Christina Quarles and Corporeal Paint

26 July 2022

As part of our commitment to Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, we have appointed three student journalists to create compelling content which links Art History and EDI. In this article, student Joseph Knoeppel discusses the work of artist Christina Quarles.

In April 2022, two dozen MA History of Art students joined Briony Fer and Stephanie Schwartz in Venice. As we attempted the impossible task of digesting the entirety of the 59th Venice Biennale across two days, we frequently revisited notions of legibility and sovereignty in our discussions. The Giardini and the Arsenale have been transformed into a matriarchal utopia by curator Cecilia Alemani after a three-year hiatus; around 90 per cent of the 213 exhibited artists are women. While the so-called gender imbalance was widely scrutinised in the media by journalists and gallerists alike, what struck me was the stimulating corporeal narrative weaved across the curated elements of the Biennale. How should the body be translated through art? Who should be translating which bodies? How is the female body imagined and portrayed? In this regard, the curator succeeded in capturing my attention.

For me, the work of one artist embodied the curatorial aims wholly – having admired and followed her work for several years now, perhaps I am biased. In the Giardini Pavilion, six works can be found by the queer, mixed-race woman, Christina Quarles. These descriptive words, categories, as it were, are the exact issue which the artist tackles in her work. In reading interviews with Quarles, it would seem her experience with racial identity, specifically being born to a white mother and black father and being mislabelled as white by both groups, remains central to the compositions which she produces.

Where language lacks, Quarles picks up her paintbrush. Her work explores the ambiguity and legibility of bodies which do not fit the prescribed ideals society affixes them to. The artist always begins a composition with gestural marks, punctuating the plain canvas, creating spaces and forms in which she begins to imagine figures. After stepping back to inspect her brushstrokes, Quarles begins to abstract these preliminary lines, growing and mutating imaginary bodies with every movement. When confronted with several canvases, one is immediately struck by their scale and the abundance of negative space that remains in a finished painting. The figures, unlike the large canvases that vary in their dimensions, remain a uniform size. Quarles’ own bodily limitations – the length of her arms, her height – dictate the size of the figures she draws from abstracted lines. Figures crouch, stretch, and tangle, as the artist works on raw canvas. Each is completed in a short period of time. Quarles enjoys the immediacy and contingency involved in each composition. There is little to no concealment between brushstrokes and these imperfections might be imagined as mirroring the body’s flaws.

As aforementioned, the language Quarles has developed in her paintings is based on experiences of identity; she often speaks about feelings of displacement because of her racial identity: “I was interested in using my own biography, as somebody that is born to a white mother and a black father and who is often mis-seen as white, especially by white people.” Combining lived experience with studies in critical race theory – Quarles completed a bachelor’s in philosophy before beginning her MFA – the artist’s practice contemplates how to describe the body in paint. These questions, how to represent the female or queer body, are echoed throughout the Biennale.

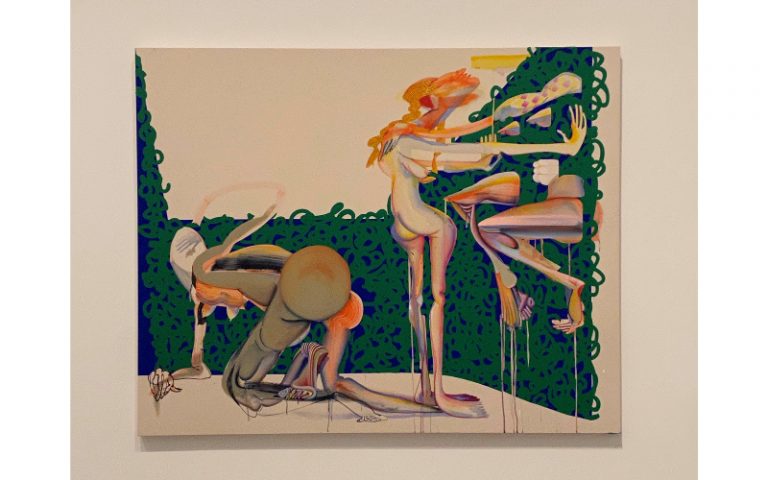

One of Christina Quarles’ paintings from the 59th Venice Biennale. Author’s photograph.

