The terracotta warriors and the 'portrait' debate

5 December 2014

In the last few days, we have noticed fresh interest in our work in both conventional and social media.

We are very pleased

that our research keeps engaging the broader public - and also sorry if the

lines that follow sound slightly killjoy!

We are very pleased

that our research keeps engaging the broader public - and also sorry if the

lines that follow sound slightly killjoy!

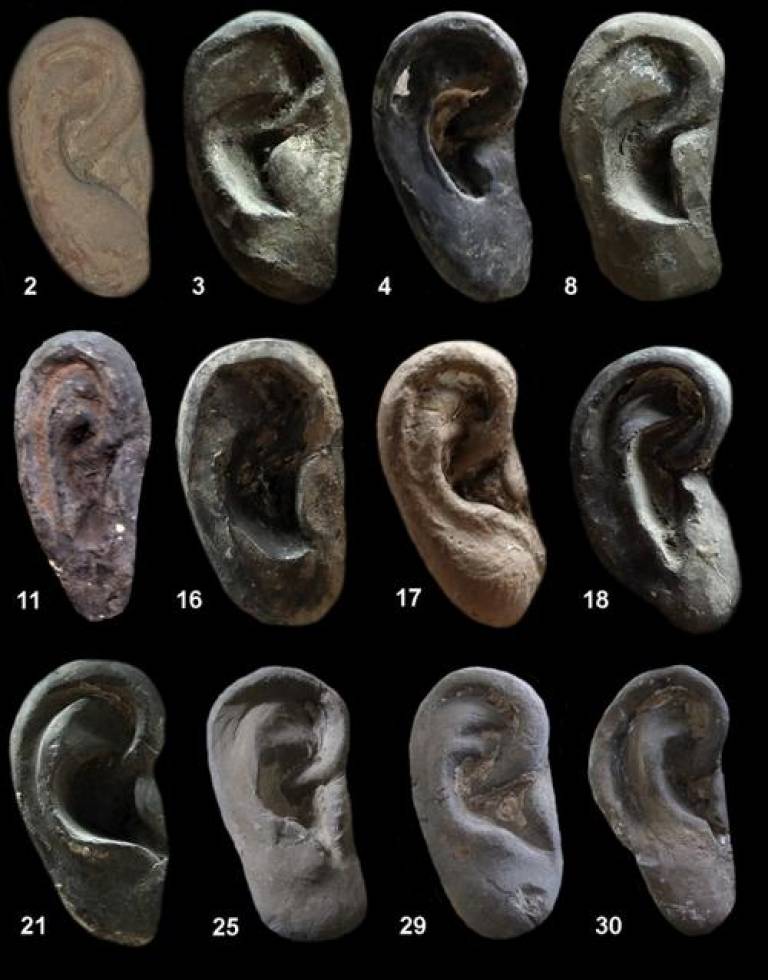

3D models of twelve of the warrior ears used for the initial comparison.

The recent wave of attention, news reports and re-tweets was probably triggered by a combination of factors. On the one hand, PBS has just broadcast in the US a documentary film based on several highlights of the project. This film is broadly similar to, although not the same as, "New Secrets of the Terracotta Warriors", which aired in the UK and other countries late last year and went on to win the British Archaeology Award to the Best Presentation of Archaeology to the Public. On the other hand, an article appeared in National Geographic that also focused on some aspects of our research. By sheer chance, both just happened to be publicised during the same week. Also by chance, the bulk of the team was working in Xi'an while this was happening (an extremely enjoyable research trip yielding very interesting results - but that's another story!) so we were initially unaware of the relatively big response the media reports generated, which now spans from Chile and the US through the UK to Turkey, to name a few.

The strand of our research that has attracted particular attention most recently is the comparative study of some warriors' ears. The study was published in the Journal of Archaeological Science a few months ago and back then it received quite a lot of news coverage, including a detailed commentary in Nature. In a previous blog we explained the innovative approach to the use of digital 3D models for geometric morphometric comparisons and highlighted some of its potential. As noted there and, importantly, as the academic paper explained, this study was primarily a "proof of concept", demonstrating that it was possible to reconstruct accurate 3D models of the warriors based on digital photographs, and then to systematically and statistically compare the morphology of different warriors or warrior parts (or any other objects, for that matter - hence the great potential of this approach!).

We started with the ears because a) they are relatively easy to photograph for 3D modelling, b) they have been used in art history before to discriminate between artists, c) in real humans, they are as individual as our fingerprints. In addition, ears presented an interesting starting point because multivariate analysis of ear and head shapes should help us clarify how whole heads were constructed. These sorts of questions are nicely encapsulated in the recurrent reference to Mr Potato Head.

Now to the outcome of the initial study. Our main result so far - and it's a very important one - is that the method seems to work. This is the big highlight of the JAS paper. In order to demonstrate this, we used a set of 30 ears as a case study. Geomorphometric analysis indicated that none of the ears in this sample was identical to the next, and as such provided an enticing glimpse of the anatomical variability among the warriors. In this respect, our work builds on some excellent long-term work by Chinese researchers on this topic, including a book-length treatment of the warrior styles by the Terracotta Army Museum's former Director Yuan Zhongyi. The idea that the warriors, despite being partly made from pottery moulds (and also partly hand-carved), might be inspired by real individual subjects is understandably an exciting further possibility we should not discount.

There is still, however, a big leap from ours current 3D findings (or indeed from any previous work) to a confident claim that all the warriors are portraits of actual individuals - as implied in some of the media coverage, perhaps because of the inevitable simplification that comes with tight word-counts and deadlines. If the warriors were accurate portraits, all the ears could be expected to be different - but the same claim cannot be made in reverse. First, we still need to systematically study other features of their bodies and see the extent to which they reveal the use of a set number of moulds and the application of individual traits - or, most likely, a combination of both. Second, we cannot make any definitive claims about the individualism of the figures based on 30 ears when the warriors bear around 15,000 of them! For those interested in the fine detail of this work, the academic paper is actually rather short and publicly available.

Previous studies by Chinese and western scholars have provided strong evidence that moulds were used at least for the basic shaping of some warrior parts such as heads or hands, even if these were subsequently modified (for example with specific hairstyles or headgears), to create an impression of individualism. The use of moulds makes it rather unlikely that whole warriors are faithful portraits of entire real people - even if the figure makers clearly strived for realism, and the tantalising possibility remains that they may sometimes have had real subject in mind as they finished off their life-sized works.

As our project moves forward and we expand our sample (to other ears

but also other body parts), we are hoping to, building on the previous research, employ

these innovative methods to deconstruct this

combination of moulding and individualisation more systematically.

Crossing this information with that from the makers' stamps and inscriptions on

some of figures, and studying their spatial distribution, we may be able to

infer the number of production units involved, their interplay, and how the

ceramic warriors were combined with weapons as they were transferred to the

pit. We still have a lot of Imperial Logistics to disentangle. Please keep

watching this space!

Marcos Martinón-Torres is Professor of Archaeological Science at the UCL Institute of Archaeology and the Director of the Imperial Logistics Project.

Andrew Bevan is a Professor at the UCL Institute of Archaeology and is the Deputy Director of the Imperial Logistics Project.

Xiuzhen Janice Li is a Senior Archaeologist at the Emperor Qin Shihuang's Mausoleum Site Museum, China.

Close

Close