|

|

|

HENGE TO HOUSE - POSTCIRCLES IN A NEOLITHIC AND BRONZE AGE LANDSCAPE AT KING'S DYKE WEST, WHITTLESEY, CAMBRIDGESHIRE South-cast of the Flag Fen basin, near a small land bridge that once

joined the fen islands of Whittlesey and Northey, recent excavations

have encountered an intricate pattern of later prehistoric monuments

and settlement. The work, which has led to the unexpected discovery

of a henge, round barrows, and areas of Bronze Age settlement (Fig.

1), was undertaken by the Cambridge Archaeological Unit over the winter

of 1999/2000 on behalf of Hanson Brick Ltd in advance of clay extraction.

Representing a microcosm of the surrounding larger landscape, the site

at Whittlesey presents an opportunity to look at relationships between

monuments as focal places and contemporary occupation during the later

Neolithic and Bronze Age. Materially the site was rich, enabling a resolution

of detail that only large, landscape-scale open-area investigations

permit. |

|

| Outside the south-east entrance of the henge was the larger of the two barrows (28 m in diameter). Penannular in plan, its entrance or causeway was also oriented to the south-east. At the barrow's centre was a deep grave cut containing a single inhumation in the remains of a 'log' coffin, and buried alongside the individual was a small polished flint knife. A small ring of posts encircled the grave and next to this was a single cremation burial. The southern circumference of the barrow also contained two later Bronze Age cremation deposits. The second, smaller barrow (15 m in diameter) shared the same penannular plan, but this time oriented towards the east. Less elaborate than its counterpart, it was distinguished only by a central burial. Situated between the two barrows was a small 'satellite' cremation cemetery containing both Food Vessel and Collared Urn. | |

| North-east of the henge and barrows were traces of Early Bronze Age settlement. Pits and post-holes, including at least one circular structure 4 m in diameter, contained impressive Collared Urn assemblages, including some heat-distorted sherds which could be wasters. The assemblage was similar to that from the upper fill of the henge ditch. | |

| Late Bronze Age settlement occupied the same area, characterised this time by simple post-built round-houses with south-cast oriented porches. Amongst these, however, stood a substantial east facing structure defined by an external circuit of posts, and a wall line marked by a continuous post-ring (Fig. 2). The interior was marked by post settings and a group of 'storage' pits. Inside the southern half of the house, following the curve of the wall line, was a large rectangular pit which contained recurring dark layers of fragmented post-Deverel-Rimbury pottery and butchered lamb bones, interleaved between thin spreads of clean clay. If the lamb bones are seen as representing a pattern of seasonal slaughter then perhaps such a repetitive act of deposition served to mark the annual cycle for the duration of the house. | |

|

In a Fenland landscape recognised for its field systems the absence of contemporary boundaries on our site raises interesting questions. Extensive Bronze Age enclosure has been recorded immediately to the north and yet our settlement remained unenclosed. Could it belie different histories of land enclosure and settlement? Elsewhere Bronze Age settlement is superimposed on field systems but here the monuments may have provided a focal point for occupation events, drawing people back to this place. The transformation of space and its occupation (in this case from henge to house) came about via a subtle stratigraphy of inhabitation, tethering people and place. Mark

Knight

|

|

|

EXCAVATIONS AT MEMBURY, EAST DEVON In 1986, Mrs Nan

Pearce, a member of the Devon Archaeological Society, recognised sherds

of Neolithic pottery on the surface of a recently ploughed field near

the village of Membury, 8 km north of Axminster in east Devon. Because

a find of this nature suggested that ploughing had cut through a previously

undisturbed Neolithic context, a trench measuring 2.5 x 2 m was excavated

shortly afterwards. This revealed part of a circular feature that could

either have been a ditch terminal or a pit, from which substantial amounts

of prehistoric pottery were recovered. When these had been conserved,

it was possible to reconstruct almost half of a Hembury ware bowl. Thereafter,

fieldwalking was carried out in the area revealing localised concentrations

of worked flint and several polished axe fragments as well as evidence

of apossible Romano-British building in the south-cast corner of the

field. |

|

| In August 1998

limited excavations were conducted in an attempt to finally resolve the

nature and extent of Neolithic activity at the site. Since no accurate

plans existed to record the location of the 1986 excavation, the 1998

trenches were laid out based on photographs of the earlier excavation.

