In 1957, the great prehistorian Vere Gordon Childe wrote an article which was published under the title "Valediction". In it he set out what he regarded as the main tasks confronting archaeology. The fulfilment of these - including the establishment of a reliable chronology and an understanding of ancient ecology - would, in his view, place archaeology on a par with other more established disciplines.

For a decade Childe had been Director of the Institute of Archaeology in London. He declared that with its broad geographical range and ground-breaking work in archaeological sciences, the Institute was singularly suited to the development of the new archaeology that he envisaged. In October of that year, back in his native Australia, he jumped to his death in the Blue Mountains.

The Institute that Childe loved and led is celebrating its 75th anniversary. From scrappy beginnings sketched out on the back of an envelope, it has grown to become one of the largest archaeology departments in the world, with some of the greatest figures in world archaeology amongst its alumni. As archaeology has been transformed beyond recognition in the half century since Childe's death, the Institute continues to labour in the tasks that he charged it with.

Its 75-year history sheds light on the development and growth of archaeology in Britain and around the world.

Finding the site

If Childe is the most illustrious name associated with the Institute, Wheeler's must come a close second. Sir Mortimer Wheeler dreamt of a school to train a generation of archaeologists in fieldwork techniques and more. The Institute was his brainchild, but the task of turning the dream into a reality fell largely to his wife Tessa Verney Wheeler. Her organisational and financial acumen brought the project to fruition, though she died a little more than a year before the grand opening.

By the mid 1920s the world of British archaeology was starting to expand, with student numbers and paid posts both growing healthily. Wheeler identified a need for specialised, systematic training in archaeological skills such as excavation, drawing and photography, and in 1926 he began to conceive a detailed scheme for a university-based establishment. When he was installed as keeper of the London Museum the same year, his pocket, he wrote, "bulged with the blueprint of that Institute of Archaeology which was the next obvious step in the development of our infant but growing science".

The Wheelers marshalled support at the University of London. The fundraising drive was boosted by a £10,000 gift by a millionaire well-wisher to the Egyptologist Sir Flinders Petrie, which he passed on to Wheeler, along with his vast collection of Egyptian and Palestinian artefacts. On April 29 1937, with five members of staff and three students already enrolled, the Institute of Archaeology opened its doors.

These portals were the grand entrance to St John's Lodge, an early 19th century villa in the inner ring of Regents Park. The institute acquired the building on a 14-year lease for a very modest rent, and promptly filled the ballroom with the dusty crates of the Petrie collection. Students in these early years recall the Institute as a friendly if chaotic place with flint knapping on the veranda, Maurice "Cookie" Cookson's photography equipment scattered around, and the occasional animal escapee from the nearby London Zoo pursued by keepers with nets.

St John's Lodge had been leased by the Marquess of Bute until 1916, when it housed a hospital for injured soldiers. Today the lodge is valued at over £100m, and is owned by the Sultan of Brunei, who counts more than 100 Rolls Royce cars amongst his fleet of 3,000. Wheeler would probably have approved such high living; Childe most likely - with equal conviction - would not.

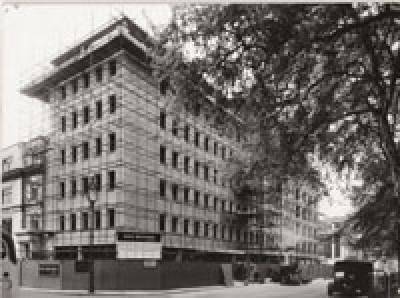

The Institute's lease on St John's Lodge expired in 1951, and a new home was mooted on the north side of Gordon Square in Bloomsbury. Four Georgian houses on the site were demolished in 1955, and construction began on the comparatively dull building that opened in 1958, and houses the Institute today. Popular myth states that it went up on a bombsite: in fact the war damage (which included a plane crash) had been repaired by the time demolition began. The Institute's environmental archaeologist Ian Cornwall conducted a site evaluation, and rather disappointingly found nothing of any note beyond a few fragments of animal bone.

Close

Close