| IS THE MIND

AHEAD OF

THE BRAIN? -- BENJAMIN LIBET'S EVIDENCE EXAMINED

by Ted Honderich What are the differences between the philosophy of consciousness and the science of it? That general question as well as the particular one about mind and brain is raised is by the neurophysiological research of Benjamin Libet et al. This reseach has lately been given a kind of attention by Daniel Dennett and Marcel Kinsbourne in The Nature of Consciousness: Philosophical Debates (1997) edited by Ned Block, Owen Flanagan and Guven Guzeldere. It has also surfaced in The Volitional Brain: Towards a Neuroscience of Free Will (1999), edited by Libet, Anthony Freeman & Keith Sutherland, and John Searle's Royal Institute of Philosophy Annual Lecture. The research finding is to the effect that a conscious event happens before the relevant brain event. Thus It is used to refute many theories that identify the two events, and also a common theory of psychoneural lawlike connection that supposes the events are simultaneous. Karl Popper and John Eccles, in The Self and Its Brain, depended on the research to argue for a certain dualistic picture, in fact a "trialistic" picture, since it includes the brain, and mental or conscious events, and something certainly distinct from them, the Self-Conscious Mind. The research, naturally enough, also helps out with determinism and freedom. It serves to save our free will or power of origination. Very useful research then -- if OK. The following paper from The Journal of Theoretical Biology, first published undered the title 'The Time of a Conscious Sensory Experience and Mind-Brain Theories', looks into the the question. It was attended to confidently by Professor Libet -- Subjective Antedating of a Sensory Experience and Mind-Brain Theories: Reply to Honderich. The reply in turn got a response -- Honderich's 'Is The Mind Ahead of the Brain -- Rejoinder to Benjamin Libet'. ----------------- Libet (1978, 1981) and Libet et al. (1979) claim to advance a single hypothesis about the time of a conscious sensory experience in relation to the time when there occurs a certain physical condition, "neuronal adequacy" for the experience. This can be and has been taken to throw doubt on theories that identify mind with brain (Feigl, 1960; Armstrong, 1968; Davidson, 1980) and on a dualistic theory of psychophysical lawlike correlation (Honderich, 198l a,b). Popper & Eccles (1977) use the contentions of Libet et al. as evidence for a greatly different dualism, one which denies psychophysical lawlike correlation and asserts a kind of surveillance and control of the brain by "the self-conscious mind", despite some acting of the brain on "the self-conscious mind". The contentions derive in part from many previous findings (Libet, 1965, 1966, 1973; Libet et al., 1964, 1967, 1972, 1975). The aims of the present paper are first, fully to demonstrate an inconsistency involving two hypotheses, and to note a conclusion about experimental findings that follows from this; second, to raise a considerable doubt about the preferable hypothesis; third, to show why it has been supposed that the hypothesis is evidence against an identity theory of mind and brain and the theory of psychophysical lawlike correlation, and evidence for "the self-conscious mind"; fourth, to show why the hypothesis, if true, provides no evidence in either case, and fifth, to show that a different hypothesis, which if tenable would provide the evidence, is wholly untenable. What is maintained by the authors derives from two sets of findings (1.1 to 1.3 and 2.1 to 2.4 below) pertaining to neuronal activity and to the temporal order of a subject’s pairs of sensory experiences, and also from (3) findings having to do with a "primary" evoked potential in somatosensory cortex. Very roughly, findings 1.1 to 1.3 are to the effect that there is a certain delay in sensory experience, but finding 2.1 apparently conflicts with this. Finding 3, with the help of 2.2 to 2.4, is used to give an explanation of the apparent conflict. (1.1) Experiments on human subjects, with their agreement, and in conjunction with surgical treatment, are said to show that after trains of stimulation are applied directly by inserted electrodes to postcentral cortex there is a considerable delay, up to about 0.5 sec after the beginning of the train, before cortical activity reaches "neuronal adequacy" for eliciting a conscious sensory experience. What is said to be delayed, to repeat, is precisely the physical condition of "neuronal adequacy", as distinct from the experience itself, whatever is to be said of its time. (1.2) There is said to be a very similar delay with direct subcortical stimulation trains. (1.3) There is also said to be a very similar delay with single pulses of peripheral stimulation, say a single pulse to the skin of the hand. (2.1) If a single-pulse stimulus to skin at just above threshold level is applied after (say 0.2 or 0.3 sec) the beginning of a stimulus train direct to somatosensory cortex, it would be expected that subjects would report that conscious experience for the skin stimulus began after conscious experience for the cortical stimulus. This would be expected on the basis of 1.1 and 1.3. Reports of tests, however, were predominantly of experience for the skin stimulus beginning before experience for the cortical stimulus. (2.2) There is no such surprising order of conscious experiences reported with subcortical stimulation. If a skin stimulus is applied after the beginning of a subcortical stimulus