As the topsoil at this location had, on previous occasions, proved extremely

difficult to excavate by hand, a mechanical excavator carried out the

initial topsoil clearance. The base of the ploughsoil was then cleaned

by hand exposing several surviving subsoil features. The excavation revealed two distinct phases of activity represented by a group of four Neolithic pits and a large stone filled feature which initially caused great excitement until it was found to be the stone lined flue channel of a Romano-British corndrier. Two, one metre sections through this feature produced 127 sherds (770 g) of pottery, roofing slate and a small assemblage of greensand chert fragments. At first these were thought to be prehistoric chert-working debris that had become residually incorporated within a Roman deposit. However, closer examination revealed several large pieces of greensand chert that had been dressed after they had been built into the lining of the corndrier producing waste flakes similar in appearance to those from prehistoric stone-working. |

|

|

The Neolithic

pits varied in size from 0.5 m to almost 2 m in diameter although they

rarely exceeded 0.25 m in depth. Each contained a variety of worked

flint and chert as well as pottery from several plain bowls, characteristic

of the South Western regional style. The most impressive group derived

from the largest pit which was made up of 304 pieces of worked flint

and chert including two leaf arrowheads and a pottery assemblage weighing

c. 1500 g. The pottery was recovered from around the edge of

the pit, while the two leaf arrowheads were found at the centre. An

initial layer of silting which formed around the pottery suggests that

the pits may have been left open for some time after artefacts were

placed within them. Martin Tingle Wymer, J.J. 1966. Excavations of the Lambourn Long Barrow, 1964. Berkshire Archaeological Journal 62, 1-16

|

|

|

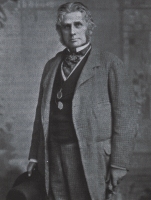

LIEUTENANT-GENERAL

A.H.L.F. PITT RIVERS

|

|

|

A scion of the minor aristocracy and squirearchy, Lieutenant-General

Augustus Henry Lane Fox Pitt Rivers became a major landowner late in

life through a series of fortuitous circumstances, namely the death

or disqualification of several intervening heirs. He was born a Lane

Fox on the family estate at Bramham, Yorkshire in 1827 and brought up

in London. In 1845 he was commissioned into the Grenadier Guards and

became a specialist in musketry instruction and the history of firearms.

He saw active service briefly in the Crimea but he owed his rapid promotion

to the purchase system, and his Postings were mainly of an administrative

nature. |

|

|

Fascinated by

the raths and promontory forts which he saw in Ireland in the early

1860s and by the hillforts and dyke systems of England, he turned his

attention to antiquarian fieldwork at, for instance, Danes' Dyke (North

Yorkshire) and Cissbury (Sussex). In the course of this work he began

to develop systematic methods of rigorous field investigation and laid

the foundations for the serious study of archaeology in Britain. He

was also active on the councils and committees of several learned societies.

|

|

| The Larmer Tree Grounds | |

| Our millennial picnic is to be held Pitt Rivers' own pleasure gardens on the Rushmore Estate. The Larmer Tree Grounds were laid out in 1880 to provide recreation for the people in the neighbouring towns and villages. The Larmer Tree itself was a wytch-elm which stood, as tradition has it, on the spot where King John used to meet with his huntsman for the Royal Hunt when he stopped at King John's House in Tollard Royal. The original tree still bore leaves as late as 1894 around which time it was replaced by an oak, planted in the centre of the decayed rim. The origin of the word 'larmer' has been the subject of some debate in the past but seems likely to mean something like a 'rush boundary' (from maere, meaning boundary and laefer being Old English for a rush). Given the position of the tree and surrounding gardens on the top of a chalk hill the presence of rushes in the immediate vicinity seems a little unlikely but the association with a boundary is very plausable as the tree stood within a few paces of the meeting-place of two counties (Wiltshire and Dorset) and three parishes. The name Rushmore was originally spelt Rushmere and maybe of similar derivation. | |

|

The General

adorned his gardens with a delightful group of follies: an open-air

'singing theatre' with a Poussin-esque landscape backdrop, a dining-hall,

the exotic Indian Rooms, a 'temple', bandstand, and reed-thatched garden

houses. Bronze statues of a mounted Ancient British hunter, Japanese

storks and a bronze horse, classical busts and urns stood along the

grassy walkways and under trees and streams cascaded down flights of

stone steps into the ornamental pool in a shady dell. Here the General

would entertain one and all with his own brass band on Sundays throughout

the summer and regularly opened the gardens for races and sports, and

other entertainments. The gardens attracted over 44,000 visitors in

1899 and were still popular for picnics and social events in the 1920s

and 30s when modest catering could be provided. Julie Gardiner

|

|

|

STOP PRESS - URGENT NEWS FOR REAL ALE FANS

|

|

|

So far, it seems, that the highlight of this year's Institute of Field Archaeologists' annual conference in Brighton was the trip to Harvey's Brewery in Lewes. Our spies tell us that something of a lock-in occurred and that a large number of people, Society members included, got a little tipsy on some very fine ale. Well guess what folks? Harveys have offered to provide us with some of their very special brew for the Millennium Picnic - you will be able to buy Best from the barrel or treat yourselves to a bottle or two of The General's Tipple - yes, you've guessed it, our very own labelled beer for a special occasion. So we'll see you all at the Larmer Tree on 19 August then?

