Robert Keohane: The Man Who Saw Tomorrow in American Power and World Politics

21 September 2015

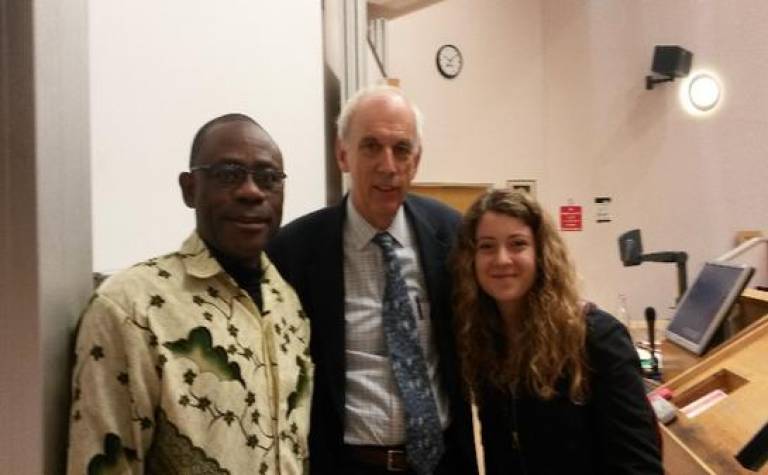

Adagbo Onoja (MSc Global Governance and Ethics) on a GGI keynote lecture with Professor Robert Keohane.

Robert Keohane may not be a name that rings many bells in Nigeria. Indeed, for many Nigerians, the question would almost certainly be: Robert who?. Many Nigerian political scientists, particularly the generation brought up on Claude Ake's Social Science as Imperialism, would most likely not pause at the news that Keohane is coming to town. It was only in the absence of other commitments and thanks to the Global Governance Institute at University College London (UCL) that I found myself in his presence.

Yet, Keohane is widely acknowledged as one of the foremost authorities on international institutions and global order and the foreign policy elite of a hopeful regional power such as Nigeria would do well to take note. His seminal work on contemporary multilateralism is not only grounded in solid scholarship, but also provides a blueprint for ministries of foreign affairs across all major capitals to understand their changing world. His recent intervention on 'contested multilateralism', the topic of his lecture at UCL, provides a unique insight into a new era of global diplomacy.

Keohane made his name in the 1970s in his reformulation of the role of international institutions as a stabilising force in an international order which had been shaken by the surprising fragility of US power in the face of global shocks, echoes of which recur even more forcefully today. Since the 1970s, the US has positioned itself as the global Inspector-General-in-Chief, exercising power, often through the multilateral order, in a way unprecedented in human history. The US emerged in the 1990s as a global hegemon. Keohane identified the role of the US in buttressing the international order, which in turn reinforced the agenda-setting and legitimate authority of the hegemon. One implication he has expanded upon recently is what happens to a system of international security premised on the stabilising force of the US when the hegemon slips, slumps or stumbles?

Robert Lieber's 2011 article, 'Staying Power and American Future: Problems of Primacy, Policy and Grand Strategy', highlights many of the events which rocked the US-dominated global order of the 1970s and spurred Keohane and colleagues on in their reappraisal of the role of international organisations; the first and the second oil shocks, the Iranian Revolution, the subsequent hostage crisis, mounting signs of economic crisis and the rise of Japan as a major world player, to name but a few.

Keohane's answer was to reformulate international institutions as a stabilising substitute for great power hegemony. So the neo-institutionalist paradigm was born. The paradigm does not dispute that international politics is a realm of anarchy with no overarching central authority, but it challenges the assumption that such a setting precludes state cooperation. The role of international organisations in facilitating intergovernmental coordination forms the backbone of his book After Hegemony: Discord and Collaboration in the World Economy, described by Craig Murphy as 'a truly paradigmatic work'. This work has since assumed a totemic status in international relations scholarship and practice, continuing to provide the fundamental coordinates for understanding global political events.

Indeed, many scholars and practitioners may have reached for the book on the day following the UN decision not to endorse the US invasion of Iraq. Once again, Keohane shone a light on the (delayed) effects of institutionalism on hegemony. The US may have proceeded regardless, however it has been at a high cost to its hegemonic legitimacy. As John Ikenberry observed one year later, the invasion had served as 'a geostrategic wrecking ball that will destroy America's own half-century-old international architecture'. In this sense, Keohane saw further than most what the future may hold for American power and world politics in the absence of strong support for a multilateral order.