train, subjects report that sensory experience owed to the skin stimulus began after sensory experience owed to the subcortical stimulation. (2.3) Similarly, if the beginning of subcortical stimulation is simultaneous with a skin stimulus, subjects report simultaneous sensory experiences. (2.4) Similarly again, if a skin stimulus is applied before the beginning of subcortical stimulation, subjects report that experience of the skin stimulus came before experience owed to the subcortical stimulation. (3) Peripheral stimuli and subcortical stimuli quickly elicit a relatively localized "primary" evoked potential in somatosensory cortex, owed importantly to the specific (lemniscal) projection system. The onset of this potential, the arrival of a fast projection volley, is only about 15 msec after a stimulus to the hand. However, a stimulus train applied direct to somatosensory cortex does not elicit a similar type of response. The first set of findings (1.1 to 1.3) are to the effect that "neuronal adequacy" for any sensory experience is achieved only after a certain delay. Finding 2.1, which is crucial, appears to conflict with this. That is, the ordering by subjects of their experiences (experience-owed-to-skin-stimulus before experience-owed-to-cortical-stimulation) suggests that the experience of the peripheral stimulus occurs considerably sooner than about 0.5 sec later. There is thus a contrast with cortical stimulation. However, there is no such contrast evident with subcortical stimulation, as indicated by 2.2, 2.3 and 2.4. The two sets of findings, together with (3) the finding of a "primary" evoked potential, are said to issue in an hypothesis about the timing of conscious sensory experiences owed to peripheral and subcortical stimulation, and also an explanation of what is postulated in the hypothesis. The explanation of what is postulated in the hypothesis has to do in part with the specific (lemniscal) projection system and the "primary" evoked potential. Some statements made by the authors are of one hypothesis, or suggest it. Other statements are of, or suggest, a different hypothesis. It will be necessary, partly for fairness, to quote extensively. Unless otherwise indicated, all page references in what follows are to Libet et al. (1979). The following statements are somehow to the effect that an experience occurs at a certain time but is "antedated" to the time of certain earlier events, the "primary" evoked potential. [a] "[The hypothesis] postulates (a) the existence of a subjective referral of the timing for a sensory experience, and (b) a role for the specific (lemniscal) projection system in mediating such a subjective referral of timing." (p. 193) [b] "(1) Some neuronal process associated with the early or primary evoked response, of SI (somatosensory) cortex to a skin stimulus, is postulated to serve as a ‘time-marker’. (2) There is an automatic subjective referral of the conscious experience backwards in time to this time-marker, after the delayed neuronal adequacy at cerebral levels has been achieved (see Fig. 2). The sensory experience would be ‘antedated’ from the actual delayed time at which the neuronal state became adequate to elicit it; and the experience would appear subjectively to occur with no significant delay from the arrival of the fast projection volley." (pp. 20 1-2. Cf. Libet, 1978, p. 75) [c] "The results obtained in these experiments provide specific support for our present proposal, that is, for the existence of a subjective temporal referral of a sensory experience by which the subjective timing is retroactively antedated to the time of the primary cortical response (elicited by the lemniscal input)." (p. 217) [d] "The specific projection system is already regarded as the provider of localized cerebral signals that function in fine spatial discrimination, including the subjective referral of sensory experience in space. Our present hypothesis expands the role for this system to include a function in the temporal dimension. The same cortical responses to specific fast projection inputs would also provide timing signals. They would subserve subjective referral in such a way as to help ‘correct’ the subjective timing (relative to the sensory stimulus), in spite of actual substantial delays in the time to achieve neuronal adequacy for the 'production’ of the conscious sensory experience." (pp. 220-1) [e] "… for a peripheral sensory input, (a) the primary evoked response of sensory cortex to the specific projection (lemniscal) input is associated with a process that can serve as a ‘time-marker’; and (b) after delayed neuronal adequacy is achieved, there is a subjective referral of the sensory experience backwards in time so as to coincide with this initial ‘time-marker’." (p. 222) These statements are certainly not all clear, but their burden is the following hypothesis. Such a conscious experience as that of a skin stimulus occurs only when "neuronal adequacy" is achieved, but it is somehow "antedated" of "referred" to an earlier time. That is, despite what is said of the experience’s involving "subjective referral backwards in time", the experience itself occurs only about 0.5 sec after the beginning of stimulation. The experience does not occur at the time to which it is "referred". We can call this the "delay-and-antedating" hypothesis. It is also what is conveyed by the authors, as will be worth noting, in one of their diagrams and several other passages. ---------------------------------------------------------------

