Sargon's Nineveh letters

With about 1,200 letters surviving in the original, the correspondence of Sargon II of Assyria (721-705 BC) uncovered in the royal archives of Nineveh has firmly secured its place among the most fascinating letter collections preserved from antiquity. The texts are an invaluable source for the reconstruction of the history and culture of Assyria, Babylonia, Urartu and most other regions of the Middle East in the late 8th century BC.

Muddled context

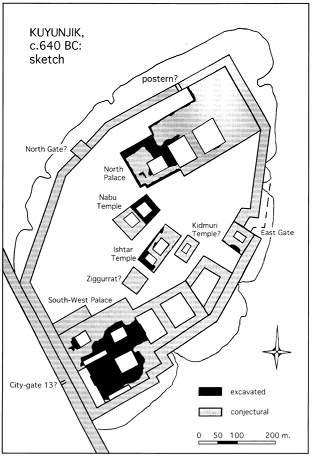

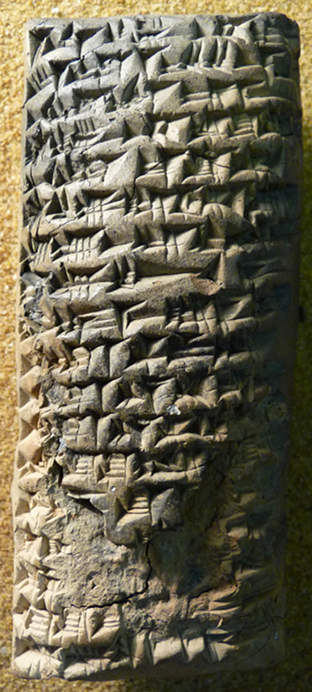

The main mound of Nineveh is today known as Kuyunjik. It marks the site of the royal palaces and administrative headquarters of Sargon's son Sennacherib (704-681 BC) and his successors. In the 19th century, Kuyunjik came to the attention of the first archaeologists to explore the region. After some early work by Paul-Emile Botta, Austen Henry Layard excavated there in the 1840s and early 1850s, followed by Hormuzd Rassam, W. K. Loftus, George Smith and others. They found around 30,000 cuneiform tablets and fragments, among them the royal correspondence of Sargon II and some of his successors. Today, all these tablets are in the British Museum where, since 2009, work is underway to digitie them all and make them accessible online [http://cdli.ucla.edu/collections/bm/bm.html].

The archaeological methods of the 19th century were rough compared to the standards of our time, and the exact whereabouts and circumstances of the tablet finds of Kuyunjik are generally unknown. Modern researchers therefore face the challenge not only of identifying tablet fragments that belong together (a process called "joining") but also of reconstructing the original archives and, as far as this is possible, the principles of their organisation.

Most of the c. 1,200 letters of the correspondence of Sargon II were found in Nineveh. Some can be shown to originate from the South-West Palace (SAA 1 31, SAA 1 33, SAA 5 64, SAA 5 91, SAA 15 24, SAA 15 184, SAA 15 199, SAA 17 22), found during Layard's excavations in rooms 40-41, and most probably all of Sargon's letters were stored together in this part of the South-West Palace. But although Sargon's correspondence represents more than half of all known letters from the Neo-Assyrian period, it is very likely that more of this king's correspondence still remains to be discovered, in Nineveh and elsewhere.

Identifying Sargon's letters

The royal archives of Nineveh contain letters from the reigns of Sargon II to Assurbanipal (668-c.630 BC), his great-grandson. However, the letters are not dated and do not normally mention the king's name. Only some Babylonian letters very helpfully address Sargon by name. Assigning the many other missives from Nineveh, including the hundreds of fragments, to the reigns of specific kings has therefore presented an enormous challenge for modern scholarship. Our current understanding of these sub-archives rests mainly on the painstaking work of Simo Parpola.

A key tool in identifying other letters from Sargon's reign are the names of his correspondents who, as high officials, often served as year eponyms TT and whose names and titles are therefore recorded in the Assyrian Eponym Lists and Eponym Chronicles. These texts allow the attribution of the letters sent by these officials to the reigns of Sargon or other kings. Connections of these letters with others in regard to content permit further identification, as do links with information contained in the royal inscriptions. Place names and personal names are especially important in this respect.

Most of Sargon's Nineveh letters which can be dated are from the later years of his reign, whereas the first five years of his rule are hardly represented at all; the extant texts from that period were found at Kalhu. But while we can be reasonably certain in separating the letters of Esarhaddon (680-669 BC) and Assurbanipal among the Nineveh material from those of Sargon, it is very difficult to distinguish with certainty the letters dating to the last years of Sargon's reign from those of his successor Sennacherib, who retained many of his father's officials in their posts. Until quite recently, it had generally been assumed that no letters whatsoever were known from the reign of Sennacherib. This picture changed significantly when Manfried Dietrich was able to date some 65 letters in the Babylonian language to the early years of Sennacherib's rule. Still, this is a very modest number of texts and, moreover, none of the Assyrian letters can confidently be attributed to Sennacherib's correspondence. Are his letters still waiting for their discovery?

