Student Journalist Emilie Yang interviews UCL History of Art's Dr Aparna Kumar

27 July 2022

As part of our commitment to Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, we have appointed three student journalists to create compelling content which links Art History and EDI. In this article, student Emilie Yang speaks to Dr Aparna Kumar.

Emilie Yang [EY]: In June, I interviewed Dr. Aparna Kumar, Lecturer in the History of Art Department specialising in the Global South. In this Staff Journeys Interview, she describes how her interests in History of Art developed from her undergraduate to doctoral years. Furthermore, Dr. Kumar gives us a taste of her upcoming book on the Lahore Museum, and shares the importance of Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) to her.

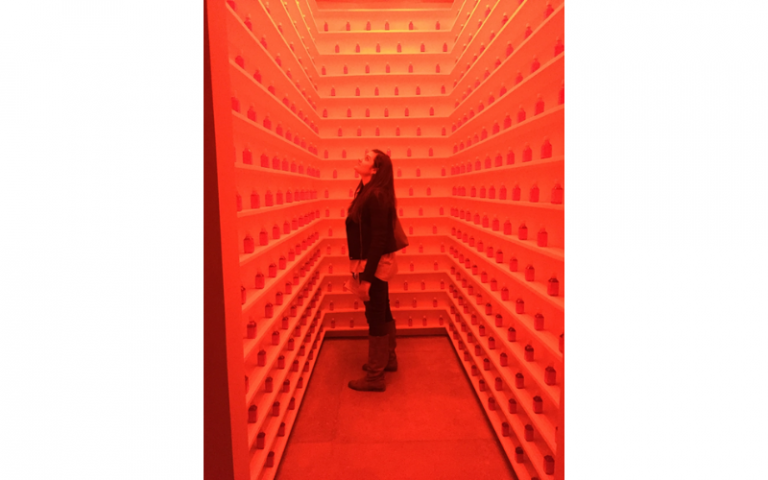

A visit to the Lahore Museum, Pakistan, 2014. All images courtesy of Dr. Aparna Kumar.

EY: When did your interest in Art begin?

Dr. Aparna Kumar (AK): As a child, I remember going to museums with my mom. It was very formative, but I have always been an extremely visual person, in a sense that I have always found visual culture very stimulating whether that’s art in museums or figures on the television. I started to think about art as a field in high school. I spent a summer in Paris where I took my first Art History course, with inspiring visits to the Louvre, the Musée d’Orsay and the Gustave Moreau museum. I would probably give my mom and Paris equal credit for my initial interest in History of Art.

EY: Why did you decide to study History of Art?

AK: I have to be very honest, I did not always want to be an art historian. I entered university as an International Relations major. My dad is from India and my mom is from the United States. From an early age, I became very interested in the diplomatic politics between the US and South Asia. I went to university with every intention of working in government.

My path changed in college when I began studying Hindi and Urdu. This language training revealed new aspects of South Asian history and politics, as well as the aesthetic dimensions of this field which I enjoyed. These studies coincided with my electives in Art History as an undergraduate. At this time, Dr Mallica Kumbera Landrus, now Keeper of Eastern Art at the Ashmolean, was a visiting professor at my university (Brown) and was offering courses in South Asian art history. Before taking her courses, I had no idea that you could be an art historian who specialised in South Asian art and culture. This class was life-changing for me because it showed me that there was a field of South Asian history that encompassed politics, diplomacy, international relations, visual culture and languages.

EY: Could you tell us a little more about your personal biography?