|

|

|

EXHIBITION OF ARCHAEOLOGICAL PHOTOGRAPHS

|

|

|

Elaine Wakefield has been the full time photographer' with Wessex Archaeology for over 10 years - her photographs have appeared in PPS and PAST on South numerous occasions. The Salisbury and South Wiltshire Museum, the Close, Salisbury, is mounting a temporary exhibition of Elaine's work entitled 'Capturing Time' which opened on 3 March and runs until 3 June.

|

|

THE

REV. WILLIAM STUKELEY'S LOST MEGALITHIC AVENUE

|

|||

|

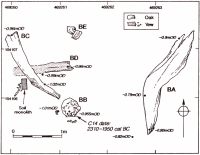

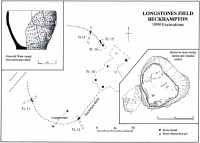

It is difficult to imagine how a megalithic avenue of least 1.5 km long, comprising over 100 stones, some as much as 4 m high, could be lost. But one was, and now, thanks to the records of a diligent antiquarian, it has been rediscovered. The monument in question is the Beckhampton Avenue, leading from the western entrance of the famous Avebury henge monument in Wiltshire. All that is visible above ground today are two substantial standing stones the Longstones - situated in a field 1.2 km to the west of Avebury. These, along with other remnants of the avenue, were first recorded by William Stukeley in 1722, but even at that point the monument was sadly dilapidated (Stukeley 1743). Since Stukeley's day the existence of the avenue has been seriously questioned, a number of scholars arguing that the Longstones formed part of a megalithic setting independent of the Avebuy complex. |

|||

|

Last summer

a team from Leicester, Newport, and Southampton excavated an area adjacent

to the Longstones. Aided by a high-resolution geophysical survey undertaken

by the Ancient Monuments Laboratory of English Heritage, a sizable area

was stripped over the course of the putative avenue. Three pairs of

features corresponding to the position of six stones were revealed,

running in a line directly towards the Longstones. The stone sockets

into which the megaliths had been set were recorded in four instances,

their spacing being identical to that of the stones of the West Kennet

Avenue leading from the southern entrance of Avebury. However, the most

visible traces of this stretch of the avenue took the form of medieval

stone burials and post-medieval destruction pits. Three stones (of local

sarsen) were found intact and neatly buried in chalk-cut pits. By analogy

with similar burials recorded during excavations in Avebury and along

the West Kennet Avenue during the 1930s (Smith 1965), the toppling and

concealment of these stones (whether for clearance or religious reasons)

probably took place in the 14th century. Though not of the immensity

of some of the Avebury stones, the three excavated blocks were still

of considerable bulk (2.5-3.0 m long). One included stone axe polishing

marks on its surface, probably made before it was incorporated in the

avenue. Another was riddled with natural perforations, into one of which

had been placed a curious assemblage comprising a split cattle long

bone and several flint flakes. Mark Gillings Joshua Pollard Dave Wheatley Smith, I.F. 1965. Windmill Hill and Avebury: excavations

by Alexander Keiller 1925-1939. Oxford: Clarendon Press

|

|||

|

Come on, you can't put it off any longer. Book now via Tessa Machling for the event of the millennium. The Millennium picnic is at the Larmer Tree Gardens, Tollard Royal, Wiltshire on Saturday 19 August 2000 from 12.00 noon to 7.00 pm. It's a full afternoon's entertainment plus lunch and cream tea. Prices are £25 per head for adults, £10 ages 4-14, under 4s free. Accommodation details are available.

|

|||

|

The following are all available from

T-shirts (one size) £8 and Sweatshirts (one size) £18 available in red, green, gold, grey and light blue (please state choice of colours in order of preference). Exclusive silver jewellery: earrings (stud or clip): £26; brooch/pendant: £28; cufflinks: £32 Enamel studs: £1.50 Ties: silk £14.95; polyester: £7.95 Cheques should be made out to the Prehistoric Society (sorry, no credit cards).