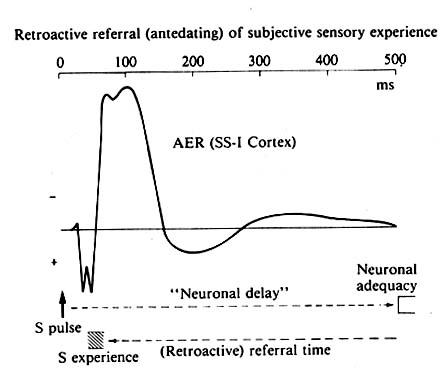

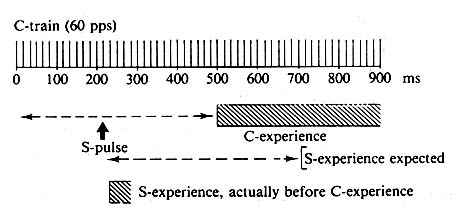

-------------------------------------------------------------- [f] Their Fig. 2 (p. 201), reproduced here as Fig. 1, has to do in the main with the "primary" evoked potential. It is said of the figure in part: "Diagram representing the ‘average evoked response’ (AER) recordable on the surface of human primary somatosensory cortex (SI) in relation to the.., hypothesis on timing of the sensory experience. Below the AER, the first line shows the approximate delay in achieving the state of ‘neuronal adequacy’ that appears (on the basis of other evidence) to be necessary for eliciting the sensory experience. The second line shows the postulated retroactive referral of the subjective timing of the experience, from the time of neuronal adequacy’ backwards to some time associated with the primary surface-positive component of the evoked potential." (p.201) Presumably "neuronal adequacy" is not taken as necessary for eliciting what has already happened, earlier in time. The experience, at the later time, is merely "referred" to the earlier. (g) It is stated (p. 221) that the hypothesis in question "deals with the problem of a substantial neuronal time delay apparently required for the ‘encoding’ of a conscious sensory experience, by introducing the concept of a subjective referral of sensory experience in the temporal dimension." [h] Finally, there is what is said of a quite different idea, owed to Donald MacKay, and more particularly of an amendment of it. MacKay’s idea "accepts our proposal that there is substantial delay in achieving neuronal adequacy with all inputs, peripheral or central; but it would argue that, in those cases where there is apparent antedating of the subjective timings of the sensory experience, the subjective referral backwards in time may be due to an illusory judgement made by the subject when he reports the timings… For example, it could be argued that during the recall process, cerebral mechanisms might ‘read back’ via some memory device to the primary evoked response and now construe the timing of the experience to have occurred earlier than it in fact did occur." (pp. 219-20) An amendment of this idea is contemplated, one that is said in fact to turn it into the hypothesis of Libet et al. "…if any ‘read back’ to the primary timing signal does occur, it would seem simpler to assume that this takes place at the time when neuronal adequacy for the experience is first achieved, when the ‘memory’ of the timing signal would be fresher; such a process would then produce the retroactive subjective referral we have postulated." (p. 220) The burden of all that has been reported here so far, then, is that such a conscious experience as that of a skin stimulus occurs only at the time when "neuronal adequacy" has been achieved, about 0.5 sec after the beginning of stimulation, despite what is said of "antedating". (I) On the other hand the

authors’ Fig.

