This programme aims to provide a historically-based overview of the literature of all periods, together with opportunities to specialise in particular periods of literature, in modern English language, and in non-period courses. Students are encouraged to develop their own interests and may choose from a wide variety of specialisms.

Why study English at UCL?

UCL was the first university in England to teach English at undergraduate level, and since then the English Department's courses have evolved to reflect the twin virtues of breadth (students are encouraged to take a range of papers, and to graduate with a broad understanding of the development of English literature over time) and depth (students have a wide choice of optional papers, which can be taken in any combination, and the provision of different 'sign-up' seminars in many optional courses further encourages students to tailor courses around their own interests, whilst not losing the sense of a wider context).

Free online Study Prep for year 13 students

Please see the UCL online study prep free online course for students in Year 13 who are preparing to study at university.

Open Day Video by Dr Hugh Stevens

Taster Sessions

Dr Charlotte Roberts, Laurence Sterne, The life and opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman (1759-67)

Dr Amy Faulkner, Old English Literature, Unlocking the word-hoard

Dr Kathryn Allan, Literary Linguistics, Foregrounding

Dr Eric Langley, Shakespeare in Plague Time

Dr Hugh Stevens, D. H. Lawrence, Bavarian Gentians

Dr Matthew Sperling, T. S. Eliot, The Waste Land

Student Testimonials

"My time at UCL was transformative. The Department taught me that English is not just about books: it's a way of looking at the world. Studying Literature is about making connections, and, among other things, demands an understanding of history, science, philosophy, visual art, politics and culture. The course grounds you in all these disciplines. As a result, one leaves UCL prepared to tackle any challenge. The staff are brilliant, as is the one-to-one tutorial system. I will be forever grateful to the UCL English Department in general, and my third-year tutor in particular. Studying English Lit at UCL gives you so much more than just a degree". Anna Lamche (BA English Graduate)

“I would highly recommend the English course at UCL. I felt it perfectly combined a broad stretch of literary history with the opportunity to focus on whichever particular time period or author took my fancy, all through the excellent teaching of the English faculty.” John Peatfield (BA English Graduate)

The Tutorial System

This ability to tailor the syllabus around a student's academic interests is most apparent in our tutorial system. UCL English is the only university that teaches English undergraduates one-to-one: something which our students regularly say is the single most important factor in their academic development across their degree, as well as the most enjoyable.

All students are given a tutor in the first year, a different one in the second year, and another in the third year. You will write essays in preparation for fortnightly meetings with your tutor, in which your work will be discussed and your ideas challenged: this is designed partly to improve your writing and prepare you for exams, but also to enable students to research topics for their essays which are of particular interest to them (as long as these fall broadly within the confines of the papers a student is taking that year). The tutorial is thus not only an unrivalled opportunity for one-to-one supervision of your work, but a chance for individuals to pursue personal research ideas, guided by their tutor.

Course Structure

The first year of the English BA acts as a foundation for the two following years, covering major narrative texts from the Renaissance to the present, background texts from Homer to Freud and Barthes, Anglo-Saxon and medieval writings and the study of critical method.

In the second and third year you will study compulsory modules on Chaucer and Shakespeare and choose six further modules, covering literature from the Old English period to the present day. Students must take at least one pre-1800 module and at least one post-1800 module. You will also have the opportunity to study American literature and literature in English from other countries.

First Year

The first-year course consists of four components which taken together constitute a foundation for the further study of English Literature:

- Narrative Texts

This course aims to make sure that all students, whatever options they may later choose, have studied certain major works, and have so gained a preliminary idea of English literary history and its main movements from the early modern period to the present. In addition, the course introduces the study of narrative in the poetry and fiction of this period, and gives students experience of studying complete and complex works in a relatively short time. Works are studied in chronological order.

Current Narrative Texts include Paradise Lost, The Rape of the Lock, Tristram Shandy, The Prelude, Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, The Mill on the Floss, The Waste Land, and Beloved.

- Introduction to Medieval Language and Literature

This course aims to give all students on it an introduction to the study of literature which is written in Old and Middle English, and predates the period of Narrative Texts. By the end of the course students will have an acquaintance with the range and variety of this literature and some fluency in reading it. In addition to completing the chronological range of English literature, this course prepares students for the study of Chaucer in the second year and for the optional medieval courses.

- Intellectual and Cultural Sources

This course aims to give students an acquaintance with a selection of works – not necessarily ‘literary’ or originally written in English – which have been either influential in the formation of English literary and intellectual history, or articulate ideas important in that formation. A knowledge of these works is essential for all three years of the degree course. The course suggests some of the main features of the history of European ideas, and encourages students to acquire some capacity for handling conceptual argument. In addition, some, but not all, of the works in this course either actually influenced, or provide interesting comparisons and contrasts with, some of the texts in the Narrative Texts and Introduction to Medieval Language and Literature courses.