|

|||

|

THE HEART OF NEOLITHIC ORKNEY: SCOTLAND'S NEW WORLD HERITAGE SITE

|

|||

| In December 1999 The Heart of Neolithic Orkney was inscribed by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organisation (UNESCO) as a World Heritage Site. It was officially launched by the First Minister, Donald Dewar, on 24 March 2000. The First Minister and the Deputy First Minister, Jim Wallace also unveiled a plaque to mark the World Heritage Site. Patrick Ashmore of Historic Scotland took the lead in preparing the successful nomination, which was submitted in 1998. The Heart of Neolithic Orkney joins two other Scottish Sites on the List: St Kilda accepted as a natural site in 1987, and the Old and New Towns of Edinburgh, a cultural site approved in 1995. The Heart of Neolithic Orkney is therefore the first archaeological site to be honoured in this way in Scotland. | |||

|

What is The Heart of Neolithic Orkney and why is it so important?

What does World Heritage Status mean? What are the problems facing The Heart of Neolithic Orkney?

How can I find out more? · a free colour leaflet summarising the Management Plan Proposals -

send a SAE to Duncan McKendrick, Room G49 Inquiries can be directed to Dr Sally Foster who is taking the lead in finalisation of the Management Plan.

Sally Foster

|

|||

|

AN EXCITING NEW EBA DAGGER GRAVE FROM FIFE

|

|

| Things may be rough for the Grundy family these days, but for the 4000-year-old inhabitants of Rameldry Farm in Fife, life was good. On 21 February, ploughing exposed the capstone of a cist containing a crouched adult inhumation, the remains of a sheathed dagger and six V-perforated buttons. Mr Smith, the farmer, contacted Historic Scotland straight away, and through the kind offices of the Balbirnie Estates Headland Archaeology Ltd excavated immediately. The bones were not in good condition but there should be enough organic material from the cist for a C14 date. | |

|

The dagger belongs to the general family of flat riveted blades which form a distinctive component of the range of EBA metalwork following the transition to full bronze metallurgy at the end of the 3rd millennium cal BC. The blade is around 130 mm long. While further details will only emerge following conservation, the dagger has clearly had an arrangement of 5 peg rivets set symmetrically about the heel. Traces of an organic hilt plate - possibly of horn - survive and this appears to have been embellished with tiny metal pins. Owing to the extent of corrosion, their overall design remains unclear for the moment, but at least one row seems likely to have followed the semicircular outline of the hilt recess. The tongue-shaped blade retains traces of a sheath, possibly of haired skin. |

|

| The buttons, 42-51 mm in diameter, were found in the chest area. Five are of jet or a similar material, and the sixth - bronze-coloured, perhaps recalling the bronze-covered buttons of Continental Europe - may be of stone. One of the 'jet' buttons has a crudely-incised cross design on its upper surface, and a circumferential edge groove. Traces survive of a white material in the design, similar to that seen on other jet jewellery (and indeed some beakers), and thought to be polishing material for jet, left in for decorative effect. Uniquely, however, the button also has a zigzag pattern in each arm of the cross, which seems to have been achieved through differential polishing. | |

|

Although buttons are found with both male and female inhumations, in Scotland (at least) daggers appear to have been associated with males, particularly senior males (see A. Henshall, Scottish dagger graves, in J Coles & D D A Simpson, eds, Studies in Ancient Europe, Leicester, 1968, 173-95). Work by a team of specialists - on material identification and sourcing, on pollen, on the bones, etc. - will now seek to reveal more about this intriguing find. Stephen Carter, Trevor Cowie and Alison Sheridan Henshall, A. 1968. Scottish dagger graves. In J Coles & D D A Simpson (eds), Studies in Ancient Europe, 173-95. Leicester.

|

|

|

The Ninth Europa Lecture by Professor John Coles, will be delivered at the Society of Antiquaries after the AGM on Wednesday 31 May 2000 at 5.00 pm. The lecture is entitled 'Prehistory Writ Plain: wetland archaeology and the wide world' and will be followed by a wine reception.

|

|

|

|

|||

| I recently published a note on the flint axehead illustrated here (Saville 1999), which was found about five years ago near Montrose in Angus, eastern Scotland. It is a fine, but relatively small, example of a particular type of all-over-polished flint axehead, which is often of above average length, has side facets, and a symmetrical form with near-straight tapering edges and a semi-circular butt. The most distinctive attributes of the type, however, are the very high-gloss finish and the use of flint with fossil inculsions and/or of unusual colour, often variegated or marbled as here. | |||

|

There are some

twelve or so examples of these axeheads known from Scotland, mostly

from near the east coast (Sheridan 1992), and there have been occasional

reports of similar axeheads from eastern England. I am currently attempting

to collate this information and would be delighted to hear from any

museum curators or private collectors who have examples of these axeheads,

or from anyone who can direct me to any published or unpublished finds.