1 (p. 199), reproduced here as Fig. 2, pertaining to the crucial

finding

2.1, about subjects’ surprising ordering of experiences, could hardly

be

clearer in its quite different import.

FIG. 2. Figure I from Libel et al. (1979) p. 199. Reproduced with permission. --------------------------------------------------------------- The S-experience (experience of a skin stimulus) is specified as "actually before C-experience" (experience owed to cortical stimulation). It is shown as occurring only a few msec after the stimulus-pulse (S-pulse). In the note to the diagram it is said: "If S were followed by a... delay of 500 msec of cortical activity before neuronal adequacy’ is achieved, initiation of S-experience might.., have been expected to be delayed until 700 msec of C [stimulus train to somatosensory cortex] had elapsed. In fact, S-experience was reported to appear subjectively before C-experience..." The note, although perhaps less definite in its intention, thus accords with the diagram. (II) What the crucial finding 2.1 established, it is said and implied, is that conscious experience of certain stimulation did not occur at the time of "neuronal adequacy". "If the subjective experience were to occur at the same time as the achievement of neuronal adequacy in the case of either stimulus, one would expect the subject to report that the conscious sensory experience for the C stimulus began before that for the threshold S pulse (Fig. 1) ….However, the pooled reports were predominantly those of sensory experience for the C (cortical) stimulus beginning after, not before, that for a delayed threshold S pulse.. (pp. 199-200) (III) It is stated, of the crucial finding 2.1, that "the subjective experience of the skin stimulus occurs relatively quickly after the delivery of the S pulse, rather than after the expected delay of up to about 500 msec for development of neuronal adequacy following the S input." (p. 200) That is, the skin-stimulus experience itself occurs earlier, rather than after the expected delay. (IV) It is flatly stated that "subjective experience of a peripherally-induced sensation is found to appear without the substantial delay found for the experience of a cortically induced sensation." (p. 222) (V) Very importantly, it is noted that findings 1.1, 1.2 and 1.3 above, about delay in achieving "neuronal adequacy", are not to be taken in a natural way, as asserting or implying that the experiences in question are subject to the given delay. That is left open. "The two timings, for subjective experience vs. neuronal adequacy, might not necessarily be identical." (p. 200) (Cf. Libet, 1978, p. 75) (VI) It is stated that the hypothesis in question introduces "an asynchrony or discrepancy between the timing of a subjective experience and the time when the state of ‘neuronal adequacy’ associated with the experience is achieved." (p. 221) (VII) It is stated that there is "a dissociation between the timings of the corresponding ‘mental’ and ‘physical’ events." (p. 222) The burden of these statements (I to VII), although some phrases might be taken as ambiguous, is that a conscious experience occurs earlier rather than later, i.e. before about 0.5 sec after the beginning of stimulation rather than about 0.5 sec after the beginning of stimulation. We can call this the "no-delay hypothesis". As remarked, Eccles uses the hypothesis of Libet et al., whatever it is, to argue for the existence of "the self-conscious mind". Eccles states the hypothesis a number of times. Compare (i) and (ii) with (iii) and (iv). (i) "The experiments of Libet on the human brain.., show that direct stimulation of the somaesthetic cortex results in a conscious sensory experience after a delay as long as 0.5 sec ... although there is this delay in experiencing the peripheral stimulus, it is actually judged to be much earlier, at about the time of cortical arrival of the afferent input.... This antedating process does not seem to be explicable by any neurophysiological process. Presumably it is a strategy that has been learnt by the self-conscious mind.., the antedating of the sensory experience is attributable to the ability of the self-conscious mind to make slight temporal adjustments, i.e. to play tricks with time..." (Popper & Eccles, 1977, p. 364) (ii) "...Libet developed a most interesting hypothesis, namely that, though a weak single (SS) just threshold single skin stimulus requires up to 0.5 sec of cortical activity before it can be experienced, in the experiencing process it is antedated by being referred in time to the initial evoked response of the cortex (Popper & Eccles, 1977, p. 259) (iii) "The ... experimental design tested the supposition that a just-threshold single skin stimulus (SS) was effective in producing a conscious sensation after the same incubation period. . . as a just-threshold train of cortical stimulation (CS), which is as long as 0.5 sec. If that were so, when the SS was applied during the minimal CS train, the SS should be experienced after the CS; but it was usually experienced before!" (Popper & Eccles, 1977, p. 257) (iv) "There can be a temporal discrepancy between neural events and the experiences of the self-conscious mind." (Popper & Eccles, 1977, p. 362) Passages i and ii are to the effect that the experience is later (i.e. about 0.5 sec after the beginning of stimulation) and is somehow antedated. Passages iii and iv say otherwise: the experience is earlier (i.e. not nearly so much as about 0.5 sec after the beginning of stimulation). There is the same inconsistency suggested by two parts of a diagram (Popper & Eccles, 1977, Fig. E2-3, p. 258) reproduced here as Fig. 3. -----------------------------------------------------------------------