Current Intellectual and Cultural Sources texts include the Odyssey, Oedipus the King, Plato's Symposium, The Aeneid, Ovid's Metamophoses, Dante's Inferno, Utopia, Rousseau's Confessions, A Vindication of the Rights of Women, On the Origin of Species, Nietzsche, Freud, Foucault, Edward Said, and many more.

- Criticism and Theory

This course is introductory, and aims to provide, or reinforce, a grounding in the methodology and history of the subject. The first-term lectures aim to introduce and exemplify some of the indispensable elements of a critical vocabulary. The first-term seminars offer the chance to put some of these elements into practice through commentary and analysis exercises, involving the detailed discussion of unseen passages of literature in various genres and from various periods. The second-term lectures offer a brief historical survey of different ideas of literary criticism and theory from the Renaissance to the present day; second-term seminars explore a selection of these ideas in further detail. Lectures and seminars across both terms aim to stimulate attentive and accurate close reading. Lectures focus on methodology in the first term, and history in the second; seminars in both terms aim to develop and consolidate the close reading skills crucial to the study of literature.

Single honours students follow all these courses, while Modern Language and English students follow the Narrative Texts course and either Criticism and Theory or Introduction to Medieval Language and Literature.

Second and Third Years

The following courses run yearly:

- Chaucer and his Literary Background

Chaucer is the first authorial celebrity to have been working in, and with, the English language. Chaucer’s status – to some extent contrived and political – as the originator of a literary tradition in English, and, initially, of rhetorical and philosophical traditions as well, developed almost immediately after his death. His writings have remained influential through virtually all subsequent periods of English literature, and have fascinated many of the greatest English writers in these periods (and some of the greatest filmmakers of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries too). For all of these reasons, Chaucer is the subject of a core course in the UCL English Department.

To some extent, Chaucer instigated the myth that quickly came to surround him, through his awareness of the celebrity that other authors, ancient and much more recent, had already acquired. Chaucer was steeped in the works of classical writers, especially Ovid, as well as of medieval French poets such as Guillaume de Lorris and Jeun de Meun, the joint authors of the seminal thirteenth-century text Le Roman de la rose, and Guillaume de Machaut, a prolific author of the fourteenth century. Chaucer also knew the writings of Dante, Petrarch and (especially) Giovanni Boccaccio, whose works were the springboard for some of Chaucer’s greatest literary compositions. In the first term of the course, lectures consider what many of these writers, and others, gave Chaucer, and what use he made of their works. This is best seen in his early and later dream vision poems, The Book of the Duchess, The House of Fame, The Parliament of Fowls and The Legend of Good Women, and in what is in many ways Chaucer’s masterpiece, the philosophically grounded love story Troilus and Criseyde.

Writing in the Middle Ages took many different forms, and in his best-known work, The Canterbury Tales, Chaucer puts its variety on display. Chaucer’s tales include romances and fabliaux, saints’ lives and tragedies (in the medieval understanding of the term); the tales are told using a range of different poetic media, as well as, in some cases, prose. In composing examples of almost every genre of narrative known to the Middle Ages, in a medley of forms, Chaucer showcases his own virtuosity as a writer. The second term of the course is devoted to The Canterbury Tales, which opens up the richness of medieval literature, together with the new possibilities for writing in English that Chaucer introduced.

Teaching is through weekly lectures plus four two-hour seminars in each of the autumn and spring Terms. By the end of the course, students will have acquired a comprehensive knowledge of Chaucer’s œuvre, an awareness of the dimensions of Chaucer’s reading, and familiarity with the generic and formal variety of medieval writing, as mediated through the English language. Students will also have gained fluency in reading Middle English.

The Final examination is an open-book paper lasting six hours. A plain text of Robinson’s second edition of the complete works of Chaucer is provided for each candidate. In the examination, students are expected to spend much of their time preparing their answers, and are not required to write more than they would for a three-hour paper.

- Shakespeare

The aim of this third-year core course is to introduce students to the study of Shakespeare at a high level. Its objectives are to cover as many plays and poems as is consistent with some depth.

Weekly lectures are supported by fortnightly seminars which investigate individual plays in detail. Four set plays are set for special study each year: these form the basis of the autumn term seminars and are examined in a separate section on the Finals examination paper. The spring term seminars are sign-up, offering students a choice from five or six topics. These sign-up seminars offer opportunities for teachers to share their specialist interests, and for students to develop their own personal expertise.

An introductory lecture sets out the chronology and canon of Shakespeare's work, and basic textual and editorial information. Lectures on each of the four set plays are given in the autumn term; the rest of the lectures in both terms cover further plays, poems, and a variety of critical methodologies for studying Shakespeare. By the end of the course students should feel that they have substantial knowledge of a range of Shakespeare’s works and are familiar with key topics in current Shakespeare studies.

A basic reading list is issued at the start of the course, and lecturers and seminar-leaders recommend further reading. The Final examination is an open-book paper lasting six hours, with a copy of the complete works (Arden edition) provided for each candidate. The aim is to encourage candidates to give considered answers, to show how they can work closely with Shakespeare’s works, and to show how their work on the course has equipped them to think on their feet about Shakespeare. There are commentary as well as essay questions on the set plays in the first section of the exam.