AK: I was born and raised in the United States. My father is an Indian immigrant who moved to the US for graduate school and my mom is white American who grew up in the Midwest. I come from a biracial, bicultural background which constantly saw me trying to find my place among different cultural conditions and conversations in my hometown and in my travels between the US and South Asia. I think my interest in South Asia as a researcher certainly has a personal dimension. My research in many ways is rooted in my trying to understand how I belong to the various identities that I occupy, categories like “Indian” and “Hindu,” but also “American” and “biracial.” My research on partition history, decolonisation, territorial and identitarian division in South Asia during the 20th century brings this inquiry into the historical and asks what role visual culture plays in mediating these categories of identity and forms of belonging. Perhaps my engagement with South Asian art also grows from the discomfort that I may have felt coming to terms with and really learning to love and accept my biracial identity and upbringing. Over the years, I have found Art History to be a really powerful way to think through these complexities.

EY: What were your undergraduate years like?

AK: I received my BA from Brown University where I double majored in International Relations and History of Art and Architecture. I had a wonderful experience at Brown; it was such an open academic and social community that allowed me to explore and find what I was interested in, then gave me the agency and the tools to craft my education. Brown is known for their open curriculum and for allowing students to find ways to fuse their diverse interests together, which is what allowed me to bring International Relations and History of Art into conversation.

My undergraduate years were so formative for my language learning. I worked with a wonderful Hindi-Urdu professor at Brown, Dr. Ashok Koul. In many ways, language led me to South Asian art history. These languages do not just provide a way to communicate; they contain aesthetic worlds in themselves that shape politics, community, and visual culture and open up new ways of thinking about the partition. At Brown, I also met several mentors, including Dr. Mallica Kumbera Landrus and Professor Vazira Fazila‐Yacoobali Zamindar, a prominent scholar of partition history. At the time, I don’t think I realised how formative my undergraduate years were, or how my conversations with these scholars would shape my academic journey.

EY: What are the differences between the British and American education systems?

AK: There are major differences- and as a lecturer who is still very new to the UK environment, I am still learning about what these differences are. I think that the main difference, especially on the PhD level, is the amount of time that you are afforded to develop your projects. The UK system is very quick. Students have three years to write their doctoral dissertation and complete their archival research. Whereas in the US, the expectation is that you take 6 years for a PhD in Humanities. There is more time built in often for students to take coursework with PhD mentors.

EY: What were your postgraduate MA and PhD years like?

AK: After I graduated from Brown in 2010, I moved straight into an MA/PhD programme. I joined the Art History department at UCLA, where I studied with Professor Saloni Mathur, a specialist in modern and contemporary South Asian art. UCLA is known for its open, progressive and interdisciplinary scholarship and for its historic engagement with the ‘non-west.’ It was an incredible environment for me to pursue my work. I got to think about modern South Asian art while taking classes in fields like Japanese art, colonial Latin American art, and African-American art, which was very generative. It also was a programme that had two specialists in South Asian art history. My minor advisor, Professor Robert Brown, specialises in early South Asian art. Having had the opportunity to work with not one but two South Asian specialists engaged in very different temporalities and geographic imaginations has undoubtedly shaped my own approach to research and teaching.

It took nine years to finish both the MA and PhD. It was quite a long process. Looking back, I appreciated the time because it gave me the space to refine my diverse research interests and to find my research project.

I came to my current book project through my MA work. When I was looking for an MA project, my supervisor Professor Saloni Mathur, who knew of my interest in diplomacy, politics and histories of partition, introduced me to the artwork of the late-Zarina Hashmi, an Indian-born, NY-based artist known for her works on paper. As a printmaker, Zarina often meditates on questions of home and displacement in her work, having lived through the partition. I became interested in her cartographic prints, especially those focused on the Indo-Pakistani border, which opened up an amazing field of creative energy around partition history and raised a number of questions around how the visual arts might help us write and understand this painful history. My work on Zarina was so energising it snowballed into my wider doctoral work on partition and museums.

I think that this privilege of time also allowed me to pursue the depth of fieldwork that my project demanded, namely to spend time in multiple locations for extended lengths of time. I spent three months in London, five months in Lahore, and eighteen months in India researching for my project.

Presenting new research on artists Zarina Hashmi and Shahzia Sikander, Jesus College, Cambridge, 2022.