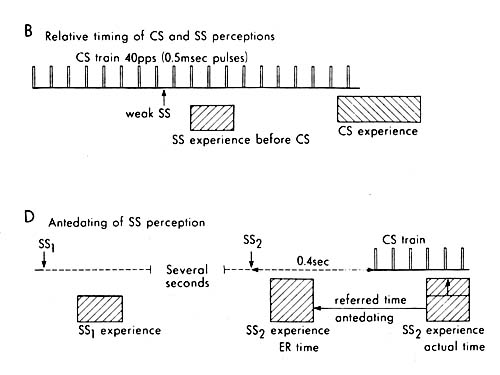

In part D, which has to do with tests whose details are not all relevant to the present point, a just-threshold single skin stimulus (SS2) is shown as giving rise to an experience whose "actual time" is about 0.6 sec later. There is "antedating", somehow involving "ER [evoked response] time", which is not further explained. However, in part B of the diagram, which pertains to the crucial finding (2.1) above, the SS experience is shown as actually occurring earlier rather than later. (CS is cortical stimulation.) The diagram specifies "SS experience before CS [experience]". The inconsistency in the work of Libet et al. and Eccles, and in other reports of the work of Libet et al. (Cotman & McGaugh, 1980, pp. 806-7), is worth noting for itself. Not both the hypothesis that there is delay in experience but "antedating", the "delay-and-antedating hypothesis", and the hypothesis that there is no such delay, the "no-delay hypothesis", can be true. That conclusion carries corollaries, of course. One is that if the delay-and-antedating hypothesis is true, then if there are putative findings which entail the no-delay hypothesis, those findings are false. The like corollary has to do with taking the no-delay hypothesis to be true. Any putative findings which entail the delay-and-antedating hypothesis are then false. It is not within my competence, however, to examine these findings in detail, notably the crucial finding 2.1. If the inconsistency itself and

hence the

fact that there are two hypotheses in question are important, partly

for

a further conclusion of mine, it can confidently be said that it is the

delay-and-antedating hypothesis to which the authors, at bottom, are

committed.

It is the preferable hypothesis. In my view, the authors’ failure to

notice,

despite their commitment, that there are two inconsistent hypotheses in

question has had an effect on their understanding of the consequences

of

the delay-and-antedating hypothesis, consequences for the mind-brain

issue.

It is my suggestion that failing to notice the inconsistency, and hence

that there are two hypotheses on hand, has been significant in enabling

Libet et al. and Eccles and Popper (Popper & Eccles, 1977,

pp.