- Commentary and Analysis

(This course is not available to Modern Language and English students)

This course, consisting of two general lectures and four small-group compulsory seminars each term, offers third-year students the opportunity to practise their critical skills in preparation for the exam which most will be sitting at the end of their final year. Students will be reacquainted with a range of issues and approaches pertaining to the close reading of literature, and have occasion to hone their critical and technical skills.

Small-group seminars will invite responses to passages in prose, poetry, and drama spanning a variety of periods. Lectures will provide an overview of productive approaches to unseen texts.

By the end of the course, students will have developed greater skill and confidence in their ability to analyse passages in detail and to organize their observations into orderly and effective critical essays.

Examination is by means of a six-hour paper, calling for comment on passages of prose, poetry, or drama, taken from any period of writing in English. Critical Commentary and Analysis must be followed in the third year, unless a student takes advantage of the allowance to choose an alternative course if taking three or more medieval or language-related optional courses.

Chaucer is compulsory in the second year, and Shakespeare in the third.

Students should also take Critical Commentary and Analysis unless they are sitting three or more medieval options: in these cases, Critical Commentary is an optional paper.

Students then select five (or six, if they have not taken Critical Commentary and Analysis) further courses across the two years of study. Below is a list of current options.

(Please note that details are subject to change and the department reserves the right to withdraw a module).

Many of the larger courses also have different seminar options within them, which students can choose between based on their particular interests ('sign up seminars').

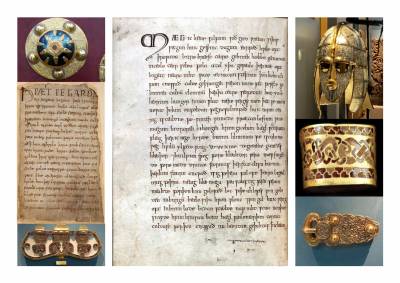

- Old English I: Stories from the Heroic Age

The earliest English literature was written in Anglo-Saxon England from the late 600s to the reign of King Alfred the Great (871-99). Between faction-fighting at home and Viking invasions from abroad, an evolution took place in these centuries in which many warring aristocracies from Northumbria to Kent were slowly reduced to a smaller number of kingdoms with Wessex at their head. This course gives an opportunity to study the rich variety of the Old English poetry and prose of the earlier period in which tribal warfare, fierce Christianity and tangled politics are reflected in traditional and contemporary tales of mortal combat, spiritual ecstasy and the love of dangerous men and women. Poems including Beowulf, The Wanderer and The Seafarer, are read in full or in extract alongside Bede's account of Cædmon, the earliest named poet in the English language, stories involving ambush and assassination from The Anglo-Saxon Chronicle and some of the earliest English prose from the reign of King Alfred. The aim of this course is to provide students with sufficient knowledge of Old English language and the background to the period to enable them to analyse these texts in terms of both their literary value and their social and cultural context.

Teaching consists of twice-weekly one-hour seminars. The course is examined by a three-hour written paper containing translation and commentary of texts already studied in class, and essay questions.

(NB: it is not possible to be examined by Course Essay for this course.)

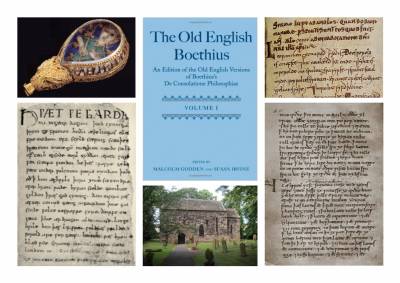

- Old English II: Books from the Era of Invasion and Reform

Taking the reign of King Alfred as its starting point, this course covers a period where the identity of the English nation is slowly emerging. Students will encounter a body of prose literature of the highest quality. Along with its artistic richness, much of this literature has a political and didactic agenda. In Alfred's Preface 'On the State of Learning in England', for example, we will see how English literature became a vehicle to promote the identity and prestige of the nation. The ninth-century literary renaissance also witnessed an interest in translating various classical works into English. The Old English Boethius, with its far from literal translation of its source, will give students an insight into the preoccupations of contemporary readers and writers.

From later in the period, we will study lives of English saints – a sort of celebrity culture for its age, but with a moral slant – for example the Life of St. Æthelthryth, by Ælfric, abbot of Eynsham. Dazzling rhetorical richness can be found in the Sermo Lupi ‘Sermon of the Wolf’ written during the final Viking War as a public address by the fire-eating Archbishop Wulfstan of York.

Amongst the poetry on offer, Judith imaginatively retells the apocryphal tale of the woman who seduces then beheads a general to save her town. The Battle of Brunanburh (the defeat of Vikings from Ireland near the Wirral in 937) and The Battle of Maldon (an English defeat followed by suicide action in a battle with Norwegian raiders in 991) reflect the impact of the Viking invasions, exploiting heroic culture in the context of contemporary historical events.

