Out of the ears of babes

25 April 2007

This spring marks the first anniversary of the national hearing test for newborns.

600,000 babies across the UK have now donned tiny earphones, oblivious to the test that could change the rest of their lives. The hearing test is the first national screening programme introduced by the NHS in 50 years, and has been hailed by the National Deaf Children's Society as 'the most significant opportunity for deaf children in 100 years'. And it all started 30 years ago with Professor David Kemp, a physicist now working at the UCL Ear Institute.

600,000 babies across the UK have now donned tiny earphones, oblivious to the test that could change the rest of their lives. The hearing test is the first national screening programme introduced by the NHS in 50 years, and has been hailed by the National Deaf Children's Society as 'the most significant opportunity for deaf children in 100 years'. And it all started 30 years ago with Professor David Kemp, a physicist now working at the UCL Ear Institute.

In July 1977, Professor Kemp was working at the Royal National Throat, Nose and Ear Hospital when he took a miniature microphone from an old hearing aid, stuffed silicone putty around it to close off the ear canal and listened to a single pure tone via headphones. Milliseconds later, a reading appeared on the screen before him, proving, as he suspected, that the ear actually gives out sound when it hears one. The experiment settled the debate as to whether the ear reacts physically to sound, and provided the first recording of the tone produced by the ear, which became known as the 'otoacoustic emission'.

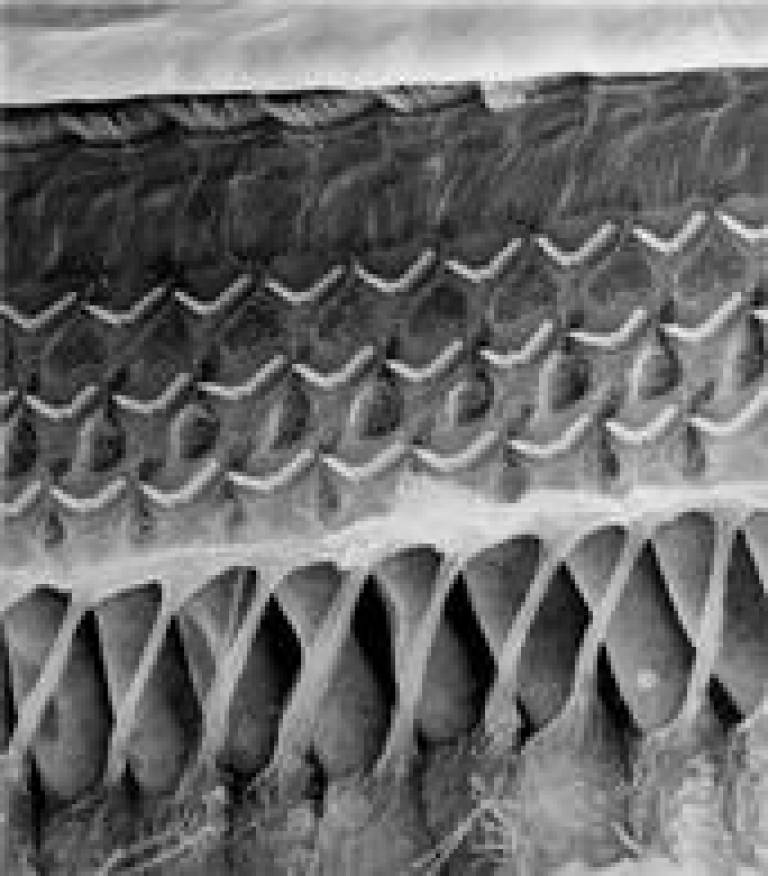

"If you look at a picture of the inside of a cochlea, it looks like a microchip - and it is a kind of signal processing device," explains Professor Kemp. "The ear actively handles sound, reacting with vibrations of less than an atom that can be picked up. It's a kind of positive feedback, which is absent in ears with hearing loss."

Professor Kemp's findings were greeted with scepticism by his peers, but he remained undeterred, given their potential to revolutionise the lives of the 900 deaf children with permanent hearing loss born in the UK every year.

At the time, hearing tests consisted of health visitors clicking their fingers or shaking rattles behind babies' heads to check for a reaction. Those who didn't respond or with a heightened risk of deafness were referred for an expensive hospital-based test, which recorded brain activity in response to sounds. However, the test could only be conducted when babies were old enough to support and turn their heads, at around eight months. Furthermore, the results could be deceptive: the health visitor's perfume or shadow could give the game away, with the result that half of all deaf children 'passed' both the distraction and brain response tests, and a quarter were only identified as deaf when they were three and a half years old.

This late diagnosis can have a devastating effect on language, social and educational development.

"By the age of one, we have learnt all the speech sounds of language," says Professor Kemp. "If children miss out on a hearing aid in their first two and a half years, they lose the ability to learn language naturally, so it's vital to get a hearing aid on a child as early as possible to reduce the handicap."

In 1978, Professor Kemp's sound emission screening test was patented, but manufacturing problems meant that it was only in 1987 that Peter Bray developed technology compatible with IBM computers at the Institute of Laryngology & Otology (the ILO, which became part of UCL the same year).

After buying back the patent rights from the government at considerable cost, Professor Kemp formed the company Otodynamics Ltd and the following year began to sell the technology - the ILO88 - by mail order in return for royalties to support hearing research at the ILO and the Royal National Throat, Nose & Ear Hospital.

The technology met with immediate success. That year, Whipps Cross Hospital in Leytonstone became the first hospital in the world to offer routine newborn hearing screening using the new system. The US government approved it for sale, and recommended it for a national universal screening programme in 1993. Orders came in from hospitals and research laboratories around the world, leading to a Queen's Award for export achievement in 1993, and again in 1998.

The design has evolved over the years. In 1993 the team developed a portable battery-powered version that worked without a computer, enabling health visitors to test babies at home. The handheld systems developed in 1995 are only now being phased out. Slightly larger and only a little heavier than an early mobile phone, these early models proved to be simplicity itself. When the two earphones are plugged in, one sends a series of soft, rapid clicks into the ear not unlike the beating of a moth's wings, while the other measures the sounds given out in response by the ear itself. The system takes hundreds of readings within the space of a minute to obtain an average, before a green light appears under 'Yes' or 'No'.

These models began to be used in the UK in 1995, but it was only ten years later that the British government gave the go-ahead to a universal screening programme, the year that Professor Kemp received a lifetime achievement award from the US National Association of Special Instrument Distributors.

"The UK is slower but systematic," says Professor Kemp pragmatically. "We are now leading the world in quality control." The model in development will feed test results into NHS record systems electronically, automatically linking the results with the baby's name, time of test and other details, which are currently entered into NHS databases manually.

The system will doubtless be refined further, but Professor Kemp's discovery has already changed the course of thousands of lives. The average age of diagnosis of deafness has fallen from two and a half years to three months, when customised hearing aids can be fitted. This early detection means that supporting professionals, parents and the children themselves can begin earlier on the enormous effort required to advance their language development, potentially enabling them ultimately to speak indistinguishably from those without hearing difficulties. As if it needed further recommendation, the universal screening programme costs half of the rattles and bells system and picks up on deafness in twice as many babies. Quite something to make a noise about.

Image 1: The organ of Corti, the core sensory organ in the cochlea

Image 2: Professor David Kemp at the 2007 American Academy of Audiology meeting

By Lara Carim, UCL Communications

Close

Close