531, 565), to come to certain conclusions about the mind-brain identity

theory, the dualistic theory of psychophysical lawlike correlation, and

"the self-conscious mind". 2. Is The "Delay-and-Antedating Hypothesis" Acceptable? To consider another matter first, however, how are we to understand the preferable hypothesis? It is in part that an experience is somehow "antedated" or "retroactively antedated" or "referred back" to a "time-marker". What does that come to? Very little account of the supposed phenomenon itself, as distinct from what is supposed to explain it, is given. The central idea appears to be that a subject has a conscious sensory experience including or involving or accompanied by the belief or impression that it is not then happening. He may have a conscious sensory experience, reportable as "sensation in right hand", which conscious sensory experience occurs about 0.5 sec after stimulation, and after another sensory experience. His experience of the right-hand sensation includes or involves or is accompanied by the belief or impression that the sensation occurred significantly earlier than about 0.5 sec after stimulation, before the other sensory experience. There seem to be very great difficulties in this idea - which, it must be remembered, is crucially different from Mackay’s simpler idea. It is true, surely, that the actual having of any conscious sensory experience includes or involves or is accompanied by the belief or impression that the experience is present. That is, it is happening now. Further, it might be said that there is the belief or impression that the experience is after another experience, immediately prior in time. The having of any experience, that is, somehow brings in a belief or impression as to a temporal property (presentness) and perhaps also a temporal relation (after another experience) (Honderich, 1977). But then the supposed phenomenon of a conscious sensory experience we have been considering, the phenomenon of "antedating" or "referring back’’ , involves imputing something very like certain self-contradictory beliefs to subjects. It involves, more precisely, imputing something like simultaneously-held, fully explicit self-contradictory beliefs to subjects, as distinct from the common sort of self-contradiction where the conflicting beliefs are not brought together. The supposed phenomenon, by way of a kind of summary description, is the phenomenon of a conscious experience which a subject might describe in the words "present-sensation past" or "now-sensation then", or perhaps "later-sensation earlier". Libet et al. say that the processes in referral or antedating are to be regarded as "unconscious and ‘automatic’ in nature and… not distinguishable by the subject" (p. 220). What processes are there in question is not entirely clear. However, we cannot choose to regard a conscious sensory experience as something of which the subject is unaware. It seems, to repeat, that a conception of presentness and perhaps of a temporal relation enters into the having of any sensation. Are there really certain experiences such that the involved belief or impression as to presentness is, so to speak, simultaneously denied? On the assumption that a belief or impression of a temporal relation enters into the having of any sensation, can it be that there are certain experiences such that the belief or impression is simultaneously denied? As illustrated above in [d], it is said that the supposed "antedating" phenomenon is related to something else also owed to the specific (lemniscal) projection system. "…the concept of subjective referral in the spatial dimension, and the discrepancy between subjective and neuronal spatial configurations, has long been recognized and accepted; that is, the spatial form of a subject sensory experience need not be identical with the spatial pattern of the activated cerebral neuronal system that gives rise to this experience." (p. 221) "The newly proposed functional role for the specific projection system would be additional to its known role in spatial referral and discrimination." (p. 222) In fact, however, there is no relevant analogy whatever between "temporal referral", of the kind with which we have been concerned, and the given discrepancy between (a) spatial experience and (b) neuronal spatial configurations. The latter discrepancy obviously involves no kind of self-contradictory experience, the simultaneous occurrence of contradictory beliefs or impressions. Libet remarks that hypotheses are

the weaker

for involving ad hoc assumptions (Libet, 1978, p. 74). It is

also

said that hypotheses are the weaker for involving "added assumptions"

(p.