The course assumes some prior knowledge of Old English (such as the first-year Old English course).Teaching consists of twice-weekly one-hour seminars. The course is examined by a three-hour written paper containing translation of and commentary on texts already studied in class, and essay questions

(NB: it is not possible to be examined by Course Essay for this course).

- Middle English I

This course focuses on literature in English from the time of the Norman Conquest up to and including the period in which Chaucer was writing, the second half of the fourteenth century. One of its aims is to contextualise Chaucer’s achievement by looking at writing in English in the centuries and decades that preceded his literary career. It also aims to situate Chaucer in the great flourishing of English literature that was taking place in his day: to look at some of the other great ‘Ricardian’ literature (literature written during the reign of Richard II) that was produced even as Chaucer was writing. It therefore forms an excellent complement to the core course ‘Chaucer and his Literary Background’.

The course considers such matters as treatments of the British past in romances and poetic histories that were composed in the Middle English period, including texts that debut the story of King Arthur and his Round Table in English; the writing of fabliau in English before Chaucer; and English writing for female religious in the early thirteenth century – writing that is fully conscious of the gender of its audience. Works of the so-called ‘Alliterative Revival’ – poetry that developed insular traditions of verse – will also be studied, including Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and other writings thought to have been written by the author of Sir Gawain, including Pearl, a moving dream vision poem in which the narrator tries (with only partial success) to come to terms with the death of his infant daughter, and Patience, the Gawain-poet’s unique take on the Old Testament story of Jonah and the whale. The Confessio Amantis, a great treasure-book of tales by Chaucer’s contemporary John Gower, is another component of the course.

By the end of the course, students will have been made aware of the diversity of writing in English in the Middle Ages, and of many of the literary traditions from which English writing that was produced in the period grew. They will also have extended their competence in reading Middle English.

- Middle English II

The particular focus of this course is literature in English that was composed in the later part of the Middle English period. One of its aims is to explore writing that was produced in the wake of Chaucer’s literary achievement, and that was influenced by this. But it also explores writing that was produced outside the sphere of influence of Chaucer’s works: devotional and dramatic literature, for example. For both of these reasons, the course extends material studied for the core course ‘Chaucer and his Literary Background’.

In addition to looking at such writers as Thomas Hoccleve and William Dunbar, admirers but also potentially questioners of Chaucer’s poetic œuvre, the course examines some of the works produced by female authors in England in the late-fourteenth and the fifteenth centuries: the Revelation of Love of the woman visionary Julian of Norwich, for example, and the equally remarkable Book of Margery Kempe, which presses the claims to sanctity of one serial pilgrim, and mother of fourteen children, from East Anglia. A major component of the course is medieval drama, both the mystery cycles that were performed in prosperous English towns in the late Middle Ages, and ‘morality plays’, much more cerebral and stylised examples of dramatic writing that continued to be produced in the ‘early modern’ era, and that were influential on the playwrights of other forms of drama that were written then. Late-medieval England was a place of protest against authority, both political and religious, as well as deference to it, and the course also looks at, for example, the challenges to the official doctrines of the Church issued by the followers of the Oxford theologian John Wyclif.

By the end of the course, students will have been made aware of the variety of both writing and the individuals who produced it in England in the Middle Ages. They will also have extended their competence in reading Middle English.

- Renaissance Literature

This course, focusing on literature written between 1520 and 1625, covers one of the most innovative periods in English literary history. This century or so of literature – witnessing a frenzy of formal experimentation and literary achievement – looks backwards to its classical and medieval inheritance, glances sideways to daring new developments in continental literature, and in its remarkable inventiveness reaches forwards to leave its stamp on the genres, styles, and idioms of future centuries. This paper, along with those for Seventeenth Century Literature and Eighteenth Century Literature, is one of a suite of courses covering a period of literature that critics increasingly label “early modern”, in recognition of its formative role in shaping later literary and intellectual culture. Renaissance Literature 1520–1625 stretches from the Tudor Reformation to the birth of science writing, and it sees the emergence not only of new literary forms but also of English literary theory itself, as writers like Sir Philip Sidney began to consider – and sculpt – a distinctly English vernacular literature. Beyond producing Shakespeare (who has his own paper) and a wealth of contemporary luminaries who hold their own against him, the period flaunts an embarrassment of forms and genres: in poetry, sonnets, pastoral, epic romance, elegies, epyllia, and epigrams; in drama, Elizabethan revenge tragedy, Jacobean tragicomedy, domestic tragedy, city comedy, and masques; and in prose, utopian literature and travel writing, sermons and satires, scientific and philosophical writing, letters and diaries, rogue literature, the essay, romances, novellas, and proto-novels.