Biography aside, the works combine figuration with abstraction, throwing the interior space of the painting into chaos. Quarles disrupts traditional notions of background and foreground; there exists no formal hierarchy between the figure and the space with which it interacts. In one of the six acrylic paintings included in the Venice Biennale, three entangled figures push and morph into one another. Some limbs appear solid, and others transparent, as they move between two spatial planes. On the left, a dark green quadrilateral stretches backwards to meet another in deep blue, forming a horizon of sorts. This plane acts like a gateway, or window, into a distinctive structural space; a three-dimensional space seems to exist in the painted plane before it becomes flattened on the right-hand side of the canvas.

It is often difficult to visualise where one body begins and where another ends. Far from being limited in who receives the work, the fragmented bodies, caught in metamorphoses, present the spectator with a challenge; the body parts become pieces of a puzzle which cannot be solved. Exaggerated hands and feet often jump out from the canvas surface first. Quarles speaks about these body parts as representing an internalised sense of self; we cannot know exactly what we look like, but we can know our hands and our feet. When it comes to painting and recognising limbs in these compositions, Quarles attempts to paint the “feeling of an arm rather than the actual look of an arm.” In this sense, intimacy, and touch, on which the artist fixes importance, become key to grasping her work.

Combining a complete rejection of formal and spatial orders, her painterly experiments mix multiple artistic techniques on each canvas. Quarles uses contour line drawings, gradations, thick impasto paint, thin washes of paint, and stencils, as well as using her own body to perform gestural and abstracted brushstrokes. The balance between representational and abstract figures the artist strikes in her work obscures attributes one might use to categorise a body. Age, race, and gender are concealed in morphing figures which, like the artist’s experience with her own body, reject simple categorisation.

Quarles speaks about the pressures of having to “compartmentalise, fracture, and fragment yourself” to present to others in a certain manner. These fixed identities can have both positive and negative effects: in some instances, identities are used to marginalise a group, while in others, they are used to create a sense of community, or to mobilise struggle for political change. The bodies in a Quarles painting are often contained by a patterned plane, but the forms themselves remain open. Are we looking at the female body? Do we see age, race, or sexuality? In Quarles’ words, her paintings are about “identity and the body, and the expectations of living within a body and within a form.”

‘Casually Cruel’ (2018) by Christina Quarles at Tate Modern. Author’s photograph.

Based in Los Angeles, Quarles’ work began to draw attention in 2016. Since then, her work has featured in numerous group and solo shows internationally; some readers may have seen her solo show at the Hepworth Wakefield or South London Gallery. She is now gaining international recognition, not just her presence in the 59th Venice Biennale but her inclusion in some of the world’s leading public collections.

For those in London, I encourage you to visit her painting in the permanent collection at Tate Modern, acquired in 2019. A UCL alumnus and former senior curator of international art for Tate Modern, Mark Godfrey, wrote on the artist for the occasion of her first monograph with the Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago in 2020. (I suspect this UCL alumnus might have been instrumental in the acquisition of Casually Cruel.)

Quarles takes back her bodily sovereignty and encourages others who come across her paintings to do the same. Her works prompt discussions of legibility; how are we to look at the body when the body loses its identifiable differences? Perhaps these are questions art history will never be able to answer fully, but the works of Christina Quarles are undoubtedly a contentious visual reference for any discussions of art and identity.

Written by Joseph Knoeppel

Sources:

- Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, Christina Quarles, online video recording, YouTube, 20 May 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=mUAk2kTrgEw

- South London Gallery, Christina Quarles: Studio Visit, online video recording, YouTube, 10 June 2021, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MVmZy6XtnDk

- Quarles, Christina, Grace Deveney, Uri McMillan, and Mark Godfrey, Christina Quarles (Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago, 2020)

Close

Close