gap between past and present. The costumes in the show seem to be largely aspirational rather than historically accurate, with 19th-century cut-outs but use of modern fabrics and colours to appeal to youngsters in the 21st century. Simple contrasts in costume help viewers to draw distinctions between members of high society. The Bridgertons, an economically and socially esteemed family with a long-standing and renowned reputation, dress in subtle and muted colours, sometimes with every family member dressed in a coordinated colour. The Featheringtons, on the other hand, are always dressed in aggressively bright and clashing colours, seemingly a family on the social climb who have recently come into 'new money', as Stella suggested.

Perhaps the most controversial yet enticing element of Bridgerton is its exploration of sex and bodies, notably the comic effect of how little Daphne is told by her mother about sex and marital life, and the way in which the depiction of Simon, (or the Duke of Hastings), speaks to contemporary audiences the most, replacing a historically accurate appearance or physique with a prompt of attraction from the modern eye. The show's enjoyment of human flesh is one way that it makes virtue of the freedoms it takes with historical accuracy, but much of the discussion (or lack thereof) amongst women about sex and reproduction does have contextual grounding, as John Mullan explained.

Many young female viewers have expressed both their admiration for and solidarity with key female characters in the show, who seem to attempt to subvert the gender norms of the day and defy the restrictions placed upon them. Characters such as Eloise Bridgerton and Penelope Featherington show us that women at this time could be intellectual figures in various way. When presented with a world in which young girls do nothing expect worry about what they will wear and who they will marry, we seem to warm to these characters, simply because they do not buy into this retrogressive fantasy. And we see subversion with the pen taking physical form in Lady Whistledown, an anonymous reporter who exposes the faults and scandals of this society's most prolific members. Many have suggested that Lady Whistledown resembles the cruel side of social media: being ultra-critical and exaggerating or fabricating a story when there simply isn't one. Here we find something in the period that echoes strongly of the current moment.

Drawing their thought-provoking and insightful discussion to its close, John and Stella gave their opinions on why Bridgerton is such a hit. For John, it is the careful balance of half dutiful obedience to history and half anachronistic delight in areas such as costume, music and interiors. For Stella, it is the show's confident and effective blend of the 19th-century and the modern: Bridgerton is anchored in some aspects of the period in order for it to float free in others. A 'mixture of fastidiousness and carelessness' (in the words of John Mullan), the show is rooted in the days of regal high society, with so much that rings true to viewers in 2021. It seems that this dichotomy is what draws people back to the show, and why many of us are waiting in high anticipation of the next series.

Close

Close