The course is taught through a combination of lectures, seminars, and tutorials. Some lectures will discuss single authors, and others will address specific genres, intellectual and cultural contexts, or literary themes and movements. Autumn seminars will cover a range of set works, and in the Spring students may choose from a number of more specialized sign-up seminars. In recent years, scholars and students have produced exciting work on rhetoric, eloquence, and inarticulacy; plainness and linguistic excess; restraint and wantonness; crises of identity, perception, and conscience; the history of subjectivity, emotions, and memory; cultural identity, nationhood, and transnationality; scepticism, magic, and the supernatural; the city, travel, and discovery; literary fame and the birth of “the author”; types and habits of reading; history and historiography; responses to classical literature and myth; original performance and early audience responses ... to name but a few. Students are encouraged to engage with any writers or works from the period that appeal to them, but authors receiving particular attention on the course will include: Thomas More; Thomas Wyatt; Philip Sidney; Mary Sidney; Edmund Spenser; Queen Elizabeth I; Isabella Whitney; Christopher Marlowe; Robert Southwell; Thomas Nashe; Samuel Daniel; Michael Drayton; John Donne; Ben Jonson; Elizabeth Cary; John Webster; Thomas Middleton; Mary Wroth; and Francis Bacon.

Examination is by means of a 3-hour written paper, or by Course Essay if preferred and if no other Course Essay is being submitted by the candidate in that year.

- The Seventeenth Century

The course addresses the literature of the seventeenth century, tightly defined as the period running from the accession of Charles I in 1625 through the Civil War (1642-9) and the Restoration of the monarchy under Charles II (1660) to the end of the so-called ‘early-modern’ era in 1700. This was an age of political and cultural revolution and counter-revolution, and its literature is equally searching and seismic. Towering over the century as its literary colossus is the figure of Milton whose forty-year career encompassed, in addition to Paradise Lost, conceptually and generically radical variants of the entire gamut of the period’s poetic, dramatic and prose modes. The period’s other major geniuses include: Herbert, Marvell, Dryden, Rochester and Congreve. Beyond these familiar names, recent scholarship has significantly expanded and diversified the seventeenth-century literary canon, in particular calling attention to the achievements of the pioneering women writers of the age, Margaret Cavendish, Lucy Hutchinson and Aphra Behn, and recovering the work of visionary extremists such as the ‘Ranter’ Abiezer Coppe and eccentrics like Sir Thomas Browne, arguably the most singular stylist in the history of English prose. This diversity will be fully reflected in the course, whose manageable chronological span will ensure that students can encounter the literature of the seventeenth century in all its fertile variousness.

Seminars in the autumn term will address the four 'set texts', chosen to introduce students to the principal genres and styles of the period across its full chronological range. In the spring term, students will have the opportunity to choose from a range of optional seminar courses, focusing either intensively on a single major author (e.g. Milton or Dryden) or else exploring the development of a particular literary mode (e.g. drama) or recurrent preoccupation within the period (e.g. revolution or sexuality).

Lectures in the course will alternate between treatments of single authors and more broad-based accounts of schools or movements (e.g. ‘Civil War literature’; ‘Restoration Comedy’). The key historical divide of the Restoration will provide a natural hinge between the two terms, with lectures in the autumn concentrating on writers and topics from before that divide, and those in the spring addressing authors and themes from after it.

Examination is by means of a 3-hour written paper, or by Course Essay if preferred and if no other Course Essay is being submitted by the candidate in that year.

- The Eighteenth Century

The course focuses on literature written between 1700 and 1789: from the turn of the eighteenth century to the eve of the French Revolution. This period was a time of extraordinary experimentation in literature, culture and the arts and of revolutionary development in the study of humankind (a process sometimes referred to as ‘the Enlightenment’). The literature of this period includes the very first examples of genres, modes and processes that now dominate our literary scene: the rise of the novel, for example, provides a unique opportunity to study a major genre from its inception, while the establishment of professional authorship permanently altered the dynamics of literary production. At the same time, innovation resulted in works that defy definition. Students will have the opportunity to study texts that transcend generic categories, are intellectually and formally subversive, and which challenge the standards and assumptions of the culture in which they were produced (including works by Swift, Fielding, Sterne and Johnson).

The course is taught by means of a combination of lectures, seminars and tutorials. Some lectures will focus on single authors; others may consider larger themes or literary groupings, such as ‘peasant poets’, journalism or the essay. Seminars in the autumn term will cover a range of set texts, and in the spring term students may choose from a number of ‘sign-up’ seminars which may include topics such as ‘the novel’, ‘satire’, ‘comedy’, ‘prose’ or ‘women writers’. Students are encouraged to study any literature from the period that appeals to them, but authors that may receive particular attention on the course include: Addison, Steele, Defoe, Leapor, Gay, Fielding, Pope, Swift, Montagu, Haywood, Richardson, Sterne, Sheridan, Goldsmith, Thomson, Gray, Burney, Johnson, Boswell, Cowper, and Burns.

Examination is by means of a 3-hour written paper, or by Course Essay, if preferred and if no other Course Essay is being submitted by the candidate that year.

- The Romantic Period

The Romantic period was a time of profound social change and of an extraordinary richness in writers of genius. The course attempts to do justice to both aspects, with an approximate alternation of lectures on individual writers and wider topics. It begins by situating the literature of the period historically, outlining its inheritance from the eighteenth century as well as its central importance for all that follows. Subsequent lectures introduce a number of crucial cultural issues: the impact of revolutionary politics, constructions of gender, understandings of sexuality, the role of literature in times of crisis, satirical reaction against Romanticism; and a number of genres: ballads, Jacobin novels, Gothic novels, autobiographical writings. The remaining lectures will be on some of the major writers of the period.