A visit to the Lahore Museum, Pakistan, 2014.

EY: Can you tell us about your research and your upcoming projects?

AK: Broadly, my expertise is in modern and contemporary South Asian art and museum studies. I am interested in 20th century partition history and thinking with postcolonial theory. My research and teaching often explore the role that art and art institutions play in the development of national identities and politics in postcolonial societies like South Asia.

I am currently working on my first book project which is an extension and revision of my doctoral thesis, “Partition and the Historiography of Art in South Asia.” It is a study of the 1947 partition of the Indian subcontinent, a process of decolonization and division that marked the dissolution of the British Empire in South Asia and the arrival of India and Pakistan as nation states. These are territories that were further fragmented in the twentieth century, spanning modern-day India, Pakistan and Bangladesh today.

I am really interested in thinking about how these processes of decolonisation and division have impacted visual culture in South Asia. My book project provides a new history of the Lahore Museum in Pakistan. This was an institution that was gravely affected by the decision to partition the region in the mid-20th century because its collections of art and archaeology were also divided between India and Pakistan. The project details this division process and highlights the relationship between the Lahore Museum in Pakistan and the Chandigarh Museum in India, which now share a base collection of objects courtesy of the partition.

The project has several aims. It is at its core a history of a museum. My narrative positions museums as agents of decolonisation with ramifications for ongoing conversations around repatriation today. It also considers the museum as a fragmented material archive. Part of what my project argues is that the material archive is an essential vantage point from which to understand the partition’s social, political, economic, and epistemological ramifications.

My research is also trying to develop a method of writing for art historians that responds to the challenges of partition and its fragmentation. In this sense, the book not only traces the life story of the Lahore Museum and its objects through the partition, but asks how we might write a cross-border history of art.

With Shilpa Gupta’s Blame (2002-04), installation shot from the cross-border exhibition The Night Between Dawn, Gujral Foundation, Delhi, 2016.

EY: What are the most difficult aspects of your research? And how do you manage your time as a researcher?

AK: I think the most challenging aspect of my project was finding my research archive. Finding and putting together the story of the division of the Lahore Museum was not easy, as there was very little cohesive documentary trace of the division process. It required me to travel and live in different places for long periods of time; it required me to track the movement of different kinds of objects and to find out who the people and the voices that were involved in the division process. It was a challenge and an adventure to work from this place of archival absence and to imagine how I could reconstruct this archive and this story.

A personal challenge of my doctoral research was that it required me to move, to pick up my life and move to places that I had never lived before. The only reason why I was able to carry out the work I did is because I had an incredible network of support from family, friends and colleagues in South Asia. That practical move was also a difficult life decision to have to make. Research, especially the dissertation project, can be isolating too because you are on a personal journey with your materials, your project, and your thinking. However the gift of time spent with family was perhaps the best gift that this whole process has given me.

It has been quite the transition to my new role here at UCL. I made the move from Los Angeles during the pandemic and I am definitely still learning how to manage my research time, alongside my other teaching and admin responsibilities. Teaching has been my main focus in the last two years, something that I have been really happy to throw myself into. I learn immensely from each one of my modules and always find my in-class conversations with students to inspire new directions in my research too. Now that I am more settled in the department and in London, I am trying to find a balance and devote time to my research projects, namely finishing my book. Research management, like anything, just takes a little practice. I am looking forward to this summer because I have some writing goals that I am really looking forward to realising.

EY: Why did you decide to move to the UK, and how did you find the transition from the American to British education system?

AK: London has always been such an important city for research. It has always been a place of unexpected connection so I was very excited to relocate to a place where I think I can really thrive as a researcher and a teacher. I am very excited to have the opportunity to be in conversation with the art world here which is a very important space for South Asian artists. Having the chance to teach at an institution like UCL is also a dream come true. I entered as part of the cluster-hire focused on Arts and Visual Culture of the Global South, along with my colleagues Dr. Jacopo Gnisci and Dr. Ramon Amaro. We were hired at a time when our department was thinking about the different ways we could diversify our research culture, research community and pedagogy. It was such an exciting opportunity for me- I read the job description and I said this is me, they are looking for me!