220). It is my own second and tentative conclusion here that the

delay-and-antedating

hypothesis is open to objection along these lines. However, it is not

within

my competence to judge the findings which are put in question, or whose

interpretation is put in question, if the delay-and-antedating

hypothesis

is rejected. 3. Explanation of Mind-Brain Conclusions To turn now to mind-brain theories, it is said (Libet, 1978, p. 80) that "on the face of it, an apparent lack of synchrony between the ‘mental’ and the ‘physical’ would appear to provide an experimentally-based argument against ‘identity theory’, as the latter is formulated by Feigl, Popper, etc." However, it is allowed that a certain reply to the argument is possible. The reply is not specified. It is then said that "a temporal dissociation between the mental and the physical events would further strain the concept of psychophysiological parallelism or, if one prefers, of co-occurrence of corresponding mental and neuronal states. It could thus have an impact on the philosophical interpretation of such parallelism or co-occurrence when formulating alternative theories of the mind-brain relationship." In the later (1979) article it is said, differently, that "dissociation between timings of the corresponding ‘mental’ and ‘physical’ events" raises serious but not insurmountable difficulties for identity theories, but that the dissociation does not contradict "the theory of psychophysical parallelism or correspondence" (pp. 221-2). The seeming change of mind about dualistic theories is not explained. In a still later article it is said that "the temporal discrepancy creates relative difficulties for identity theory, but.. . these are not insurmountable" (1981, p. 196). It is said, further, that the data are "compatible with the theory of ‘mental’ and ‘physical’ correspondence" (1981, p. 182), and that the data do "introduce a novel experimentally-based feature into our views of psychophysiological correspondence, with some interesting philosophical implications that merit analysis" (1981, p. 183). Further, it is said, without explanation: "What we are discussing is not any denial of correspondence between mental and physical events, but rather the way in which the correspondence is actually manifested" (1981, p. 195). I am uncertain what to make of what is said, so vaguely, of psychophysical "correspondence". Can such "correspondence" hold between events at different times? Does such "correspondence" require only such a loose connection between the brain and the "self-conscious mind" as posited by Eccles and Popper? It is clear how the findings as to the timing of conscious experiences may be taken to threaten an identity theory, or the theory of psychophysical lawlike connection, or parallelist theories. Evidently a conscious occurrent or process or experience cannot be identical with a physical event or process if the mental and physical items have different temporal locations or durations. Consider the claim that a conscious experience was identical with the physical process which constituted "neuronal adequacy" for it. The claim must be false if the experience and the processes occurred at different times. Again, the theory of psychophysical lawlike correlation naturally takes the correlated mental and physical items to be simultaneous. That is part of the theory. Evidently, if the studies of Libet et al. did establish of certain mental and physical items that they were not simultaneous, this would indeed raise a difficulty for the given theory of psychophysical lawlike correlation. The same is true, evidently, of a parallelist theory denying psychophysical lawlike correlation but involving psychophysical simultaneity, the parallelism taken as simply inexplicable or somehow owed to ongoing divine intervention. It is a theory, perhaps, which has no contemporary defenders. Finally, if there were mental events separate in time from their physical bases, that might be taken as going some way towards supporting the theory of the self-conscious mind. Given what seems to me the obscurity of that theory, I shall not attempt to say more about why that might be true. Eccles’ remark in passage (i) above carries the idea that something plays tricks with time, which thing is the self-conscious mind. (There, admittedly, he is to be taken as speaking of the "trick" of "antedating".) It is clear, to sum up, that the findings as to the timings of conscious experiences may be taken to have these various consequences if the findings are taken as issuing in the no-delay hypothesis. That is one fact, about which I shall say a word more in a moment. Another fact, to repeat, is that clearly it is the delay-and-antedating hypothesis that is favoured by the authors, despite their inconsistency. It is my conjecture that the authors, not having clearly distinguished the two quite different hypotheses about timing, have supposed that the studies in question have somehow established the no-delay hypothesis, to the effect that certain mental and physical items are not simultaneous. That, fundamentally, is why they draw their conclusions about the mind-brain relation. However, they must choose one or the other of the two hypotheses, and the one they favour, the delay-and-antedating hypothesis, is not at all to the effect that certain mental and physical items lack simultaneity. The experience of the skin

stimulus, on

the delay-and-antedating hypothesis, is simultaneous with the physical

process which is taken to constitute "neuronal adequacy" for it. The

experience

may indeed be of a strange self-contradictory kind. This in itself, so

long as psychophysical simultaneity is preserved, is no problem

whatever

for either an identity theory, or the theory of psychophysical lawlike

correlation, or a theory of psychophysical parallelism. Nor, evidently,

is a problem raised by the fact that the experience in one part somehow

has reference to an earlier time. That in itself no more makes the

experience

non-simultaneous with its "neuronally adequate" physical process than

does

the very different referring feature of an ordinary memory or recall

experience

make that experience non-simultaneous with its "neuronally adequate"