In the autumn term each seminar leader runs an individually chosen programme of four seminars selected from the writings of a number of centrally important writers, such as Blake, Godwin, Wollstonecraft, Wordsworth, Coleridge, Scott, Byron, Austen, Shelley and Keats. Students are encouraged to use the seminars as a basis for exploring the period more widely, and to read in Romanticism: An Anthology (edited by Duncan Wu), as a good sampler and guide to further reading. Seminars in the second term are of two kinds: investigations of genre (such as Gothic novels) and in-depth studies of single authors (such as Keats and Austen).

Examination is by means of a 3-hour written paper, or by Course Essay, if preferred and if no other Course Essay is being submitted by the candidate in that year.

- The Victorian Period

This course explores the literature as well as the cultural, historical, and socio-political contexts of the period ranging from 1830 (when Tennyson’s first volume of poems was published) to 1900 (the last months of Queen Victoria’s reign before her death in January 1901). Often described as ‘the Age of the Novel’, the course naturally devotes considerable space to nineteenth-century fiction, but also pays close attention to the directions taken by poetry and non-fiction.

In the Autumn term, lectures include some overviews of the period as well as, principally, lectures on all the set texts. Seminar groups study at least four of the set texts. (In 2016-17, the seven set texts were Tennyson’s Selected Poems, Brontë’s Villette, Dickens’s Great Expectations, Browning’s Selected Poems, Eliot’s Middlemarch, Christina Rossetti’s Selected Poems, and Hardy’s Tess of the D’Urbervilles. Set texts are subject to change.)

In the Spring term, lectures cover a wide range of authors (such as Henry James and Oscar Wilde), genres (such as sensation novels and science fiction) and topics (such as sexuality, the railway, and Empire). Spring term seminars are sign-up options; options in the past have included ‘Victorian Poetry’, ‘Great Victorian Novels’, ‘The Victorians and Art’, ‘Dickens’, ‘The Brontës’, ‘HG Wells’, ‘The Fin de siècle’, ‘Sensation and Crime Fiction’, ‘The Big Smoke’ and ‘Exoticism and the Supernatural’.

Examination is by means of a 3-hour written paper, or by Course Essay, if preferred and if no other Course Essay is being submitted by the candidate in that year.

- American Literature to 1900

From the early days of colonisation and captivity narratives to the extraordinary literary renaissance of the nineteenth century, American literature grappled with issues of race, gender, democracy, consciousness, vision, urban life, national identity, power and trauma which remain deeply relevant to American culture and society today. This course begins with the Jamestown colonists and the Puritans, who envisaged their new world as a ‘city upon a hill’. It gives you the chance to uncover the origins of the American autobiographical tradition and the gothic novel before focusing on the great American literature of the nineteenth century. In 1838, Ralph Waldo Emerson proclaimed to Harvard’s Divinity School that: ‘always the seer is a sayer’. This was a period in which the role of the writer took on new significance in contexts of Transcendentalism, social utopianism and restless spiritual quest. Abolitionism gained new energy and purpose as fugitive slaves like Frederick Douglass revealed the unmitigated horrors that continued to dominate in the South. In its middle decades, the country exploded in civil war and the world watched, entranced, to see if the fragile experiment of American democracy would survive and whether it would be slaveholding or free. Walt Whitman and Emily Dickinson produced strikingly original poetry profoundly engaged with their own historical moment, Moby-Dick and The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn laid an early claim to the status of the Great American Novel and unprecedented levels of immigration swelled the cities and gave rise to a particularly urban fiction in which, by the end of the nineteenth century, everyday life on the streets became, for the first time, something which might be seen to matter.

Each term consists of lectures on six set texts and related topics and authors plus seminars on four of the six set texts. One of the set texts for the Autumn term is a selection of emancipation narratives, some of which are in the Norton Anthology, one of which is available as a book and the rest on a PDF on moodle. The course engages with a range of writing, including political writing, oratory, poetry, prose, the short story and the novel. Authors include John Smith, Mary Rowlandson, Benjamin Franklin, Jonathan Edwards, Thomas Jefferson, Charles Brockden Brown, George Moses Hornton, Nathaniel Hawthorne, James Fenimore Cooper, Sojourner Truth, Frederick Douglass, Margaret Fuller, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, John Greenleaf Whittier, Horace Greeley, Abraham Lincoln, Frances Dana Barker Gage, Edgar Allan Poe, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, Herman Melville, Mark Twain, Kate Chopin, Henry James, Charles Chesnutt and Stephen Crane. There is an extensive online reading list of set texts and further reading which you are encouraged to browse in order to get a sense of the range and scope of this course.

Examination is by means of a 3-hour written paper or by course essay, if preferred, and no other course essay is being submitted by the candidate in that year.

