Crucial sex hormones re-routed by missing molecule

29 November 2010

Links:

bbsrc.ac.uk/" target="_self">BBSRC

bbsrc.ac.uk/" target="_self">BBSRC

A hormone responsible for the onset of

puberty can end up stuck in the wrong part of the body if the nerve pathways

responsible for its transport to the brain fail to develop properly, according

to new research led by UCL scientists.

By tracking how nerve cells responsible for regulating sexual reproduction in mice find their way from their birth place in the foetal nose to their site of action in the adult brain, the researchers found that if a certain molecule is missing, then these pathways are not formed correctly and gonadotropin releasing hormone (GnRH) can become lodged in the nose or the forehead rather than in the brain, where it is needed to control the menstrual cycle in females and testosterone production in males.

The authors of the research include Dr Christiana Ruhrberg (UCL Institute of Ophthalmology), Professor John Parnavelas and Dr Anna Cariboni (UCL Department of Cell And Developmental Biology).

Speaking about the findings, published today in Human Molecular Genetics and funded by the Biotechnology and Biological Sciences Research Council (BBSRC), co-investigator Dr Ruhrberg said: "We discovered that a molecule essential for the growth of the nerve cables that transmit odour and pheromone signals from the nose to the brain is also crucial in the development of the highways responsible for transporting other nerve cells that make the sex hormone GnRH.

"We found that in mice with an inherited deficiency in the molecule SEMA3A, these highways did not lead to the brain, but instead formed impenetrable tangles outside the brain. This means that the nerve cells making GnRH are unable to get to their final destination and instead become stuck in the nose or forehead."

As a result the researchers found that the testes of mice lacking SEMA3A did not grow properly and the adult males were infertile. These findings have important implications for the study of Kallmann's syndrome and related genetic disorders that cause infertility.

Professor Douglas Kell, BBSRC Chief Executive said "This study highlights the importance of understanding the very earliest developmental processes of the brain, including how and where cells develop, how they migrate and how and where they mature. Such fundamental bioscience research helps drive medical advances by providing clues about the development of a variety of disorders which present huge challenges to individuals, their families and our wider society."

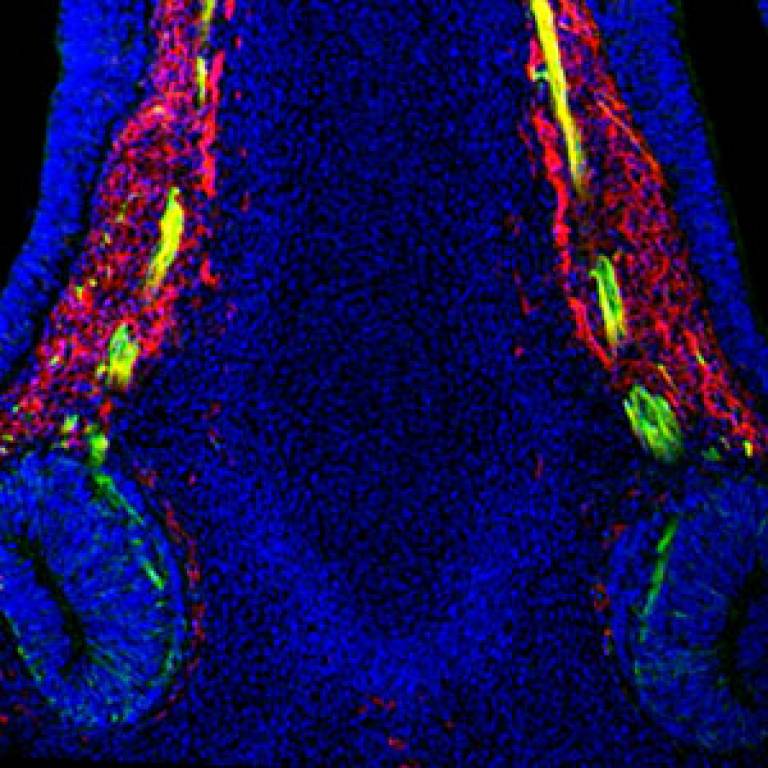

Image: An optical section through a normal mouse nose showing the route the nerve cables (yellow) normally transport the GnRH through the nose (blue). The red shows the corridor inside the nose through which the nerve cables like to travel. (Credit: Dr Anna Cariboni)

UCL Context

The Research Department of Cell and Developmental Biology is one of the largest departments at UCL. It is part of the Division of Biosciences in the Faculty of Life Sciences and brings together excellent, internationally competitive cell, developmental and evolutionary biologists to provide coherence of research strategy in the exciting fields of Life Science.

The UCL Institute of Ophthalmology aims to develop new treatments for eye disease out of a large and varied foundation of basic research. Its researchers work very closely with Moorfields Eye Hospital NHS Foundation Trust and are part of UCL Biomedicine, one of the largest aggregates of biomedical expertise in the world.

Related news

Stem cell technique offers new

potential to treat blindness

Cells' grouping tactic points to new

cancer treatments

Close

Close