North-South Divide: Sir Michael Marmot

24 August 2017

'Alarming' rise in early deaths of young adults in the north of England - study Recent findings highlight the need for increased investment in the north, warn experts, as research into mortality rate reveals the widening north-south divide.

Photograph: Owen Humphreys/PA Archive/Press Association Ima

Although researchers say the reasons behind the trend are unclear, inequalities have been rising, in particular for those between the ages of 25 and 44 .

Researchers say that since 1965, about 1.2 million more people have died before the age of 75 in the north of England than in the south, taking into account differences in population.

And the team warns that the gap in premature deaths is growing larger

- revealing a particularly "alarming growth" among younger adults and

those nearing middle-age.

"Between the ages of 25 and 44 there have been rising inequalities," said Iain Buchan, professor in Public Health Informatics at the University of Manchester and a co-author of the study.

While it is not clear what is behind the trend, Buchan said the

findings highlight the need for policies to increase investment in the

north of England

"There is higher attainable health in the north, as shown by the higher attained health in the south - therefore invest in the north," he said.

Published in the Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health by Buchan and colleagues at the University of Manchester and the University of York, the latest study built on previous work by the group, which looked at trends between 1965 and 2008. The new study extended the findings to 2015, to cover the period since the recent recession.

To investigate the north-south divide, the team split England into "north" and "south", with the latter comprised of the East, South East, South West and London. Using data from the Office for National Statistics, they then combined figures on the numbers of deaths in each region with population estimates.

Overall, premature deaths fell in both the north and the south in the second half of the 20th century. However the study revealed that the decline has levelled off for both since 2010 - the same year at which the rate of increase in life expectancy in the UK began to stall, according to recent research.

"[It is a] stagnation of five decades of improving mortality," said Buchan.

By drilling down into the figures by age group, the team then revealed the widening of the gap among younger adults.

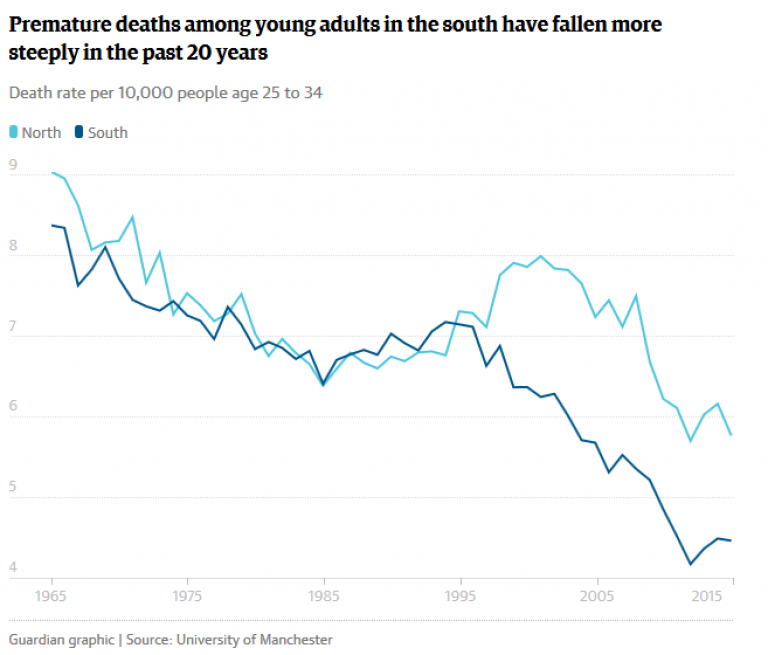

Once factors including age, population size and sex were taken into account, there were 8% more deaths among those aged 25-34 in the north in 1965 but just 2.2% more in 1995. However in 2015, 29.3% more 25-34-year-olds died in the north than the south.

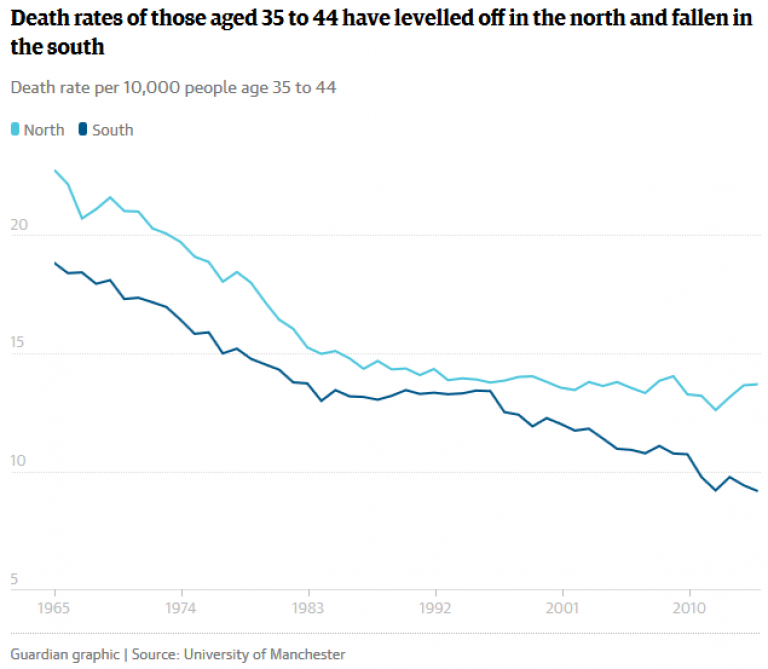

For those aged 35-44, the number of deaths was almost 21% higher in the north in 1965, falling to just 3.3% higher in 1995 before rising to almost 50% higher than the south in 2015.

That, said Buchan, suggested the south was doing better at tackling common chronic disease deaths that typically start to become more common from the age of 40.

While the authors do not explore the reasons behind the deaths, they note that the most common causes of death among young adults include suicide, poisoning, traffic accidents and liver disease.

And although the research did not find any obvious effects of economic recession on the trends, Buchan said investment in the north was of paramount importance.

"A sticking plaster might be education, improvement of interventions around alcohol misuse and the other common causes associated with young people's deaths - but that doesn't tackle the root cause of the social and economic environment," he said.

Sir Michael Marmot, Professor of Epidemiology and Public Health within the Institute of Epidemiology and Health Care, was not involved in the study and said that the research showed the north-south divide has been amazingly persistent. "It is really astonishing how long it has gone on for," he said, adding that other research has shown that the divide is worse for those of lower socio-economic status.

While Marmot said that it was difficult to link changes in mortality

to changes in government policy - not least because it is not known what

the lag times might be - he said it was highly likely that the

disadvantage in the north was social and economic. He added that the

2010 Marmot review laid out a six-point strategy for combating

inequality that including better early childhood development, better working conditions and education.

Richard Wilkinson, co-founder of the Equality Trust

and emeritus professor of social epidemiology at the University of

Nottingham, said he was not surprised by the results, pointing out that

inequalities rose during the 1980s, and added that austerity was making

the north-south divide worse. "The main cuts are to the cities, the

labour areas, which need [money] most," he said.

A government spokeswoman said: "The causes of health inequalities are highly complex but we are taking action by addressing the root social causes, promoting healthier lifestyles and improving the consistency of NHS services etc.

"This government is committed to creating a society where everybody gets the opportunity to make a success of their hard work - regardless of where they are from."

Tweet Close

Close