Please contact me at: Department of Archaeology, National Museums of

Scotland, Chambers Street, Edinburgh EHI 1JF

Saville, A. 1999. An exceptional polished flint axe-head

from Bolshan Hill, near Montrose, Angus. Tayside & Fife Archaeological

Journal 5, 1-6 Alan Saville

|

|||

|

THE

MILLENNIUM: AND HOW WE AVOIDED IT (NEARLY)

|

|

|

Leaving the snow lying across the New Forest we ventured to Cyprus

- the birthplace of Aphrodite. The car we hired seemed to be powered

by a couple of hamsters on a wheel but we were hopeful it would see

us around the island as we ventured out and about from our hotel just

north of Pafos in search of prehistoric sites. |

|

| The main museum

in Pafos is housed in a large shed, although it looks more imposing from

the outside. It does have some interesting things, though, including the

1st century pottery hot water bottles for various parts of the body. Each

is concave on the underside with the front aptly showing the part of the

limb it is to go on. There were some wonderful Neolithic stylised crosses,

mostly female, with extremely elongated necks and odd little hands. You

could say that the style and layout of the museum is very much on a 'themed'

basis: if it looks similar put it in the same case! Some true provenances

would have been helpful, as would a guide book, especially as some of

the numbers have been shifted around on the exhibits... The museum did, however, have a map of the area which lead us to the site at Lemba, just a stones throw from our hotel which, although not marked from the main road, is signposted once you are off the main road! Less than 1 km from the sea, the site is set on a slight promontory. As with the Khirokitia site some reconstruction has been done (Fig. 2) and one of the reconstructed huts was much bigger than we had seen before. The settlement was destroyed in 2500 BC with many objects left in place - some of them are in the museum in Pafos. |

|

|

One of the houses

(labelled house 2 on Fig. 2) had contained many storage vessels while

graves under the floors were linked to the living area by small holes

to allow contact between the living and the dead - the holes may have

been for liquid offerings to the ancestors. Other graves in the open

area beyond the houses were marked by depressions with capstones over

the simple pits. Usually a single child or adult was buried with a few

grave goods. Two buildings in the excavation area probably served as

kitchens as many animal bones were found. Each house was equipped with

a large central platform, and experiments have shown that these provided

heat throughout their surfaces - much as an Aga stove. Val Moore

|

|

|

The Archaeolink Prehistoric Park in Aberdeenshire, which opened in

June 1997, is a centre for the interpretation of the prehistory of the

north-east of Scotland. The centre building houses a film introduction

to Scottish prehistory and a series of computer-generated interactive

displays. Outside there is a range of reconstructions, a prehistoric

tree trail and a 'real' prehistoric settlement on Berryhill - a late

Bronze Age/Iron Age enclosed hilltop settlement with outlying open settlement

partially excavated in 1999. A second season of excavation is planned

for August 2000 and volunteers are welcome. The site is particularly

appropriate for illustrating continuity of use of a relatively dry,

level low hill in what, until recently, was quite wet lower ground.

Late Neolithic/Bronze Age flintworking on the hill probably indicates

intermittent, pre-settlement, use of the hill which was also reused

in the post-medieval/early modern period for a very small croft.

Hilary Murray

|

|||||||||||||

|

REFLECTIONS

FROM THE SECRETARY Retirement from Council as Secretary in May provides the opportunity

to reflect on how the Society has changed over the past decade. The

Society is often viewed as a traditionalist and relatively slow moving

organisation but it has tried to move with the times whilst maintaining

its high standard of publications and events. Bob Bewley (I'm sure all members will join me in voting a huge round of thanks to Bob for all his hard work on behalf of the Society over the past decade - ed.)

|

|||||||||||||

|

RUN OF PPS BACK NUMBERS FOR SALE A rare run of back numbers of PPSEA/PPS back numbers from 1908-1994

is for sale. Volumes for 1908-1956 are bound in 14 volumes, grey cloth,

with 1956-94 in original wrappers. All in very good to fine condition.

|

|||||||||||||

|

Iron Age Research Student Seminars: 3.6.00-4.6.00

The Prehistoric Archaeology of Kent: recent discoveries: 3.6.00

Islands: dream and reality: 29.6.00-2.7.00

Tall Stories? Broch studies, past, present & future: 7.7.00-10.7.00

Lithic Studies in the year 2000: 8.9.00-11.9.00

European Association of Archaeologists: 10.9.00-17.9.00

|

|||||||||||||

| |

The Prehistoric Society Home Page |