physical

process-or time-distortion in an hallucination make that experience

non-simultaneous

with the related physical process. 5. Failure of "No-Delay Hypothesis" It may be supposed, I have said, thatboth an identity theory and the theory of psychophysical lawlike correlation would be affected by the no-delay hypothesis, the hypothesis to which the authors do not incline, but which appears to have influenced their thinking. Still, that is not all that is to be said of the hypothesis. It would not only put two things at different times, thereby threatening certain mind-brain theories. The no-delay hypothesis is as follows: "neuronal adequacy" for a certain experience is achieved only about 0.5 sec after the beginning of stimulation, but the experience occurs before then. What is "neuronal adequacy"’? It appears to be a kind of neuronal condition which is a sufficient condition for the emergence of the experience. There are certain quite general philosophical problems here (Honderich, 1982, p. 311f) but it must appear that the no-delay hypothesis is in fact false because self-contradictory: it asserts that something cannot occur before a certain time - before a sufficient condition occurs - and that it does. It is true, as remarked above, that if the studies of Libet et al. did establish of certain mental and physical items that they were not simultaneous, this would raise a difficulty for, say, the theory of psychophysical lawlike correlation. Still, it must be false that a mental item occurs before the physical item on whose later existence it depends. In fact, in my view, identity

theories

are open to a conclusive objection of a philosophical kind (Honderich,

1981a, pp. 294-8; 1981b, pp. 430-4) while the dualist theory of

psychophysical

lawlike correlation is open to no such objection, and is increasingly

confirmed

by neuroscience. The theory of the self-conscious mind, in my view,

faces

insurmountable objections of philosophical and neuroscientific kinds.

These

propositions, about the three mind-brain theories, cannot be defended

here. BACK Professor Libet

made a reply, in

the next

issue of The Journal of Theoretical Biology. My rejoinder to

his

reply is ''Is the Mind Ahead of the Brain --

Rejoinder

to Benjamin Libet'. Armstrong, D. M. (1968). A Materialist Theory of The Mind. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. Cotman, C. W. & Micaigjh, J. L. (1980). Behavioural Neuroscience. New York: Academic Press. Davidson, D. (1980). Essays on Actions and Events. Oxford: Clarendon. Efiol, H. (1960). In: Dimensions of Mind (Hook, S. ed.) pp. 24-34. New York: New York University Press. Honderich, T. (1977. In: Time and the Philosophies (Ricoeur, P. ed.) pp. 141-154. Paris: UNESCO. Honderich, T. (1981a). Inquiry 24, 277. Honderich, 1. (1981b). Inquiry 24, 419. Honderich, T. (1982). Philosophy 57, 291. Libet, B. (1965). Perspectives Biol. Med. 9, 77. Libet, B. (1966). In: Brain and Conscious Experience (Eccies, J. C. ed.) pp. 165-81. New York: Springer-Verlag. Libet, B. (1973). In: Handbook of Sensors’ Physiology (Iggo, A. ed.) Vol. 2, pp. 743-790. Heidelberg: Springer-Verlag. Libet, B. (1978). In: Cerebral Correlates of Conscious Experience (Buser, P. & Rougeul-Buser, A. eds) pp. 69-82. Amsterdam: Elsevier, (1981). Phil. Sci. 48, 182. Libet, B., Alberts, W. W., Wright, E. W., Delattre, L. D., Levin, G. & Feinstein, B. (l964). J. Neurophysiol. 27, 546. Libet, B., Alberts, W. W., Wright, F. W. & Feinstein, B. (1967). Science 158, 1597. Libet, B., Alberts, W. W., Wright, E. W. & Feinstein, B. (1972). In: Neurophysiolagy Studied in Man (Somjen, G. G. ed.) pp. 156-168. Amsterdam: Excerpta Medica. Libet, B., Alberts, W. W., Wright, E. W., Lewis, M. & Feinstein, B. (l975). In: The Somatosensary System (Kornhuber, H. H. ed.) pp. 291-308. Stuttgart: Georg Thieme. Libet, B., Wright, E. W., Feinstein, B. & Pearl, D. K. (1979). Brain 102, 193. Popper, K. R. &

Eccles, J. C.

(1977). The Self and Its Brain. Berlin: Springer.

Originally published as 'The Time of a Conscious Sensory Experience and Mind-Brain Theories', Journal of Theoretical Biology (1984) 110, pp. 115-129 For my view of some philosophy that has something to do with Libet's work, see Mind the Guff -- An Examination of John Searle's Thinking on Consciousness and Freedom. |