- Modern Literature I

In 1900, various European countries – Britain, France, Germany, Austria – were competing with each other for imperial supremacy. Over the next five decades (as W. B. Yeats wrote in ‘Easter 1916’), ‘All changed, changed utterly’. In 1950 these European Empires had collapsed, or were in the process of collapsing, and Europe was divided by the ‘iron curtain’. Between 1914 and 1945 there were two world wars, the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia, the Wall Street Crash and the Great Depression, the rise and fall of Fascism, aerial bombardment and destruction of cities, atom bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and the Holocaust. World War Two was followed by the ‘Cold War’, and the world was still troubled by what Sigmund Freud, in a famous letter to Einstein, called the ‘well-founded dread of the form that future wars will take’.

The literature of this period is remarkable for its exciting explorations of race, gender, sexuality, nationalism, and conflict. The first three decades of the century saw the emergence of ‘modernism’, a difficult, self-consciously experimental literature. This course puts modernism at its centre, but also explores the ‘margins’ of modernism, and asks what happened after modernism. In the Autumn term lectures discuss our eight set texts: we study four literary figures who are absolutely central to modernism - W. B. Yeats, T. S. Eliot, James Joyce and Virginia Woolf - but we also enlarge our modernist map, reading works by Jean Toomer, Jean Rhys and Elizabeth Bowen, and Orson Welles.

Autumn term seminar groups will study four of these eight set texts (chosen by the seminar leader). Spring term seminars are sign-up options: topics for this year will be finalised and announced in October. Lectures in the Spring term continue to explore aspects of modernism, and of ‘counter-modernism’, and introduce some of the drama and film of the period.

Examination is by means of a 3-hour written paper, or by Course Essay, if preferred and if no other Course Essay is being submitted by the candidate in that year.

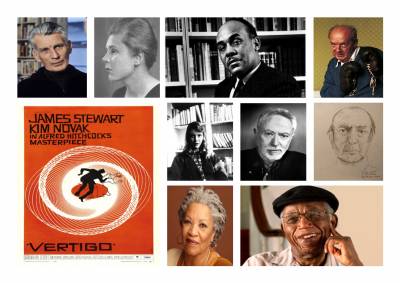

- Modern Literature II

This period is notable for the sheer volume and diversity of writing; no course can do it more than selective justice.

In the post-war period the experiments of ‘modernism’ have continued, in forms sometimes dubbed ‘postmodern’, in the work of such writers as Beckett, Nabokov, and Coetzee. Yet such categories do not satisfactorily cover the work of many other writers of considerable power and scope whose writing works in different ways. The course aims to give the student guidance in tracing some of the traditions taking shape or breaking down in the period. It seeks to provide the student with a critical and historical understanding of the most important literary tendencies, paying some attention to the relations between literature and other cultural forms (especially cinema) in a period of immense change.

Lectures establish the main terms of analysis and provide background knowledge, while a great variety of seminars concentrate on particular writers, movements, genres, or themes.

Lectures are offered on specified texts by set authors in various genres, including film, chosen to represent dominant strands of artistic production. There are introductory general lectures on these ‘set’ genres – these delineate crucial intellectual, historical, and artistic contexts – and lectures on other writers and issues essential to an understanding of the period.

Spring-term seminars cover areas of special interest. Recent topics have included: post-war fiction, the contemporary one-day novel, postmodern American fiction, beat writers, film and alienation, experimental writing, post-war thrillers, and motiveless evil in film and fiction.

Examination is by means of a three-hour written paper, or by Course Essay if preferred and if no other Course Essay is being submitted by the candidate in that year.

- Colonial and Postcolonial Literatures

This course aims to widen your knowledge of colonial and postcolonial literatures by engaging critically with Anglophone literature and its relation to the British Empire. You will be introduced to a range of postcolonial methods and approaches as tools for reading literary texts, across diverse genres and historical periods. Reading these works comparatively and contextually, you will analyse the complex relationships between imperialism and colonialism, racism and racialisation, and the globalisation of writing in English throughout the modern period.

The Autumn term will be taught through a combination of set text lectures and set text seminars. In the Autumn term each seminar leader runs an individually chosen programme of four seminars. The Spring term will be taught through a combination of lectures and options seminars

Students will have a choice between taking a three-hour written exam or writing an 8,000-word course essay, either of which will comprise 100 per cent of the summative assessment.

- Modern English Language

This course covers the major fields of the study of the English language, including grammar (how words and phrases are combined to form sentences), morphology (the study of the structure of words), lexicology and lexicography (the study of the meaning of words and how they are described in dictionaries), semantics (the study of meaning in language) and pragmatics (the study of language in use).

Aims:

· To teach students about the workings of language and communication, focusing on English.

· To teach students the fundamentals of English grammar, morphology, lexicology, lexicography, semantics and pragmatics.

Objectives:

At the end of the course students will have acquired a solid knowledge of the major concepts that play a role in the study of grammar, morphology, lexicology, lexicography, semantics and pragmatics, and will be able to analyse language from these perspectives using argumentation skills.