Debate surrounding Keohane's claims will no doubt continue as new interpretations are advanced and real world anomalies arise. Amidst this debate, Keohane retains his status as, in the words of John Agnew, a 'distinctive theorist'. Notwithstanding Agnew's reputation as a probing scholar at the critical end of the theory spectrum, his appraisal of Keohane underlines his position not only as perhaps the foremost scholar of order and stability of his generation, but also as a 'scholar's scholar'. Forty-five years after first entering the scene, Keohane remains at the forefront of scholarly and policy debate.

His lecture at UCL in May 2015 tabled a new project entitled 'Contested Multilateralism'. Without going into the intricacies of the argument, it is illustrative to consider the momentous news of the launch of the China-led Asia Investment Infrastructure Bank, (AIIB). The AIIB represents a significant challenge to the old economic order underpinned by the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. This new multilateral institution has already welcomed all the major powers of Europe as members, not to mention the big players in Asia. According to Keohane, this is a significant challenge to the multilateral financial architecture which has persisted since 1945. The AIIB can be regarded as a classic example of contested multilateralism, with China establishing a new institutional forum as a vehicle to contest the existing status quo on its own terms. This is not rejection of the multilateral order, but rather a conscious attempt to remake it in the image of an emerging multi-polar global order.

For Keohane, contested multilateralism is a strategy of change, but not necessarily transformational change. It is not the multilateral system which is contested, but rather the specific regimes and operating logics which currently inhabit that space. In this telling, it is a strategy employed by established or emerging powers to cement new coalitions and legitimate sets of practice which lie outside the norm. This line of reasoning was clarified in Keohane's considered response to a question which sought to suggest that 'counter-multilateralism' more accurately captures what we are witnessing.

Notwithstanding Keohane's valuable contribution to the debate in advancing this new concept, it is important to reflect on alternative perspectives regarding its significance and implications. Other observers, especially perhaps those situated in the Global South, may advance a different interpretation. A key motivation for this piece is the importance of identifying and subjecting such new arguments, ideas and doctrines to critical appraisal in the public domain, inviting new insights on an important contribution to thinking about power, global justice and related concerns. To advance a more provocative line of inquiry, contested multilateralism could plausibly be critiqued as a conceptual misdirection, serving to defang the more radical tendencies of the rising powers in Asia, Latin America and Africa and instead conceive of them as status quo actors rather than antagonists of a liberal world order which has traditionally marginalised or excluded them.

In the article Keohane has co-authored with Julia Morse, a colleague at Princeton University, they acknowledge that contested multilateralism is a moving target. As with all attempts to capture a fluid reality, there are few determinative conclusions to be drawn by students of liberal institutionalism as yet. However, contested multilateralism does appear to offer powerful insight into patterns of systemic turbulence present across a range of major global public policy concerns, from cyber governance, to climate change and drug control, among others. Keohane is conscious of the limits of any one frame to capture a global political arena undergoing profound change, reflected in an almost overwhelming multiplicity of principles and practices as power diffuses from nation-states, to international institutions, international personalities (Bill Gates, Bono), and non-governmental organisations.

Unsurprisingly, Keohane was subjected to a barrage of questions following his lecture to which he offered a series thoughtful responses before Dr Tom Pegram, Deputy Director of the Global Governance Institute, brought the seminar to a close. However, Keohane was kind enough to stay behind and continue the discussion with a handful of students who, having no doubt read his many works, were not about to pass up this opportunity to speak to the man himself.

Professor Keohane conducts himself with the practised ease of a veteran. He still teaches actively. He mentioned that he has had Nigerian students in the past and he would welcome more. As the only Nigerian in sight, I take it this was directed at me. It is an 'invitation' I would have loved to take up; the US and Princeton in particular have some of the best minds in political science in the world. But were I to head off to the US after only recently returning to Nigeria from the UK for another academic engagement I would likely be declared a mad man. It has been a privilege to be able to take time out of work to devote myself to expanding my intellectual horizons in the company of scholars such as Robert Keohane. Younger Nigerians who have the resources and an interest in pursuing a liberal institutionalist direction in an Ivy League institution should be encouraged to explore Keohane's invitation. Reading his book, After Hegemony, I was struck by his emphasis on honesty and integrity. From the, albeit brief, time I spent in his company, his enthusiasm and generous response to questions revealed a scholar who does not do arrogance, despite his stature. He is not one of those. We ended up taking pictures.

In the picture: Professor Robert Keohane with UCL alumni Adagbo Onoja and Seda Karaca. Adagbo Onoja is based in Abuja, Nigeria. He can be contacted at: adagboonoja@gmail.com.

Close

Close