In conversation with artist Shahzia Sikander and Dr. Vivek Gupta at Pilar Corrias Gallery, London, 2021.

EY: Does London facilitate your research in different ways to the United States because of the history between Britain and South Asia?

AK: London definitely facilitates my research in different ways from the US. London has incredible collections of South Asian art and archaeology, more than most cities outside of South Asia. But more than this, the active role that many of these institutions played in processes of colonisation and decolonisation in South Asia is an extremely important archive for me to have access to as a researcher but also as a teacher. I am very excited about bringing my pedagogical practice here, and having the opportunity to bring my students into these archival and museum spaces and to think critically in them, in ways that I would not have been able to do in the US.

Another reason why I love London is because of the number of artists from South Asia and the South Asian diaspora who are engaging with the contemporary art world here. I have had a number of friends exhibit in London in the short time that I’ve been here. It is exciting to feel like you are a part of a really energetic community and conversation.

I think that teaching histories of British colonialism in South Asia and histories of decolonisation in South Asia through questions of visual culture certainly takes on a different kind of resonance when I teach it in London. It has everything to do with the fact that we are still at the centre of the Empire. The way that people conceive of empire and the legacies of colonialism is very contingent. The kinds of conversations that we can and should be having in this place, or maybe are not having because of the place is really interesting to think about too and brings new relevance to what I am doing as an art historian. It has helped me to reconceive the stakes of my pedagogy and my research in a different way and I am really grateful for that opportunity.

Leading a tour of the British Museum on Repatriation with the UCL History of Art and Diplomacy Societies, London, 2022.

EY: What is the significance of being the only scholar teaching a discipline, museum studies, in the Department?

AK: I am excited to bring this expertise to the department. But, I wouldn’t say I am the only faculty member in our department working on questions related to museums and museum studies. Many of my colleagues here at UCL are thinking about museums in really exciting ways. It has been wonderful to connect with their research in the last two years and make connections across our approaches to museums as institutional spaces, archival spaces, and spaces for collecting and display.

I think that museums are such an interesting vantage point to think from. Museums are often seen as stagnant places that are responding to the socio-political demands that are being placed on them. But the archival materiality of collections, the histories of collecting and display that comprise these institutional spaces can bring them alive in different ways that can be useful for us as art historians. I am very interested in thinking about their relationship to colonial epistemologies, colonial forms of display and collecting, and the ways that museums remain entangled with those processes. I am also very interested in thinking about the kinds of demands that museums and exhibitions place on art historians as writers- how to write about an exhibition or how to write about spatial and curatorial juxtaposition or how to read museums, galleries and their displays as material evidence.

EY: What do you enjoy most about UCL?

AK: Working with our department’s students has been so energising! What is different about UCL from any institution that I have taught at before is that our students apply to UCL to do Art History. This is very different from the US and I think that it brings a different level of commitment to the degree programme, which our students bring to the classroom. I also have to say my colleagues are amazing and they make it a joy as well.

EY: What is the importance of EDI to you?

AK: As someone who is biracial and bicultural, I have struggled with a sense of identity and belonging my whole life, which has now carried into my career and my research questions in interesting ways. A lot of my teaching and research involves questions of equity, diversity and representation. In my modules, we talk a lot about Islamophobia, the rise of fundamentalist politics in South Asia, forms of colonial oppression and the systems of representation that enabled them, in the hope that we can use the research and pedagogical spaces that our department fosters to challenge these systems and bring about new world imaginations and new social solutions that will prioritise equality, diversity and inclusion. I think it is very important for us to be thinking about questions of EDI so that someone like me can embrace the complexities of their identity with joy and not discomfort.

Close

Close