The course is useful for students contemplating a career in writing, journalism, publishing, or the teaching of English as a native or foreign language. It is taught over two terms in the form of weekly two-hour seminars based on a textbook and on handout materials.

As with other courses, students write one essay per term for this course; unlike other courses, Modern English Language tutorial essays are marked by one of the course seminar leaders, who then give the tutorial for that essay.

The course is examined by a three-hour written paper. (NB: it is not possible to be examined by Course Essay.)

- Literary Linguistics

This course foregrounds the relationship between language and literary and non-literary texts, and considers language use from particular perspectives. Students will be encouraged to think about the difference between written and spoken language in a detailed and systematic way, and to analyse different text types from a linguistic perspective, paying attention to grammatical, lexical and phonological features.

The first part of the course will introduce students to approaches from within stylistics and discourse analysis, and will examine the ways in which specific linguistic choices create variations in style and meaning. The questions of what makes a text, and what makes a text ‘cohesive’, will be explored, and the language associated with different discourse types such as politics, advertising and humour, will be examined. The course will go on to explore the way in which linguistic choices can be evaluated from different theoretical positions. Topics will include Critical Discourse Analysis, Raymond Williams’ Keywords, Marxist and feminist perspectives on language, and intertextuality.

The course will be taught in twenty two-hour seminars, and examined by an 8,000-word Course Essay.

(NB: it is not possible to be examined by a desk exam for this course.)

- History of the English Language

The course traces the growth of a standardised variety of English since the Anglo-Saxon period and considers how and why Standard English and other varieties have changed and continue to change. Classes will explore the social and cultural factors that have shaped English in different periods, and examine past and present attitudes to aspects of language (such as grammar, lexis, spelling and accent) and language change.

The structure of the course is broadly chronological. It will begin by considering the nature of different types of language change, and exploring the characteristic features of the language in the medieval, Early Modern and Late Modern periods. It will then trace the development of English from the Late Middle period to the present day, and examine the impact of events such as the Norman Conquest, the introduction of printing, and the spread of English around the world. Students will be strongly encouraged to think about the relationship between a language and its speakers, and to make connections between changing literary and linguistic conventions and preoccupations.

Among the topics studied are the ‘hows and whys’ of language change; the emerging awareness of regional and social dialect differences and of the need for grammars and dictionaries; the development of English lexicography from the sixteenth to the twenty-first centuries; Shakespeare’s language; and changes in the origin and meaning of English words.

Students will be taught by weekly two-hour seminars which will be a mixture of lectures and workshops.

Examination is by means of a 3-hour written paper, or by Course Essay, if preferred and if no other Course Essay is being submitted by the candidate in that year.

- Homosexuality and Queerness in Literary History

This course is taught in twenty two-hour seminars, and examined by an 8,000 word Course Essay. Enrolment will be limited to 30 students in all (approximately 15 from each year). The course is equally open to all students regardless of gender identification and sexual orientation.

The seminar format will probably vary from week to week, sometimes beginning with a lecture-type presentation, followed by a group discussion based on a particular literary work. For some meetings, students may be asked to give 5-10 minute presentations. Bibliographical information will be provided each week by seminar leaders.

Queer theory and transgender theory, along with gay and lesbian literary history, are an important part of the contemporary practice of literary criticism. This course aims to survey and introduce these fields, and to foster a critical understanding of their main tools of analysis and interpretation.

The course is partly historical, investigating different constructions of gender identification and same-sex attachment in different periods, and partly literary critical, considering and exemplifying various methods of interpretation of literary texts (including those associated with queer theory). The inquiry will be shaped by such questions as these: Should this subject be studied in a compartment of its own, or is it a neglected part of the subject we already study and teach? Why have queer and trans theories and gay and lesbian studies become so important in contemporary literary criticism? What are the main differences between these approaches? How and why has homosexuality been differently stigmatised at different cultural moments? How far have lesbianism and male homosexuality made common cause? What links homoeroticism and homophobia? What is the relation between minority sexuality and political power? How have issues around race been connected with those around sexuality and gender? What issues shape current ideas around gender fluidity and transgender identity?

The course will consider literature from classical times to the present day, probably including films, opera and drama. Male and female and non-binary authors will be studied, including many of the following: Ovid, Marlowe, Shakespeare, Wroth, Katherine Philips, Pope, Montagu, Byron, Whitman, Edward Lear, Michael Field, Wilde, Carpenter, Lawrence, Forster, Stein, Auden, Woolf, Hellman, Larsen, Langston Hughes, Ashon Crawley, Almodovar, Bechdel and Maggie Nelson.

(NB: it is not possible to be examined by desk examination for this course.)

There are also opportunities to take the following papers from outside the Department: Medieval French, Medieval German (all SELCS) and Early Medieval Archaeology of Britain (Archaeology).

Application Process

For information about what the department looks for in a strong UCAS application to our BA English programme and information about the assessment and interview process, please see our Application Process webpage.

Further Information

For further information about the UCL BA English programme, including questions about the application process, please email Natasha Clark

Close

Close