Why are Sargon's letters in Nineveh?

How is it that these letters were found in Nineveh when Sargon's political and administrative centres were Kalhu and, after 706 BC, Dur-Šarruken? Nineveh was indeed not the original destination of the letters. Most of them were sent to Kalhu and only later transferred to Nineveh, either directly or, perhaps more likely, via Dur-Šarruken where Sargon and his officials would have wanted to consult them after the court and central administration had been moved there. In the end, however, while some letters remained in Kalhu, most reached Nineveh. The arguably simplest explanation is that Sargon's successor Sennacherib was responsible for this, moving his father's state correspondence once he chose Nineveh to be the new centre of the Assyrian Empire.

There are, however, alternative scenarios: Simo Parpola has assumed that the letters were already being kept in Nineveh during Sargon's lifetime because his crown prince Sennacherib resided there and shouldered much of his father's administrative responsibilities when he was away on his frequent military campaigns. However, only one extant letter (SAA 1 153) is addressed to crown prince Sennacherib while he in turn is the author of several missives addressed to the king (SAA 1 27, SAA 1 28, SAA 1 29-40, SAA 5 281). On the other hand, Sargon had temporarily resided in Nineveh sometime during the years 707 and 706 BC before he could move to his new city and the palace of Dur-Šarruken, and one might argue that the letters were moved from Kalhu to Nineveh for this occasion and never stored in Dur-Šarruken at all. But Sargon had also spent the years 710-707 BC in Babylon, and from the letters themselves it is clear that this did not cause that city to serve as the administrative hub of the empire. Even more importantly, two letters from Sargon's correspondence were excavated in Dur-Šarruken (SAA 5 81; SAA 5 100), proving that at least some of the letters were kept there at one point. That Sennacherib had his father's correspondence moved to Nineveh and the South-West Palace when he became king of Assyria remains, therefore, the most satisfying scenario.

Contents and senders

It was vital for the running of the Assyrian Empire that the communication between centre and provinces worked quickly and efficiently. Moreover, Sargon was almost constantly on the move, taking a very active role in military campaigns. Like the so-called Nimrud Letters, the royal correspondences of Tiglath-pileser III (744-727 BC) and Sargon unearthed in Kalhu, Sargon's Nineveh letters deal with affairs not only inside the Assyrian Empire but in the entire Middle East. The letters concerning the neighbouring states are typically intelligence reports, informing Sargon about troop movements and the whereabouts of his key political enemies, especially Rusa of Urartu and Marduk-apla-iddina (Merodach-Baladan II), his rival for the Babylonian throne.

The Nineveh material contains letters sent by Sargon himself, surviving either in the form of archival copies or perhaps drafts, by the crown prince Sennacherib and the highest administrative and military officials in the Assyrian Empire. The best attested correspondents are the governors serving in provinces across the empire; sometimes we even have letter dossiers from successive governors of a given province. However, the geographical distribution of the known Sargon letters is very uneven and not all regions of the empire are represented: there is, for example, a considerable gap in regard to materials from the western provinces whence only a very few letters survive. The bulk of these letters may still be awaiting their discovery.

Early on in his reign, Sargon II decided to move his capital from Kalhu (modern Nimrud) to Dur-Šarruken (modern Khorsabad), and the planning and construction of the new centre for the empire is one of the main themes of the letters. Otherwise, the letters tend to deal with similar administrative, political and military topics as the Nimrud Letters. The royal correspondence of the 8th century BC is therefore markedly different from the 7th century letters of Esarhaddon and Assurbanipal, the majority of which concerns cultic and scholarly topics.

Further reading:

Dietrich, 'The Babylonian Correspondence of Sargon and Sennacherib', 2003.

Fuchs and Parpola, 'The Correspondence of Sargon II, Part III', 2001.

Lanfranchi and Parpola, 'The Correspondence of Sargon II, Part II', 1990.

Millard, 'The Eponyms of the Assyrian Empire 910-612 BC', 1994.

Parpola, 'The Correspondence of Sargon II, Part I', 1987.

Reade, 'Ninive (Nineveh)', 1998-2001.

R. F. Harper published hundreds of Sargon's letters in his Assyrian and Babylonian Letters belonging to the Kouyunjik Collection of the British Museum, volumes I-XIV (Chicago 1892-1914). His work remains useful, although his "copies" (i.e. drawings of clay tablets that reproduce their cuneiform signs) no longer satisfy modern discipline standards. 1979 saw the publication of many additional texts and fragments in Simo Parpola's Neo-Assyrian Letters from the Kuyunjik Collection = Cuneiform Texts from Babylonian Tablets in the British Museum, part 53 (CT 53) and Manfried Dietrich's Neo-Babylonian Letters from the Kuyunjik Collection = Cuneiform Texts from Babylonian Tablets in the British Museum, part 54 (CT 54).

Content last modified: 5 Nov 2012.

Mikko Luukko & Karen Radner

Mikko Luukko & Karen Radner, 'Sargon's Nineveh letters', Assyrian empire builders, University College London, 2012 [http://www.ucl.ac.uk/sargon/essentials/archives/sargonsninevehletters/]